PR car-crashes for the Church of England are like buses—there are none for ages, then three come along at once. Except for the Church of England, the ‘there are none for ages’ bit isn’t true.

Following the constant stream of negative publicity about the sexuality debates, we then had two reports on safeguarding, Wilkinson and Jay, with the latter simply setting us up to fail. Instead of being asked to look at options for independent safeguarding practice, and independent safeguarding scrutiny, Professor Jay was briefed to look only at the option of fully independent safeguarding practice, despite the fact that experts in this field think that is a very bad idea. So either we follow her recommendations and do something stupid, or we do something sensible and get accused of defying the recommendations of the report.

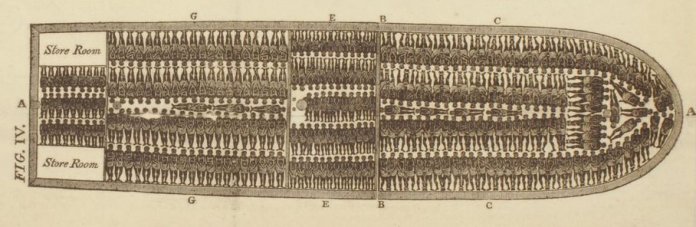

Something similar has now happened on the question of race and slavery reparations. The Church Commissioners wanted to investigate any past dependance on and profit from the transatlantic slave movements, and found that its predecessor, the Queen Anne’s Bounty, had profited from investment in the South Sea Company which was involved in the transport of 34,000 slaves out of the approximately 12.5 million transported on about 35,000 transatlantic voyages. Its involvement in the slave trade ran from 1715 to 1739—a total of 24 years. It has been estimated that the profit to the Bounty amounted to around 3%, though subsequently its main sources of income were elsewhere until it was taken up into the Church Commissioners which were established in 1948.

But you wouldn’t know any of that from the report of the Oversight Group that the Commissioners set up to advise on the use of a £100m investment fund that had already committed to. Reading the report, you would get the impression that the historical chattel slave trade was the cause of all the world’s racist ills, and that the Church of England was responsible for all of this.

The reasons for this are multifold, but they begin with the ignorance and distortion of both historic and present facts around the issue. The report claims:

African chattel enslavement was central to the growth of the British economy of the 18th and 19th centuries and the nation’s wealth thereafter (p 5).

But this is not true. As Niall Gooch points out:

The typical discourse around these kind of proposals is endlessly frustrating. For example, it is often stated explicitly or assumed implicitly that British national prosperity was “built on slavery”. This is flatly untrue: Britain was a wealthy country well before the transatlantic slave trade and continued to be one long after we had entirely banned slavery throughout the Empire, at no small cost to ourselves. Even at its height, slavery was a relatively small component of the British economy. The economic power that underpinned our time as global hegemon was largely the result not of dark deeds or plunder, but of our innovative, free and dynamic economy and political stability.

But there is an ironic twist to this: the wealth that came from the innovation of the industrial revolution came from the mining of coal and iron ore, gruelling work conducted by white working men, a group the Church of England continues to struggle to engage with. There are no quotas in place to measure the involvement of this racial group.

And the report fails to make any mention of the fact that slavery was a routine practice of tribal conflict within Africa itself, and was likely introduced into Europe through the slavery practices of Islam. All this can be found in any primer on slavery, such as Jeremy Black’s Slavery: a new global history.

Whereas the prime European demand in the Americas was for male labour… in the case of these other trades[in the Islamic world] the demand was primarily for women, particularly as domestic servants and sex slaves. This was because there were few equivalents in the Islamic world to the large labour-hungry plantation economy of the European New World…Lack of sources makes it harder to estimate the number of Africans traded across the Sahara, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean than across the Atlantic, but it was probably as many—and indeed there are suggestions that it was greater (pp 54–55).

And, on the other side of the historical argument, the report makes no mention of the significant rolethe Church of England had in the opposition to and abolition of the slave trade:

The Church’s report and summary make no reference to Christians’ admirable central role in the suppression and abolition of slavery. Anglicans (in addition to Quakers) were at the forefront of the abolition movement from the 1780s, all their bishops voted en bloc in favour when the abolition legislation was brought before parliament, and the Church spent considerable time, effort and expense for many years thereafter in suppressing the slave trade elsewhere.

The distortion of facts extends to the present, where it is claimed that Black Caribbeans are uniquely disadvantaged economically because of the structural racism in British society due to the legacy of the slave trade. But the very same ONS data points out that, in terms of the performance in education by racial group, at the top are Chinese, Asians, and then Black Africans, and at the bottom of the performance are Black Caribbeans and white working class—and in all groups boys perform worse than girls. (The chart on the right does not separate Black Africans from Black Caribbeans but does note the wide difference in other charts and in the narrative further up.) It is clear that the main factor here is not race; those groups performing well have cultures that value discipline and hard work and have an emphasis on family stability and marital commitment.

Read it all at Psephizo