Building on my earlier reading of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s contributions about Communion life, this article explores the ecclesiological questions that are important, and currently intertwined with, the questions relating to sexuality that tend to dominate discussion.

It argues that although all wish for unity and communion there are currently two main competing visions of the end of communion in terms of its goal or purpose:

- the traditional vision of Communion Catholicity which is an ecumenically shared vision;

- and a vision of Autonomous Inclusivism where provincial autonomy is central.

The account of the Communion offered to the Conference by the Archbishop does not articulate that of Communion Catholicity and appears perilously close to that of Autonomous Inclusivism. If this is now the end (in sense of destiny and goal) it would entail the end (in sense of destruction) of the Communion as it has developed and understood itself because it embraces provincially driven pluralism while sidelining or abandoning the quest to be of one mind which I argue is part of the biblical calling of the church.

By contrast, the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches (GSFA) are firmly committed to Communion Catholicity as well as to traditional teaching on sexuality. The question is whether the Archbishop of Canterbury and IASCUFO can now work with the Global South to enable the current Instruments to be “reset” and return to seeking the historic goal of “Communion Catholicity” or whether we are seeing the end of the Communion as we have known it.

In my previous article I tried to examine what the Archbishop of Canterbury was saying in his letter and speech of Tuesday. I did so in relation to both sexuality as regards the status of Lambeth I.10 and the reality of the Communion’s life. I argued that while there was much of value there were also important areas which lacked clarity. Above all, there was an ecclesiological deficit in each area leaving us with key questions—“what bearing, if any, does the continued “validity” of I.10 have on the ordering of the life of the Communion?” and “is the reality of “a plurality of views” in the Communion no longer the ecclesiological problem it has been in the past and if so what does that mean for our working ecclesiology as a communion and in our ecumenical relationships?”

This latter ecclesiological question is one which, “given Anglican polity, and especially the autonomy of Provinces” (Call on Human Dignity, 2.3, p.15) has hung over the Communion for decades and which Archbishop Robert Runcie clearly set out back at the 1988 Conference:

“There are real and serious threats to our unity and communion…The problem that confronts us as Anglicans arises..from the relationship of independent provinces with each other…The New Testament surely speaks more in terms of interdependence than independence…Are we being called though events and theological interpretation to move from independence to interdependence…Let me put it in starkly simple terms: do we really want unity within the Anglican Communion? Is our worldwide family of Christians worth bonding together? Or is our paramount concern the preservation or promotion of that particular expression of Anglicanism which has developed within the culture of our own province?…I believe we still need the Anglican Communion but we have reached the stage in the growth of the Communion when we must begin to make radical choices, or growth will imperceptibly turn to decay. I believe the choice between independence and interdependence, already set before us as a Communion in embryo twenty-five years ago, is quite simply the choice between unity or gradual fragmentation… (The Truth Shall Make You Free, pp. 14-17).”

