I seem to be developing a bit of a reputation for defending the indefensible.

Not the best trait to become known for, perhaps, but after some reflection, I’m starting to come to terms with it.

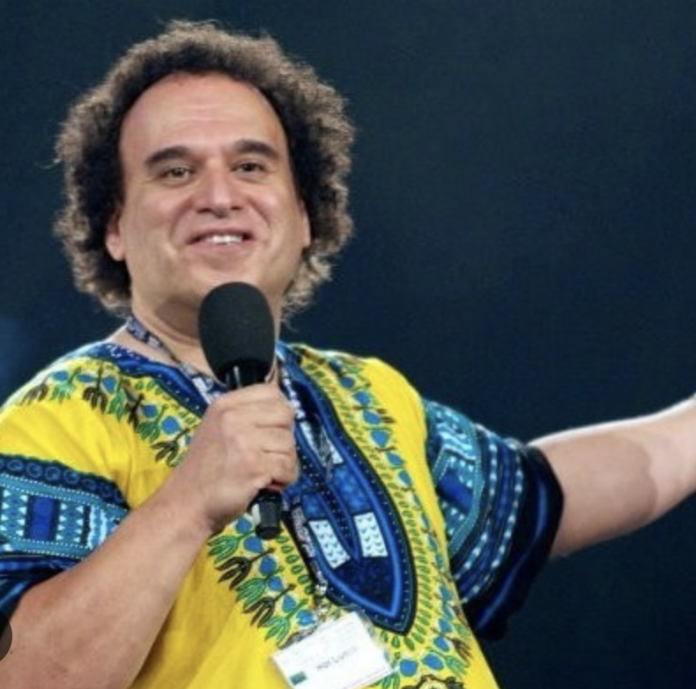

The indefensible act – or individual, in this case – on my mind today is the fallen vicar and one-time hero of mine Mike Pilavachi: he of flowing curly locks fame, recently de-famed for “using his spiritual authority to control people”.

I was recently back at the site of the Soul Survivor festival where he rose to fame – a field in Shepton Mallet – for another Christian festival, and it was hard not to think back to those days long past, when I and thousands of other young people used to look up to “Mike”, as he was simply and fondly known, for guidance.

I can still vividly remember the big Greek’s humour and gentle tone of voice as he sought to reassure us that however odd something might seem – perhaps an individual was crying out or even shaking – it was “OK”. And I believed him. And, honestly, at least regarding the spiritual experiences of those days, I still do.

But following the recent revelations, and “Mike’s” very public humiliation, he too has now understandably moved into the category of individuals for whom finding forgiveness is not the most natural response.

Yet, once again, I find myself in the almost counter-intuitive position of wishing to spring to his defence. Not because I wish to condone what by the sound of things was some very inappropriate behaviour, but because I recognise my own fallibility and would hope that were I to err, even to such a severe degree, someone else might seek to save me from the scrapheap.

I wrote recently in The Critic about my hope for reform for even the worst offenders, not because the individuals deserved to be defended – in most of the cases I outlined, their deeds were dark indeed – but because I could identify with the human weakness that makes it possible for humans to sink even to such depths.

In the months since the revelations about “Mike” first came to light, I have been reminded frequently of the song by Marcus Mumford, ‘Stonecatcher’, which seems to take inspiration from the biblical story of the woman caught in adultery, about whom Jesus famously stated, in John 8:7: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.”

Those present, so the story goes, eventually all leave, leaving only Jesus, who equally famously goes on to say to the woman: “Has no-one condemned you? Then, neither do I.”

Jesus ends by calling on her to “leave your life of sin”, which seems to me to be another way of saying: “Reform yourself.”

Mumford goes even further than Jesus – if such a thing were possible – by singing that he desires not only to lay down his stones but even to stand in the way of those thrown by others.

“Let me be a stone-catcher, please,” he sings.

Because he too recognises, as he puts it in the song, that it “could have just as well been me, brought before them, head down in that midday heat, only defined by my most heinous deed. Would you trace a finger through the dust?” – an allusion, presumably, to Jesus’ first act – upon finding the woman about to be stoned – having been to write something on the ground.

It is only after the accusers continue to hurl their verbal stones at the woman that Jesus utters his provocative line about those without sin casting the first stone.

And it is this aspect of the accusers – dropping their stones – that I can identify with, being only too aware of my own shortcomings and failures, even if they may not yet have brought me to public disgrace.

Of course I hope that I never shall be disgraced, but along with the apostle Paul in Romans 7 – and in fact many other biblical characters and passages – I fully recognise in myself the propensity for wretchedness.

And with that very much in mind, I choose to hope that even were I one day to meet public disgrace – for whatever heinous deed – someone might seek to step in front of those wishing to throw stones at me, whether metaphorically or literally.

Which brings me back to “Mike”, towards whom countless verbal stones have been thrown in recent months – not without justification, of course – and I find myself wondering again: what if it had been me?

What if my darkest secrets had been uncovered? What response would I hope for?

And here I come back once more to Mumford for inspiration, and particularly to the fact that the whole album upon which ‘Stonecatcher’ features is about him desperately trying to come to terms with the abuse he suffered as a child and even, staggeringly, striving to forgive his abuser.

“I’ll forgive you now,” he sings in the last song on the album, aptly titled ‘How’.

“As if saying the words will help me know how,” he goes on. “Please help me know how.”

All of which, to me, is both an incredibly admirable thing to attempt to do for one’s abuser and also something I wish to aspire to, were I ever to be the victim of abuse.

Like me, Marcus Mumford grew up in a Christian home – the son of church leaders of the same Vineyard movement I attended right around the time I used to attend Soul Survivor – and it is perhaps this fact that has ingrained in us both the almost irrational drive to seek to forgive even those who have committed the gravest offences.

For while a lot of people think that the Christian message is about being good, in my opinion it’s actually far more about how we can all find forgiveness, regardless of what we may have done.

And that’s a message, I believe, that has the potential to bring hope – and even reform – to anyone, however far they may have fallen.