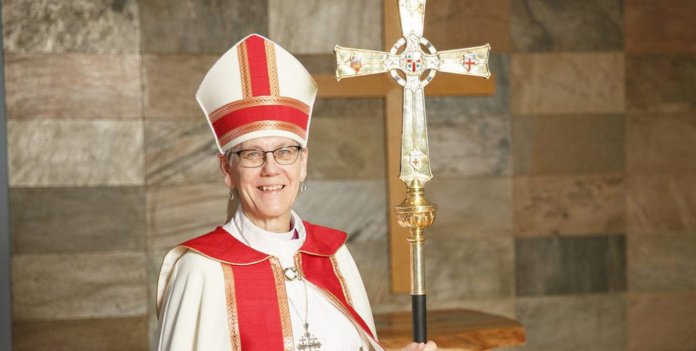

The Most Rev. Linda Nicholls, Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada preached the following homily at the New Year’s Day Festal Eucharist at Christ Church Cathedral in Ottawa.

Sometimes, we stand on the cusp of the new year with anticipation and excitement as we look ahead to opportunities and adventures. At other times, we come to the new year weighed down by grief, anxiety or fears of what lies ahead—as we leave a year of struggles. 2023 into 2024 feels more like the latter.

We began 2023 in hopes that COVID was waning and life began to turn into a renewed routine of in-person meetings and gatherings. Planning for events could resume as we continued mass vaccination programs. Yet at the end of the year COVID lingers still and—though seemingly less severe for many people—still disrupts plans and leaves long-term effects for some.

We experienced another year where climate change has led to severe weather events—including another summer of forest fires that took the lives of at least three firefighters in Canada, ravaged vast swaths of Canadian forests and seems now to be normal each summer.

Mass shootings—especially in the USA—happen so frequently now that they are just part of a normal news pattern each month. They hardly catch our attention.

Earthquakes rumble around the world—including the devastation in Turkey and Syria.

Wars continue unabated. Ukraine continues its resistance of Russia. A mass invasion of Armenia was conducted by Azerbaijan in September. And the horrific violence of October 7 in Israel by Hamas and the continuing war with Hamas that has killed at least 21,000 Gazan citizens, including at least 6,000 children. Haiti has descended into a lawlessness no one seems able to control.

Are we not supposed to be civilized nations who have learned from the past? After WWII, we established the United Nations to work with other countries to establish commitments to human rights, to justice, to fair treatment and limits on the waging of war. Yet those commitments are only as strong as the willingness to be subject to them.

In high school, one of the books on the curriculum was Lord of the Flies, a controversial exploration of what happens to a group of school boys stranded on an island as they seek to survive. Social order crumbles under the fears and anxieties as they struggle to balance the needs of the group, especially those to perceived to be weak, with their personal desires—and violence and death follow. Human nature has a core predilection for self-preservation at all costs that allows evil to break through and thrive.

Look around—and we see it wherever there are inequities, injustices, fear, oppression and suffering flourishing. So looking into 2024 is a challenge—will wiping out Hamas create stability and security for Israel? Will the grief of Gazans remain peaceful in the future? Will the war in Ukraine find an ending that does not lead to more conflict? Is peace possible?

You may say—what does this have to do with Canada? We live in relative safety and security. Can’t we just blinker ourselves from the suffering elsewhere? We could, but we do not live in isolation. Once, communications around the globe would take weeks and months by snail mail on ships so that responses were slow and conflicts contained. Now we live in a global community where a small event in one part of the world is known instantly and ripples through economic and social relationships. The price of oil fluctuates with the emergence of a war on the other side of the globe. The delivery of grain and other foods is disrupted as ships must find new routes. Food costs rise sharply due to supply chain and delivery issues—and we are all affected.

Swirling patterns of immigration and refugee migration bring tensions, and the hatreds of local conflicts flow into the midst of every nation. Just look at the rise of antisemitism and Islamophobia in cities across Canada in recent months due to the Israel-Gaza war.

What happens to our neighbours—wherever they are in this world—happens to us. Ernest Hemingway poignantly declared “Ask not for whom the bell tolls—it tolls for thee.”

The weight of the darkness in our world seems stronger this year. Maybe more so because we believe that human beings are both called and capable of living differently.

As a Christian community we know this is true—despite all that we may see. We have seen and experienced a love stronger than pain and suffering that opens a path through repentance and forgiveness to new life. We live by a faith rooted in an understanding of being human in relationship with God that offers another way.

To some it seems like a naïve way—even simplistic—yet it is rooted in a wisdom stronger than death. It begins in the love of the Creator for all humankind in its fullness. We were created with the capacity for love, commitment and community, with the gift of freedom to choose that also gives us the capacity for selfishness, greed, jealousy, and anger. God’s love is both tender and firm—inviting us to live as the beloved—inviting us into loving one another as ourselves—and offering a never-failing gift of forgiveness and renewal. This love is not naïve about human nature, for God faced the depth of human capacity for cruelty in the death of Jesus—and “did not strike back but overcame hatred with love” (to quote one of our eucharistic prayers). God offers us a path through the darkness of human betrayal and sin—our own and others’—and offers life again and again and again.