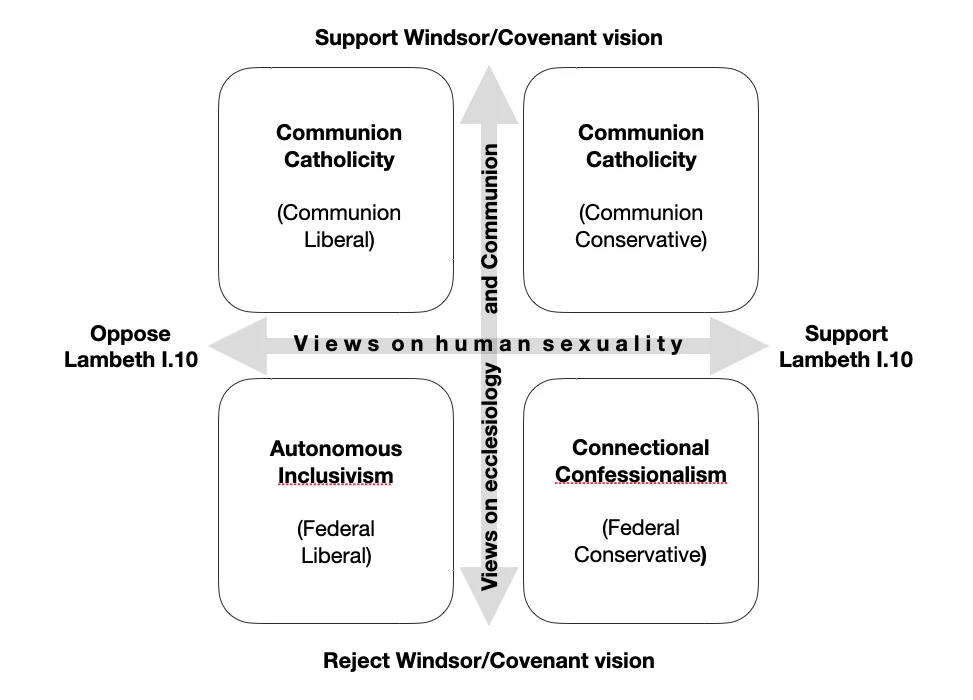

In its current manifestation this challenge brings us back, again, to the question of how different teachings in relation to marriage and sexuality are related to different ecclesiological visions. As I set out in an article earlier in the Conference (drawing on two of my previous and fuller discussions and also two pieces in 2006 and 2008 by Graham Kings) this has been a constant and divisive question since at least The Windsor Report. One way of seeking to understand it is by representing different viewpoints on a quadrant created by axes mapping a spectrum of views on sexuality (the x-axis in relation to I.10) and on ecclesiology (the y-axis relating to support or rejection of the Windsor/Covenant vision of life in communion).

The Windsor/Covenant vision in the upper half of the y-axis is one of “Communion Catholicity”. This can be held by both those supporting I.10 (the Communion Conservative version at top right) and those—most famously Archbishop Rowan Williams—who though not convinced by the claims of I.10 (and so on the left-hand side of the horizontal axis) respect it as the teaching of the Church (the Communion Liberal version at top left). In relation to the life of the Communion this “Communion Catholicity” vision of autonomy-in-communion, freedom held within interdependence and mutual accountability, leads to the sort of position summed up in the words of Archbishop Rowan Williams which I quoted in my previous article and contrasted with those of Archbishop Justin Welby who has at this Conference only affirmed the first of Archbishop Rowan’s three statements on his appointment in 2002:

“[1] The Lambeth resolution of 1998 declares clearly what is the mind of the overwhelming majority in the Communion, and [2] what the Communion will and will not approve or authorise. I accept that [3] any individual diocese or even province that officially overturns or repudiates this resolution poses a substantial problem for the sacramental unity of the Communion.”

In contrast to this view are two alternative ecclesiologies which in the crisis of recent years have sought justification in expounding as authentically Anglican the privileging of individual provincial autonomy over the mind of the Communion and wider church.

The most obvious form of this is seen in those opposed to I.10, especially in the US, who have overturned and repudiated it and then ignored the pleas of the Communion to turn back from this course. They are represented at the bottom left and have an ecclesiology which holds that each province’s autonomy means that it determines its own actions within its own jurisdiction as it sees best and that other Anglican provinces and the Communion Instruments should honour and respect those decisions. Even after unilateral action against the mind of Communion a province should therefore continue to be fully included in Communion life and other provinces should maintain bonds of communion with them despite them having created significant disagreements and sought to establish plurality on matters of doctrine, liturgy, sacramental order, morals, practice and discipline. This perspective can thus be described as “autonomous inclusivism” and results in a vision of “communion” that embraces plurality and prioritises the province over the global body. Extra-provincial relationships are here more that of a voluntary association or federation of autonomous churches each free to disregard the mind of the wider fellowship (hence “federal liberal”) rather than the self-understanding of the Anglican Communion as classically understood and the vision of “visible unity” it has pursued ecumenically.

