“Our Image of God Must Go.”

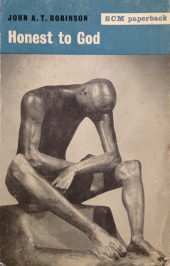

That was the title of an essay in The Observer in March 1963, an excerpt from Honest to God by New Testament scholar John A. T. Robinson, the bishop of Woolwich in the Church of England. The book took the religious publishing world by storm, selling over a million copies, stimulating all sorts of conversations about the future of the church, and stirring up controversy and calls for Robinson’s resignation.

For a long time, I’ve heard about Honest to God. People point to the publication as an inflection point in the history of Christianity in Great Britain and in mainline Protestant circles in the United States, claiming it as either a bold step toward progress in bringing Christianity into conversation with the modern world or as a radical departure from historic Christianity that has ended in theological disaster.

In light of this influential work turning 60 this year, I found an old, discolored paperback edition, the cover barely clinging to the book, and marked up my way through the text. It’s a short proposal that casts a long shadow.

It’s Time for Something Radical

The book begins and ends with Robinson casting himself as a reluctant revolutionary. He assumes the role of a wise and reasonable church leader pressed upon by the current moment to do whatever it takes to save Christianity and stave off church decline.

What’s necessary is something far more radical than “a restating of traditional orthodoxy in modern terms” (7), he says, something that diverges from the path taken by Dorothy Sayers, C. S. Lewis, and J. B. Phillips (15). The moment demands more than mere translation of traditional Christian teaching. If the church is to avoid shrinking into “a tiny religious remnant,” we need “a much more radical recasting” whereby “the most fundamental categories of our theology—of God, of the supernatural, and of religion itself—must go into the melting” (7).

Sights on the Supernatural

Throughout the book, Robinson appeals to the work of Paul Tillich, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Rudolf Bultmann. They’re his conversation partners, the German philosopher theologians at the vanguard of a new kind of Christianity, whose proposals look most promising. The survival of Christianity is at stake, he says. “There is no time to lose” in seeking to “recapture ‘secular’ man.” The way forward is to adopt a new conception of God that, in the end, is more faithful to Christianity than the traditional formulas so often misunderstood in modern times (43).

Robinson takes issue with the God of popular imagination—the old man upstairs who intervenes in human affairs much like a doting grandfather or absent caretaker. Rather than correct these misconceptions of God with a deeper exploration of Scripture or by interrogating the therapeutic and deistic assumptions that lead to such a vision, or by challenging dualistic readings of the biblical text, Robinson sets his sights on “supernaturalism” and “the miraculous.” The church should heed the naturalist critique of supernaturalism because it exposes many of Christianity’s cherished beliefs as “an idol” we must no longer cling to. At the same time, he insists, the Christian faith has a word for thoroughgoing naturalists, lest God become little more than “a redundant name for nature or for humanity” (54).

Robinson embraces Tillich’s description of God as “the ground of our being,” claiming it to be a “great contribution” to the project of reinterpreting transcendence in a way that “preserves its reality while detaching it from the projection of supernaturalism” (56). He celebrates this move toward the abstract—away, it seems, from the covenantal faithfulness of Yahweh, seen in the gritty life of Israel. (Much more could be said about the flattening of Old and New Testament particularity here, but I digress.)

Christianity for a New Day

Robinson’s new image of God leads to a consistent redefining of traditional Christian doctrine, with both God and his works morphing into something less personal and less concrete (and if I’m honest, much less interesting).

Robinson dismisses arguments for the divinity of Christ that appeal to Jesus’s self-conception or speech, such as Lewis’s famous trilemma of Jesus being either a liar, a lunatic, or the Lord. Jesus never claimed to be God personally, he tells us, only the One who brings God completely (72). Traditional theologies of the atonement are set to the side. The kenotic theory of Christ’s incarnation is preferred. Gone are the New Testament’s frightening images of hellfire; eternal judgment gets recast for a modern age as “union-in-estrangement with the Ground of our being,” following Paul Althaus’s description of “inescapable godlessness in inescapable relationship to God” (80).

Christian morality gets altered also, with Joseph Fletcher’s “situational ethics” put forth as the only option for “a man come of age” (116–17). “Life in the Spirit” means living with “no absolutes but his love” (114), which “will find . . . its own particular way in every individual situation” (112). Actions once considered wrong or sinful (such as sex before marriage) are not necessarily so, once love becomes the standard that renders moral laws irrelevant.

Love alone, because, as it were, it has a built-in moral compass, enabling it to ‘home’ intuitively upon the deepest need of the other, can allow itself to be directed completely by the situation. It alone can afford to be utterly open to the situation, or rather to the person in the situation, uniquely and for his own sake, without losing its direction or unconditionality. It is able to embrace an ethic of radical responsiveness, meeting every situation on its own merits, with no prescriptive laws. (115)

Here’s the way Robinson’s proposal works. He adopts, almost without question, the assumptions of his sophisticated contemporaries but then pushes back gently at some of the more far-reaching implications of modern views. Christianity comes across less like an authority heralding the truths of divine revelation and more like a quiet conversation partner meekly lifting a hand every now and then from over in the corner, hoping to be heard. Enlightenment naturalistic views are assumed; traditional Christianity gets interrogated.

In the end, as the reluctant revolutionary, Robinson calls the church to overcome her obstinate opposition to radical change and embrace a “metamorphosis of Christian belief and practice”—a recasting that will “leave the fundamental truth of the Gospel unaffected” yet still require “everything to go into the melting—even our most cherished religious categories and moral absolutes” (124).

Successful Disaster

Read it all at the Gospel Coalition