That is how we face a new year. Not in denial of the pain and suffering—but in the knowledge that even the deepest darkness of human evil cannot overcome the love of God.

I have watched with horror the unfolding violence in the Holy Land in places I had visited twice in the past year, including the bombing of the Al Ahli Anglican hospital, the utter decimation of Gaza and contemplated the bottomless pit of grief for the Jewish community on October 7, reopening the wounds of centuries of antisemitism. I have also heard the calls of Christian leaders in the land of the Holy One and around the world crying out for an end to the violence and have seen the witness of Christians in the Holy Land—longing for another way. The Rev. Dr. Richard Sewell spoke to the House of Bishops and to your Synod here in Ottawa in October and Archbishop Hosam joined the other patriarchs and religious leaders in calling for peace. “As custodians of the Christian faith, deeply rooted in the Holy Land, we stand in solidarity with the people of this region, who are enduring the devastating consequences of continued strife. Our faith, which is founded on the teachings of Jesus Christ, compels us to advocate for the cessation of all violent and military activities that bring harm to both Palestinian and Israeli civilians.”

The promise of the birth of Jesus is that God comes into the midst of all that is wrong, where people cannot live freely and fully in relationship with God due to the power of evil, and comes in the smallest of ways, in the helplessness of a baby! He comes as a sign that Simeon and Anna will recognize in the Temple, shepherds and magi will acknowledge, and he will change the world, not by overthrowing one power with another, but by subverting it with love that offers hope, that lifts up the lowly, feeds the poor, heals the sick and visits those in prison. By small gestures of human kindness and sacrifice, Jesus and all who follow him give the world signs that another way is possible.

That is what gives me hope. I look around and ask, Where do I see the work of Christ? Where do I see signs of hope in the midst of the pain and sorrow and fears?

One of the gifts of being the primate has been to travel across Canada and the world to see how Anglicans are bringing that hope.

In this year alone I visited projects in Kenya where PWRDF assists in building shallow wells in a drought-stricken region that give those nearby cleaner water for their farms, animals and homes; provides a donkey to a widow so the 3 km trek for water allows her to bring 5 jerry cans back instead of one at a time; supports training and microloans for small dairy farmers to build a better cow shack or storage barn, increase milk production and allows children to go to school because they have the fees to do so.

I visited Yukon & Caledonia dioceses and met lay Anglicans sustaining worship and outreach through food banks, soup kitchens and community ministries and travelled with their bishops who drive long distances to visit, teach, preach and offer the sacraments.

I visited Labrador and Rigolet and saw the joy of ministry in those in isolated areas—and locally raised up clergy serving their community and supporting a women’s shelter.

I visited the Diocese of Amazonia, Brazil where a very, very small group of clergy in a vast area of the Amazon offer worship and reach out to young people and families in their neighbourhoods through music programs for youth and adults, jujitsu to develop confidence and leadership, tutoring for children with special needs, and support for Indigenous women in the city; and always with joyous worship alongside the advocacy of their leadership for environmental issues, climate change challenges, and Indigenous rights.

I visited the parishes of lay people being given the Canadian Anglican Award of Merit—in Arundel, Quebec, in Beamsville, Ontario, in Vancouver, B.C. and next month in Montreal, Quebec. Lay people who are all surprised to be honoured because they were simply living into their baptismal calling with the gifts they have—yet each of them an inspiration to their fellow parishioners and the Church.

I celebrated those honoured by the Archbishop of Canterbury with Lambeth Awards at a special evensong in Cobourga few weeks ago. Clergy and laity who have offered extraordinary service to the Anglican Communion in the areas of music, evangelism, service, ecumenism and community life. Again, surprised to be honoured for simply faithfully living their calling as a sign of what we are all called to do and be.

None of these are world-shattering efforts—they are small, faithful efforts to live into the name of Jesus. They will not stop the war in Israel & Gaza or Ukraine—they will not end climate change—they will light hope for those they serve and lead. They are my inspiration to do the same and not lose sight of the power of planting seeds and caring.

When we are young, with hubris and idealism, we believe we can change the world and fix the mistakes of our forbears. As we age, disillusionment sets in as the realities of human sinfulness and the intransigence of systems stronger than we are break our optimism. Through it all the gospel whispers its voice of invitation. The Spirit whispers, “You are not the saviour but you are called to bring what you can in this moment of time and place with your gifts and opportunities before you,”—and that is enough.

So as we enter this new year of 2024, feeling the weight of the sorrows and pain of the world, the endlessness of war and the fears for our planet, let us hold firm to the hope of the gospel with faith and trust God’s infinite love and mercy and—like Mary—respond with a continuing ‘yes’ to God’s call.

Let me conclude with the blessing heard in the Hebrew scripture for today—a blessing given to the Israelites as they continued their journey. It embodies the promise that God is with us in whatever lies ahead. It is my prayer for you and for the whole of the Anglican Church of Canada as we enter this new year and seek to live as we have been called.

The Lord bless you and keep you;

The Lord make His face shine upon you,

And be gracious to you;

The Lord lift up His countenance upon you,

And give you peace.