The Archbishop of Canterbury practised crowning the King and Queen in a bedroom before the coronation last month.

Justin Welby said that he rehearsed the sacred part of the ceremony with a replica crown, but got to handle the St Edward’s Crown just days before officiating over the ceremony at Westminster Abbey on May 6.

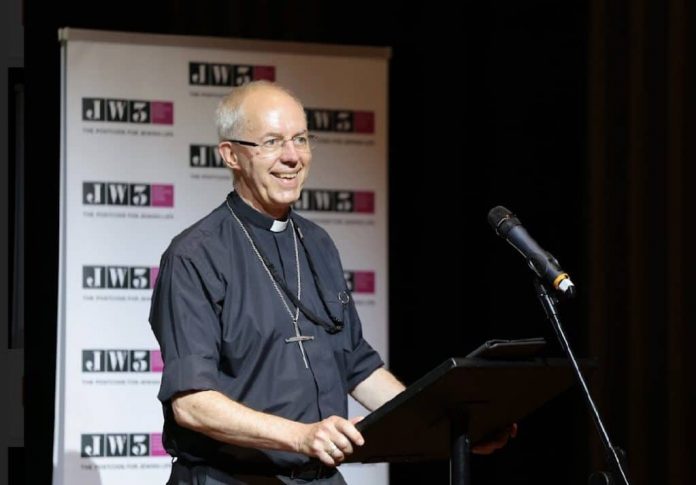

In conversation with ITV news anchor Julie Etchingham at the fifth Religion Media Festival at the JW3 Centre in north London yesterday, the archbishop said: “They sat in their bedrooms and I crowned them again and again and again.”

When a surprised Ms Etchingham questioned him about being in the royal couple’s sleeping quarters, he said there was “definitely a bed”.

“It was a bedroom in Clarence House,” he added. “I didn’t think it was polite to ask.”

The dry runs paid off and playing a leading role was a “huge privilege” he said. “We had rehearsed it so often that I was able to be in the moment and just be with the King on this enormously sacred moment for him, but also for the country, and enjoy it.”

The coronation will be remembered for generations to come and Archbishop Welby’s involvement will be regarded as part of his “legacy”, Ms Etchingham said. But she did not shy away from stressing that the legacy was about a lot more than joyous occasions.

The decade since he took over has seen him steer the Church of England through challenging times including the pandemic, the death of Queen Elizabeth and the cost-of-living crisis.

He has presided over a deeply divided Anglican community, both in Britain and overseas, while attendance numbers have also been in decline.

The 2021 Census revealed that fewer than half of the people in England and Wales consider themselves to be Christian. A total of 46.2 per cent of the population of described themselves as Christian, down from 59.3 per cent a decade earlier.

Ms Etchingham said attendance at CofE services had dropped by a third and asked to what the archbishop attributed the “alarming drop”.

Though he said that it was too early to judge his legacy, he added: “The further decline in the church is something that in the end, even if I’m not — and I’m not saying I’m not — responsible for, I’m certainly accountable for. So that I personally count as failure.

“Lots of people will tell me I shouldn’t have said that, but that’s what I feel personally. Yes. I’m not sure I know what else could have been done because in the end, the church is not in the hands of individual archbishops. The future of the church, survival or otherwise, does not depend on archbishops. It depends on God and the providence of God.”

Ms Etchingham grilled the archbishop on what she called the “endless and deep divisions over sexuality”, with wider society seeing the church as being “on a completely different planet”.

Her comments came just days after Archbishop Welby called on the Anglican Church of Uganda to reject the country’s new anti-LGBTQ+ law. Nevertheless, he explained that the issue of same-sex relationships was a complex one, given the reach of the Anglican Communion

Earlier, the festival began with his address, in which he outlined the enormous reach of the Anglican church, which encompasses more than two billion people worldwide.

And while the number of Christians might be in decline in Britain, he said religion played a role in the lives of 80 per cent of the global population. “Even the Anglican Communion spans about 80 or 85 million people, across 165 diverse countries. The typical Anglican is a woman in her thirties, in sub-Saharan Africa, likely an area of conflict, who lives on less than $4 a day,” he said.

His address focused on the church’s relationship with the media, where he admitted that he “actually quite enjoys” being interviewed. However, he went on to add: “One of the relatively few things I’m looking forward to in retirement is being able to read the paper without worrying about whether I’ll see my own name.”

Unsurprisingly, that comment led Ms Etchingham to question him about his plans for retirement. He said that he was “obliged” to step down by his 70th birthday on 6 January 2026, but would not be drawn further on the matter.

He also remained fairly tight-lipped on Ms Etchingham’s questioning about his views on former prime minister Boris Johnson, asking: “Was this a man morally fit to lead Britain?”

“That’s for the parliamentary process to conclude, not me,” he replied.

He admitted that there was “very certainly a moral take on leadership” and said “leaving the constitution and the country in a better place that you found it” was the “key objective of politics”.

The Commons Privileges Committee is due to publish its findings on Wednesday, on whether Boris Johnson misled parliament, but Justin Welby pointed out: “They’re not explicitly examining his moral character.”

The archbishop was then asked for his views on Kate Forbes, who in March had been considered a frontrunner to replace Nicola Sturgeon as Scotland’s first minister but who found herself in a storm of media controversy over her Christian faith.

The archbishop said that Ms Forbes was treated unfairly, adding: “It was an entire failure of many newspapers and reporters and radio and TV.”

He said her faith was presented as an “eccentric view” and that her rival, Humza Yousaf, who went on to take the role, was not subject to the same scrutiny. “People didn’t challenge him in the same way and I think there was a noticeable difference,” he said.

Questions about his own experience of the “media pile on”, led to Ms Etchingham asking the archbishop his views on cancel culture.

“I think there’s an absence of forgiveness,” he said. “There is an absence of the possibility of redemption, so people are treated as though they were the worst villain on earth and where do you then go when terrible things happen?

“If you’ve treated someone in sport or something like that as the absolute final say in evil, how do you deal with [the Russian army’s massacre of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians at] Bucha? How do you deal with South Sudan or Sudan?”

When asked how it felt to be at the centre of such a media frenzy, he replied: “It feels very uncontrolled. There’s nothing you can do about it except stick your head down and wait and see what happens.”

Ms Etchingham asked the archbishop how the church’s moral voice has been affected by the outcome of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse and ongoing questions over those issues, as well as the former Archbishop of York rejecting the report saying he failed to act on such disclosures.

“Anyone who thinks that the Church of England can lecture from some high moral plain is in cloud cuckoo land,” said the archbishop.

“That is why it is such a catastrophic and total failure and the fact that there will always be safeguarding challenges. There always have been, but the difference is now that we’re open about it and transparent about it.”

He said that the stricter measures have been introduced but, in his opinion “until we have a fully independent safeguarding system … we cannot hold our heads up.”

Finally, she raised the issue of the personal grief that the archbishop has been through after losing a child.

He replied: “I think there is something about the personal experience of the faithfulness of God that enables you to know that in the end this isn’t actually about me at all. It’s about God’s people around the world in far worse situations than I’ve ever known or will ever know, and far better ones, and it’s about the providence and faithfulness of God who rescues us.

“The job of the church is to keep on saying that and not to be fearful, not to be frightened, not to be overwhelmed, not ever as archbishop to think it’s about me. It’s not about me.”

Read it all at the Religion Media Centre