Although less clearly defined, there are elements of a conservative alternative vision (bottom right) in at least some of those provinces which intervened in the US and consecrated bishops to serve there and who are part of GAFCON and have been strongly separatist in relation to the current Instruments. This appears to take the form of a purely confessional stance whose vision of the church is one which draws together those who can agree on, for example, the Jerusalem Declaration. What is not clear is whether this represents a fundamental rejection of, and alternative to, the richer Windsor/Covenant ecclesial vision. It may do so or it may simply be an emergency remedial measure in the light of the failure of the Windsor/Covenant vision within the current Instruments. In the latter scenario, its current advocates might willingly embrace a form of Communion Catholicity such as the covenantal structure being developed by the Global South.

What is the End of (the) Communion?

One way of exploring these differences is in terms of their different views of the end—the goal, or purpose—of ecclesial communion and thus of the Anglican Communion. Any account of this end of ecclesial communion must, in turn, flow from our account of humanity’s ultimate end of communion in truth and love with the triune God which is graciously given and revealed to us in Christ and the Spirit-inspired apostolic witness to Christ. That is why the disturbing “declaration” in the Call on Reconciliation (2.1, p.11) that “We believe in God who is both three and one, who holds difference and unity in the heart of God’s being, as Father, Son and Holy Spirit” (italics added) may prove to be so significant and reveal the depth of the disagreements.

Among Anglicans today the two main competing perspectives are those of Communion Catholicity (Quadrants II and III) and Autonomous Inclusivism (Quadrant IV). We here face, among ourselves as Anglicans, the pressing questions which Cardinal Koch’s address to the Lambeth Conference identified in relation to ecumenism and Christian unity more widely:

“That brings the main difficulty of the present ecumenical situation to light. On the one hand, it was possible in previous phases of the ecumenical movement to reach an extensive and pleasing consensus on many hitherto controversial individual questions around the understanding of faith and the theological structure of the church. On the other hand, most of the still existing points of difference continue to make themselves felt in the differing understanding of the ecumenical unity of the church. In this double context, I perceive the most elementary challenge in the ecumenical situation today as being what the late bishop of Würzburg and eminent ecumenist Paul-Werner Scheele diagnosed as follows: “Regarding unity, we agree that we want unity but not on what kind.”

Amongst ourselves as Anglicans we might say this is being expressed as “Regarding communion, we agree that we want communion but not on what kind”.

The previous clear consensus, developed over decades, was one where the end or goal was that of Communion Catholicity but we are now possibly leaving this behind. We could be turning away from this to make our end or goal what the cardinal identified as an approach in which “churches and ecclesial communities…strongly promote diversity and difference” and visible unity “merely consists largely in the sum of all available church realities”.

This relates to what he refers to as “another great challenge…the pluralist and relativist Zeitgeist” in which “there is no thinking backwards from the plurality of reality, and we must not do so if we don’t want to expose ourselves to the suspicion of a totalitarian approach” (one cannot help but hear in this echoes of some of the, to my mind unfair, criticisms of the proposed Anglican Covenant). From such a postmodern perspective, the cardinal continued,

“plurality is said to be the only way to reflect the whole of reality, as far as this is possible at all. It is therefore characteristic of postmodernism to abandon unitary thinking on principle, which means not only tolerating and accepting pluralism but fundamentally opting for it…people have not only learned to live with the historical and present pluralism but also basically welcome it, so that the ecumenical search for a way to restore church unity appears unrealistic and is regarded as undesirable.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s

- portrait of the state of the Communion at the Conference and its failure to even mention mutuality, accountability or interdependence,

- consistent failure over time to re-articulate and commend the Windsor and Covenant vision of Communion Catholicity or to protest against the unilateral actions of those committed to autonomous inclusivism, and

- unexpanded and unqualified statement that “We have a plurality of views”

are all signs pointing in one direction, one in which:

- the fact of a plurality of contradictory views and practices concerning the Communion’s teaching as to Scripture’s witness concerning marriage and sexual behaviour is not ultimately incompatible with life in communion;

- we can only speak of “majority” and “minority” perspectives existing within the Communion at any point in time and not, in any meaningful way, of the Communion approving or authorising anything, only of provinces doing so;

- unilateral actions against the mind of the Communion have no consequences in the ordering of Communion life;

- it is wrong to hold that the “deep differences that exist within the Communion over same-sex marriage and human sexuality” (Letter) should be seen as impairing communion; and

- it is wrong to believe, in relation to I.10, that “any individual diocese or even province that officially overturns or repudiates this resolution poses a substantial problem for the sacramental unity of the Communion”.

