Reparations have a troubled history, and rightly. The word itself, in its familiar sense, seems to have been a euphemism thought up by lawyers after the first world war. President Woodrow Wilson had promised a peace ‘without indemnities’. So no indemnities: ‘reparations’ instead. It sounded less objectionable. It was further agreed that liability should cover only demonstrable damage, not be punishment for the act of war itself – a remarkable and perhaps unprecedented concession by the victors to the vanquished (who had themselves recently imposed heavy indemnities on Russia, and before that on France). Yet reparations – relatively modest in total and largely unpaid – still became probably the most divisive and damaging aspect of the post-war Treaty of Versailles. The many groups advocating various forms of reparations today would be well-advised to show some circumspection.

The case for reparations at the time was politically irresistible and ethically defensible. Germany had not only invaded its neighbours, it had fought the whole war on their territories. Their populations had been subject to forced labour. Industries had been looted, with machinery removed lock, stock and barrel. Housing and infrastructure had been destroyed by four years of devastating combat – and in retreating, German armies had carried out a scorched-earth policy, which included flooding coal mines and destroying crops. Millions were left widowed, orphaned or disabled, needing pensions.

Finally, reparations were partly conceived as a deterrent to future aggression if voters and taxpayers realised they might be liable to pay compensation for their country’s misdeeds. As an Allied statement put it: ‘Somebody must suffer the consequences of the war. Is it to be Germany, or only the peoples she has wronged?’ So the case for reparations seemed strong and coherent to both politicians and peoples as the Great War ended.

The contrast with demands for reparations today is glaring. Then, the damage was visible, recent and quantifiable. The victims were readily identifiable and were in dire and urgent need. There was little doubt, at least in the minds of the Allies, as to who was principally responsible: Germany, its rulers and to some degree its people. Nevertheless, reparations caused bitter controversy, which perhaps even a century later is not entirely extinct. The Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes led criticism of what he called ‘imbecile greed’ and ‘hypocrisy’.

This was somewhat unfair, but nevertheless there were objections in principle to reparations that later generations have rightly taken seriously. Reparations caused endless, dangerous resentment, and damaged the prospects of genuine reconciliation. They arguably harmed both those paying them and those receiving them. They caused severe trade distortions and added to financial instability. They imposed burdens on people not responsible for the damage being repaired. Worst of all, the political outcomes were disastrous.

One might think that such a discouraging and well-known historical example as the Treaty of Versailles would cause those blithely proposing billions or trillions in reparations for long-distant wrongs to exercise some caution, especially as today’s circumstances make the case for reparations vastly less strong than it was in 1920. Precisely what damage today is to be repaired? Who are the victims now? Who alive in the 2020s is responsible for events in the 1720s? How can the monetary cost of remote harms be reasonably calculated? Would resentment be caused by the imposition of reparations? How damaging might that be to present society and to the relationship between payers and receivers? Could resources be better used to relieve urgent 21st-century needs, rather than to pay the distant heirs of long-dead victims?

Those seeking to benefit from enormous sums in reparations may be understandably disinclined to such reflections. But could not a major public institution such as the Church Commission – chaired by the Archbishop of Canterbury and including the Prime Minister, the Lord Chancellor, and the Speakers of the two Houses of Parliament – be relied upon to exercise prudence and judgment? It seems not. After obtaining research of its archives by a firm of accountants which formed the substance of ‘Church Commissioners’ Research into Historic Links to Transatlantic Chattel Slavery’ (2023), the Commissioners have announced the intention of creating a £100 million ‘impact investment fund’ in reparation for the Church’s having profited from slave trading; and they have further welcomed a report by an oversight group which has proposed increasing this sum to ‘target assets of over £1 billion’.

Their language has oscillated between the unambiguous use of the word ‘reparation’ and the vaguer expression ‘healing, repair, and justice’ – a distinction without real difference, as can be seen in the sum being offered, its supposed derivation (‘a historic pool of capital tainted by its involvement in African chattel enslavement: Queen Anne’s Bounty’) and the extraordinarily unspecific and unmeasurable aims of the project (to ‘generate returns that would replenish and enable funding to be deployed to relevant causes in the African diaspora, ideally in perpetuity’). The disbursement seems to be practically unconditional, and principally aimed at the black middle class (‘Black-led businesses… Black fund managers… brilliant social entrepreneurs, educators, healthcare givers, asset managers and historians’, as the Oversight Group of the Church Commission lists them).

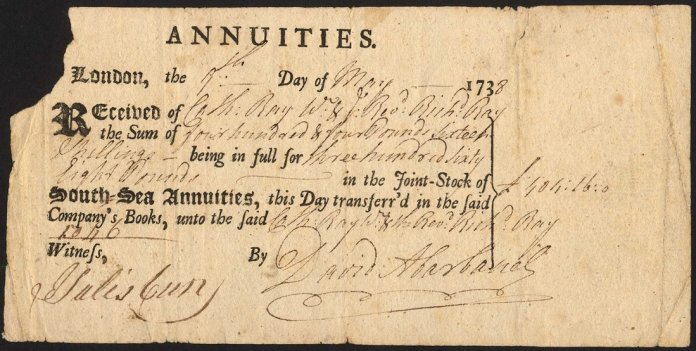

The basis of the reparations policy is this. The administrators of Queen Anne’s Bounty, a royal fund for the support of the clergy, accumulated investments of £200,000 in the South Sea Company between 1720-39. This company for a short period traded slaves to Spanish colonies. Therefore, it is concluded that the Church profited from the slave trade, and hence is in possession of ill-gotten gains it should not have – and which must be given away. The Commissioners have estimated that those ill-gotten investments now amount to £440 million.

It is easy to imagine how those pushing for reparations will attempt to apply the same formula to other great institutions. If the Church of England recognises a moral obligation to pay reparations, who can claim exemption amid the ensuing rush of demands? Indeed, this is part of the Oversight Group’s plan: ‘other institutions once complicit in African chattel enslavement’ will be expected to follow suit. The monarchy, the great museums, the universities, major industries, even ‘farming and fishing’ – all will surely face increased pressure to pay moral and financial tribute for the sins of ancestors.

Except that the Commission’s whole case is highly dubious. According to a recognised expert, Professor Richard Dale, the Commissioners and their accountants have misunderstood basic facts. The South Sea Company was only in part a trading company, which undeniably (though rather unwillingly) provided slaves for a short period to the Spanish empire as part of a deal allowing it to export manufactured goods.

The company’s investors and directors disliked the deal, as they knew that trading in slaves was not likely to be profitable. So it proved: the company made losses on its brief slaving activity. But it had a safer and bigger source of income, as it was also a holding company for government debt in a scheme for privatising the huge liabilities incurred during the decades of war that followed the Glorious Revolution. Over-optimistic investors triggered an unsustainable rise in the share price – the famous South Sea Bubble – but wiser investors remained sceptical.

Read it all in the Spectator