On Thursday evening I was in Philadelphia to speak at an event, sponsored by Carpenter’s Hall, commemorating the 250th anniversary of Jacob Duchés prayer on the third day of the Continental Congress. I was joined by the clergy of Philadelphia’s historic churches. They followed my opening historical remarks with a conversation about religion and public life.

Here is an edited version of my comments:

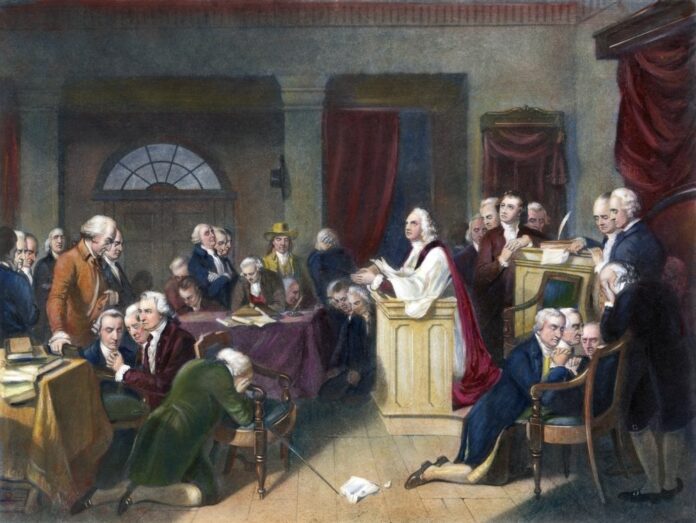

250 today, Reverend Jacob Duché, the Rector of Christ Church in Philadelphia, traveled a few blocks southwest to a brand new building that served primarily as the meeting place for the city’s carpenter’s guild.

Waiting for him there were representatives from twelve British colonies. They gathered at Carpenter’s Hall to respond to the Coercive Acts, a series of laws passed by Parliament to punish Bostonians for their participation in the destruction of 342 chests of East India tea in Boston Harbor the previous December. These acts closed the harbor to trade, empowered royal officials to restrict Massachusetts town meetings, eliminated the right to a trial by one’s peers, and demanded better accommodations for British soldiers stationed in the colonies.

Duché read several prayers that John Adams would later describe as part of “the established form.” Then Duché read Psalm 35. His choice of this text was not a random one. It was the Psalm designated for that day in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. After the scripture reading, Duché prayed extemporaneously for about ten minutes.

It almost didn’t happen.

On September 6, the second day of what would become known as the First Continental Congress, Thomas Cushing of Massachusetts moved that the group’s daily meeting be opened with prayer. Formal objections to Cushing’s proposal came from John Jay, one of the most devout and theological orthodox members in Carpenter’s Hall that day, and his fellow Anglican John Rutledge of South Carolina. These men argued that such a prayer, “as proper as the act would be,” would do more to divide the members of Congress than to unite them. Adams later described a room full of “some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Anabaptists, some Presbyterians and some Congregationalists.” How could they agree on the proper method of prayer? Would they be willing to listen to a prayer from a clergyman who did not share their denominational affiliation?

The problem was solved quickly when Boston’s Samuel Adams, a Congregationalist with a decidedly evangelical bent, supported Cushing’s motion, declaring, “I am no bigot. I can hear a prayer from a man of piety and virtue, who is at the same time a friend of his country.” He even suggested the right man for the job. “I am a stranger in Philadelphia,” Adams said, “but I have heard that Mr. Duché, an Episcopal clergyman, be desired to render prayers to the Congress tomorrow morning.” The motion passed. Duché was appointed the first chaplain of the Continental Congress.

By the time of this historic gathering, patriotic Protestant clergy had nearly a decade of experience interpreting the Bible in ways that supported the political agenda of their fellow Whigs. Duché was no exception. Psalm 35 was a perfect passage for the moment: “Plead my cause, O LORD, with them that strive with me; fight against them that fight against me. Take hold of shield and buckler, and stand up for mine help. Draw out also the spear, and stop the way against them that persecute me…” In the King James Version, the Psalm was titled “The Lord the Avenger of His People.”

No wonder John Adams, writing to his wife Abigail, noted “It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to be read on that morning.” Silas Deane, a representative from Connecticut, didn’t go as far as Adams with the providential musings, but could not ignore thinking about the scripture passage in light of the work of Congress. He claimed that Psalm 35 was “accidentally extremely Applicable.”

Duche’s prayer should be understood as an interpretation of Psalm 35 shaped by this revolutionary moment. “Look down in mercy, we beseech thee, upon these our American states who have fled to thee from the rod of the oppressor and thrown themselves upon thy gracious protection,” he prayed. He indirectly compared David asking God for protection from Saul in the book of 1 Samuel with Boston (and the other British colonies) asking God for protection from the tyrannical acts of the British Parliament. As historian Daniel Dreisbach has noted, “The psalmist’s prayer was the American’s prayer.” Duché’s God was on the side of the colonists. On September 7, 1774, the Anglican rector transformed Carpenter’s Hall into a temple of civil religion. The patriot cause was “righteous” and just. The British cause was “malicious,” “cruel,” and unrighteous.”

The Congregationalist John Adams told Abigail that he “had never heard a better Prayer, or one, so well pronounced, Epsicopalian as [Duché] is.” He added that even his own pastor, Dr. Samuel Cooper of Brattle Street Church in Boston, “never prayed with such fervor, such Ardor, such Earnestness and Pathos, and in Language so elegant and sublime–for America, for Congress, for The Province of Massachusetts Bay, and especially the Town of Boston.” That was high praise from the son of Puritans. Silas Deane, a representative from Connecticut, praised Duché’s eloquence. The prayer, he said, was “worth riding One Hundred Miles to hear…Even Quakers shed Tears.”

If Duché did pray for ten minutes, as Deane claimed, the prayer that we have today was probably just a small part of what Duché said. Some members of the Continental Congress wanted to publish the prayer. This assumes that Duché either had a text, or someone in the room was writing-down every word as the clergyman spoke. The Congress decided not to publish the full prayer–whatever it consisted of– in order to protect Duché from British officials and soldiers who might not take too highly to such an overtly patriotic supplication.

Two postscripts are in order as we reflect on the 250th anniversary of Duché’s prayer.

First, Duché did not remain a patriot for long. Though he was willing to pray at the First Continental Congress, he never fully supported American independence. He viewed the patriots, especially those in his home state of Pennsylvania, as too radical. From his post at Christ Church, Duché saw newly elected backcountry Presbyterians regularly and violently attack Tories and political moderates. These men, who Duché did not believe were smart enough to hold office in the Pennsylvania State House, drew-up a state constitution that opened-up the voting rolls to non-landholding men, including free Blacks.

All of this was too much for the moderate Anglican pastor with a reputation for building bridges between those with religious and political differences. In 1777, well after his stint as chaplain to Congress had ended, he expressed some of his concerns about American independence in a letter to George Washington. The general was appalled by Duché’s lack of patriotism and shared the letter with the Continental Congress. When the letter became public, Duché’s career in America was over. Shortly thereafter he left for England as yet another Anglican clergyman forced to flee the British colonies amid a revolutionary climate that placed them in physical danger. He would remain there for the next fifteen years.

Second, Duché’s prayer provides a usable past for the Christian Right. Writers such as David Barton and others are quick to note that the first major meeting of American patriots opened with prayer. As a result, America must have been founded as a Christian nation.

Read it all at Current