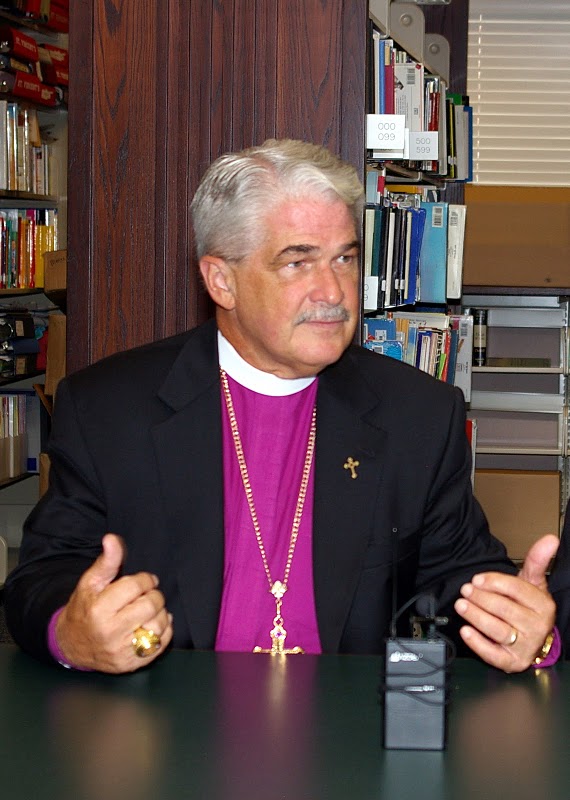

The Rev. Rt. Jack Iker, also known as the “lion of Fort Worth,” died Oct. 5 at the age of 75.

Iker is survived by his wife, Donna Iker, their three daughters and four grandchildren.

Born Aug. 31, 1949, Iker was a native of Cincinnati, Ohio. He served as a Rector of the church of the Redeemer in Florida before being consecrated as bishop coadjutor, someone who assists a diocesan bishop, for the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth on April 24, 1993.

Iker became the third bishop to serve the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth on Jan. 1, 1995.

The lion of Fort Worth nickname derives from Iker’s middle name, Leo, said Fr. Randall Foster from St. Johns Church, an Anglican parish in Fort Worth.

“He was quite instrumental in leading the traditionalist elements in the Episcopal Church during our separation from that body 15 years ago,” Foster said.

On Nov. 13, 2008, after 13 years in the role, Iker left the Episcopal Church. He became the face of the split within the local diocese that made Fort Worth a focal point in the widening national schism among Episcopalians with opposing viewpoints on ordaining women and gay priests and blessing same-sex unions.

“We are taking a stand for the historic faith and practice of the Bible, as we have received them, and against the continuing erosion of that faith by [the Episcopal Church],” Iker wrote in a 2008 newsletter.

Some parishioners decided to stay with the national church. About 15,000 congregants from 48 churches followed Iker’s lead and later aligned with the Anglican Church of North America.

The split sparked a 12-year legal battle over which group was the true Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth and who owned the five churches caught in the middle of the conflict: All Saints’, St. Christopher, St. Elisabeth,Christ the King and St. Luke’s in the Meadow. One, St. Stephen’s, is in Wichita Falls.

The lawsuit made it all the way up to the Texas Supreme Court, which decided in 2020 that the buildings belonged to Iker’s group, allowing them to retain the rights to $100 million in property assets. The group with the national Episocpal Church appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

“In many ways, this has been like a civil war for the country. Families were divided, friends were divided, all those kinds of things,” the Rev. Canon Jay Atwood told KERA News in 2021. “It’s been difficult for people to come back together at the end.”

The Rev. Ryan Reed, the current bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth, called the decision a “turning point” for the diocese in a 2021 press release.

“His stance for the biblical Christian faith made him either a hero, both within our church or even within ecumenical circles, where he had good relationships, or it made him despised, depending on the perspective of the audience,” Reed said of Iker in an August interview. “He didn’t back down from what we’ve received in terms of Biblical faith.”

Toward the end of the legal disputes and a year before his retirement, Iker announcedin 2018 he was being treated for cancer.

Rev. Joel Hampton, canon to the ordinary, remembers that as a “difficult time,” as Iker was trying to lead a group of thousands of parishoners, battling cancer and going through the process of electing a new bishop.

Hampton met Iker in 2006 and served alongside Iker as a chaplain. Iker was the one who ordained him as a deacon and then a priest. He remembers seeing Iker sitting in his office chair, wearing a ball cap that covered the loss of hair from chemotherapy and helped him stay warm.

“Throughout that whole period of what looked at the time, in 2018 and 2019, to be a terminal battle of cancer, he never stopped being a leader and a guide,” Hampton said. “For a lot of us, he was the embodiment of what it means to be courageous and steadfast.”

Iker retired as bishop on Dec. 31, 2019. Reed became Iker’s successor in 2020.

But the two’s history goes further than that. Reed remembers meeting Iker as a youth minister at St. Andrew’s Anglican Church in downtown Fort Worth in the early 1990s.

One of the things that Reed said he always noticed about Iker was that “through all the years of persecution, he never lost his sense of humor.”

Iker was known for a very serious, focused and mission-oriented public persona, Reed said.

“But one-on-one or in a small group, his sense of humor would come out. It was a good sense of humor,” Reed said, recalling the jokes Iker would share at monthly dinners together.

Iker’s cancer resurfaced in the summer of 2024, and his family announced in an August Facebook post that he had entered hospice care. Reed remembers taking him to dinner right before his 75th birthday.

“He was a pastor’s pastor,” Reed said. “His first loyalty was to the clergy and their families. If you did something wrong, he would discipline you, but the purpose was to correct you out of love or hold you accountable.”

This obituary will be updated with arrangements for Iker’s funeral.