By default, even if not by intention, and however the Archbishop might personally wish to locate himself in the quadrant, this approach is one which positions the Communion in a place which looks perilously close to the autonomous inclusivism vision.

What needs to be acknowledged, however, is that if the Anglican understanding of the end (ie goal) of communion is indeed now this pluralist vision rooted in a favouring of autonomous inclusivism then it marks the end (in the sense of termination and destruction) of the Communion as it has existed until now where it has been shaped by the end/goal of Communion Catholicity.

The Call to be of One Mind

Faced with the undeniable reality that “we have a plurality of views” (on both sexuality and the end/goal of communion) how should we interpret and respond to this given New Testament appeals and prayers such as these?:

“Therefore, if you have any encouragement from being united with Christ, if any comfort from his love, if any common sharing in the Spirit, if any tenderness and compassion, then make my joy complete by being like-minded, having the same love, being one in spirit and of one mind (Phil 2:1-2).

I plead with Euodia and I plead with Syntyche to be of the same mind in the Lord (Philippians 4:2).

May the God who gives endurance and encouragement give you the same attitude of mind toward each other that Christ Jesus had, so that with one mind and one voice you may glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. (Romans 15:5-6)

Strive for full restoration, encourage one another, be of one mind, live in peace. And the God of love and peace will be with you (2 Cor 13:11).”

In the light of these and other parts of Scripture, and “if unity with apostolic teaching and apostolic witness is a natural consequence of understanding unity as unity in Christ”, then the calling of the church is not to accept this plurality and embrace it within our vision of the goal of life in communion. Our calling is rather to lament it, to recognise it as a sign that we are being disobedient and failing to live the communion into which we are called in Christ, and to commit ourselves afresh to seeking the unity of God’s people in Christ we find in Scripture.

What James writes about double-mindedness in the individual Christian applies also to double-mindedness within the church. A church or communion of churches which simply accepts such double-mindedness on a matter relating to the pattern of holy living called for among Christ’s disciples where it itself holds that Scripture teaches something will inevitably be “unstable in all they do” (James 1:8). Similarly, a communion of churches which accepts double-mindedness about what it means to be a communion of churches and the goal of communion will also inevitably be unstable. Such instability leads not to walking together as we should be doing but—as we have seen in recent years and also in aspects of this Conference—to the instability of which James writes which is more like the walking of a drunkard or Archbishop Runcie’s “gradual fragmentation”. When we find ourselves as a Communion in this state a word repeated three times in 1 Peter which is being studied in the Conference is apposite: “with minds that are alert and fully sober, set your hope on the grace to be brought to you when Jesus Christ is revealed at his coming…be alert and of sober mind so that you may pray…Be alert and of sober mind. Your enemy the devil prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour” (1 Peter 1:13, 4:7, 5:8).

The Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches (GSFA)

As has been evident for some time and is reaffirmed in their communiqué as the Lambeth Conference closes, the GSFA are clearly positioned as committed to both Lambeth I.10 and the vision of life in communion set out in Windsor and The Covenant. They are now the primary advocates of Communion Catholicity within the life of the Communion and are clear that there is an “unattended ‘ecclesial deficit’ in the Communion” (6.6). Within the quadrant they are squarely in the top-right corner (II) but one of the problems is that most of those who previously may have been Communion Catholicity allies in the top-left corner (III) have moved to join TEC and embrace autonomous inclusivism (IV).

The GSFA believe that “Anglican identity is neither sociological nor historical. It is first and foremost doctrinal” (5.6) and that

“If Anglican identity and unity are rooted in common doctrine, then we cannot be a Communion with a plurality of beliefs. There need to be limits to theological diversity, limits that are set by a plain and canonical reading of Scripture and which is supported by church history (5.7).”

