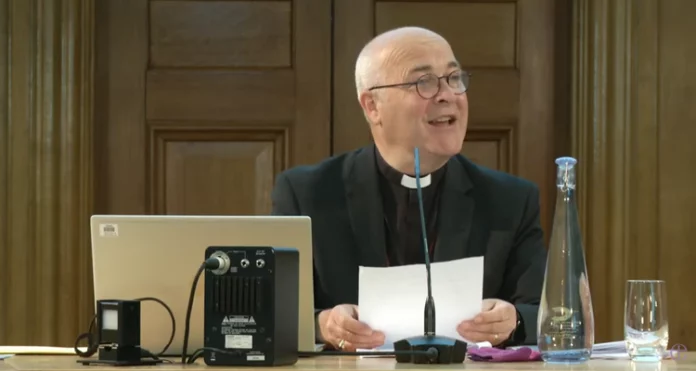

While England’s cricket team is battling it out against the Aussies in Yorkshire, the Archbishop of York has picked a fight with God. Stephen Cottrell yesterday addressed the General Synod of the Church of England, arguing that praying to God as ‘our Father’ is problematic.

Understand, unlike the Aussies who play cricket within the rules of the game, Cottrell thought it smart to break the rules of both the Bible and society. As Cottrell would surely know, refusing to use someone’s preferred gender pronouns is paramount to heresy in today’s Western culture. More than that, God gets to choose how he is addressed, and yet the Archbishop of a church has announced that he is stepping outside the crease and he is proud of it.

“For if this God to whom we pray is ‘Father’ – and, yes, I know the word ‘father’ is problematic for those whose experience of earthly fathers has been destructive and abusive, and for all of us have laboured rather too much from an oppressively, patriarchal grip on life – then those of us who say this prayer together, whether we like it or not, whether we acknowledge it or not, even if we determinedly face away from each other, only turning round in order to put a knife in the back of the person standing behind us, are sisters and brothers, family members, the household of God.”

Yes, Stephen Cottrell hasn’t downright rejected Jesus’ call for us to address God as Father; doing so is a step too far for a Church of England Archbishop…for now. Nonetheless, the Archbishop has denigrated the idea of praying ‘our father’ and maligned Jesus in the process.

The Archbishop of York offers 2 reasons why we may (or should) be reluctant to ascribe God as Father. First, he says that some people have terrible fathers. This is sadly true. It is also the experience of many that they have had cruel, abusive, or difficult mothers. As we minister to people we certainly don’t wish to ignore the fact that in our congregation and in the wider community, many people have been mistreated by their Dad. God as Father is unlike them. He is perfect in love and trustworthiness and care and goodness and strength. Praying to ‘our father’ isn’t problematic, it is the ultimate resolution to every need and hint of longing for a good father.

Cottrell’s second objection is more concerning. He asserts that father language smacks of patriarchy. Is the Archbishop implying that Jesus lacks pastoral awareness and that Jesus was complicit in advocating a system of injustice? Patriarchy has become shorthand for sexism, misogyny, inequality, and abuse. In drawing such a close connection between Jesus’ words and patriarchy, the Archbishop comes perilously close to calling Jesus a blasphemer. On this, he doesn’t quite step outside his crease, but he is tempting both keeper and umpire. How far can he go and what can he get away with?

Of course, it was not uncommon for the religious leaders of the day to call Jesus a blasphemer, especially as Jesus identified God as Father and he as God’s Son. On one occasion, Jesus called out his opponents,

“what about the one whom the Father set apart as his very own and sent into the world? Why then do you accuse me of blasphemy because I said, ‘I am God’s Son’? Do not believe me unless I do the works of my Father.” (John 10:36-37)

Jesus wouldn’t be defined by the theological position of Jerusalem’s religious mafia, including their progressive teaching on sexuality. Let’s remember, the Pharisees justified their own sexual inclinations by trying to rewrite the Scriptures whereas Jesus reaffirmed the goodness of God’s design and pattern that is laid out in Genesis chapters 1 and 2.

That’s the thing, when you play with the Bible’s teaching on sexuality and gender, you end up fiddling with the doctrine of God. Stephen Cottrell is among the majority of English bishops who supports the introduction of prayers of blessing for same-sex couples.

A distortion in our anthropology naturally leads to ripping apart the doctrine of God. In recent times Australian politicians have employed a vague and boundary-less concept of a loving God to justify all manner of gender and sexual proclivities. It is one thing for political representatives to fudge God, but it is quite another for a church leader to mislead the people of God.

The pressures to give in to current waves of sexual and gender attitudes is tremendous and standing on Scripture can cost you friends, family and work. The Church should be the one sanctuary where believing God and trusting Jesus isn’t debated and where you’re not called names for sticking with the Bible. Sadly, not so in many cathedral walls and brick parishes.

It shouldn’t surprise us to see ministers who reject Jesus’ teaching on marriage, also cast doubt on what Jesus teaches us about God.

If we think that our understanding of humanity doesn’t interfere with our understanding of God then either, we haven’t been paying attention to ecclesial debates or we’ve convinced ourselves that these matters are not so important.

In order to sustain the view that God is pleased with same-sex marriage and that any gender distinction is arbitrary and even immoral, pastors, and theologians, eventually know that they have to deal with the question of God’s self-revelation. Of course, there is nothing new in Cottrell’s comments. These have been circulating around liberal theological circles for decades, like the boos from a drunken crowd at the Ashes. There is nothing original in his remarks, but they reinforce the perilous state of the Church of England.

The Triune God is revealed to us in the words of Scripture as Father and Son and Holy Spirit. While there are a few examples in the Bible where a feminine simile is used to describe God and by God, there are no feminine metaphors or names used, whereas masculine ones are found frequently.

The Holy Spirit is spoken as he, ““When the Advocate comes, whom I will send to you from the Father—the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father—he will testify about me.” (John 15:26)

The Son of God is the son and not the daughter, and the Son incarnate became a man, not a woman.

God the Father is the Father.

On the question of similes and metaphors, it’s important to observe a linguistic distinction.

Read it all at Murraycampbell.net

[…] the true nature of fatherhood through Christ.” One blogger who had his op-ed reposted on Anglican Ink even went so far as to say Cottrell had “picked a fight with […]

[…] the true nature of fatherhood through Christ.” One blogger who had his op-ed reposted on Anglican Ink even went so far as to say Cottrell had “picked a fight with […]