They are also deeply concerned that “it would seem that the global Anglican Communion falls short of being a truly interdependent Communion of Churches; it is becoming an association, or at best a federation, of autonomous Provinces” (6.7(b)). As argued above, they believe that

“The hard reality is that we cannot be a true Communion if some Provinces insist on their own autonomy and disregard the necessity of being an interdependent, ecclesial body (6.7(d)).”

Their response to this has two main elements. On the one hand, they are developing their own structures shaped by the goal of communion expressed in Communion Catholicity:

“We will find ways to be mutually accountable to one another as orthodox Provinces in staying true to the Word of God. We want to express enhanced ecclesial responsibility as a global body of faithful Anglican Provinces and dioceses. With common doctrine on essentials and mutual accountability, we anticipate more synergy and joy in living out our faith and being Christ’s witnesses to a watching world that is lost and grappling with pain and hopelessness (6.5)

Several orthodox Global South Provinces…have started to voluntarily bond themselves together on the basis of common doctrine to be accountable to one another in faith, order and morals and to express their ‘koinonia’ (fellowship) through relational networks of discipleship, evangelism, mission, economic empowerment and community services. The form in which this is taking place is the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches (GSFA). This is an ecclesial body within the Communion that, while being rooted in the Global South Provinces, is now a world-wide Anglican Fellowship based on commitment to doctrine and a Covenantal Structure (The Cairo Covenant, adopted in 2019 and updated in 2021) (6.6)”

On the other hand, they will continue to engage with the wider Anglican Communion structures but with the conviction that

“Biblical faithfulness and relational integrity now require us as orthodox Bishops to speak of ‘degrees of communion’ with other Provinces, recognising the extent to which those degrees may increase and intensify or decrease and face temporary or permanent impairment. Simply stated, we find that if there is no authentic repentance by the revisionist Provinces, then we will sadly accept a state of ‘impaired communion’ with them. (6.7(f))”

In relation to the traditional Instruments they will

“continue to connect with the Communion Instruments as best we can without compromising our convictions about the authority and orthodox reading of Holy Scripture. The current situation warrants us to adopt suitable forms of ‘visible differentiation’. We will seek not to be schismatic. (6.7(j)).”

In doing so they will work for “a resetting process” with proposals for “the repair of the tear in the Anglican Communion” (6.7(k)).

The GSFA will also, although they do not particularly draw attention to this, thereby be contributing to the Communion’s ecumenical calling by heeding the warnings that have been given to previous Lambeth Conferences by ecumenical guests from Rome such as a homily at the 1998 Conference (before it passed I.10) by Cardinal Cassidy, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (PCPCU) and the address by his successor Cardinal Kasper at the 2008 Conference. Cardinal Cassidy quoted the Virginia Report, presented to the 1998 Conference, as he described one “insidious” threat to unity in these terms:

“It comes when prayer for unity and ecumenical engagement are compartmentalised, hermetically sealed off from other areas of Church life and decision-making. If these are just part of a series of concerns, perhaps left to the enthusiasts, the ecumenical imperative becomes subtly marginalised. Different approaches, important decisions, in other areas of the Church’s life can conflict with it and may even undermine it. The commitment to unity is relativised if diversity and differences that cannot be reconciled with the Gospel are at the same time being embraced and exalted. It is put in question when pluralism in the Church comes to be regarded as a kind of ‘postmodern’ beatitude. It will be lost sight of altogether if radical obedience, and the necessity of costly ethical choices for faithful discipleship, are swept aside by a naive overemphasis on our innate goodness, underestimating the reality of sin in our lives and our world and also the power of Christ’s redemption and the grace-filled possibility of conversion. Are we not experiencing in fact new and deep divisions among Christians as a result of contrasting approaches to human sexuality for instance? When such attitudes are in the ascendant, disunity between Christians will remain unresolved.…The Virginia Report is surely right to argue that, ‘At all times the theological praxis of the local church must be consistent with the truth of the gospel which belongs to the universal Church’; and that the universal Church sometimes has ‘to say with firmness that a particular local practice or theory is incompatible with Christian faith’.”

The End of (the) Communion?

Read it all in Psephizo