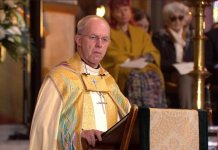

Orthodox Anglicans have something to cheer in this otherwise dismal year. On Ash Wednesday 2023, Anglican leaders in the Global South rejected Canterbury’s decision to bless same-sex unions. They declared they are “no longer able to recognize the present Archbishop of Canterbury, the Rt Hon and Revd Justin Welby, as the ‘first among equals’ Leader of the global Communion.” And in April of this past year, another gathering of Anglican leaders joined this departure from Canterbury. In total, 85 percent of the Anglican Communion is determined to “reset the Communion on its biblical foundations.” As progressive Anglicanism in the Global North continues to decline, orthodox Anglicanism in the Global South is booming. There are more Anglicans in church on Sunday morning in Nigeria alone, for instance, than in all of North America and Great Britain combined. Yet amidst this energy, there are worrying signs.

Global South Anglican leaders opposed to same-sex marriage are preparing to bind themselves with a document that rests on ambiguous theological foundations. Their bishops will gather in June 2024 to review and reaffirm the “Cairo Covenant,” first written in 2019 to “strengthen Global South identity, [establish doctrine] in keeping with orthodox faith . . . and establish conciliar structures [that hold] each other accountable to a common dogmatic and liturgical tradition.” The new covenantal structure is a vast improvement over Canterbury’s regime because it provides for genuine doctrinal accountability. But there are parts of the document that may contradict traditional Anglicanism, and need further review.

The problem is that the Cairo Covenant uses the language of sola scriptura without sufficient qualification. The term sola scriptura suggests that the Bible by itself can ensure orthodoxy without the guidance of the historic Church. The Covenant defines sola scriptura as “the Scriptures’ authority over the Church,” which itself is “a creature of the divine Word.” Yet as students of church history know, the Church produced the Bible and protected it against heretical interpretations at ecumenical councils like Nicaea. So while the divine Word guided the Church as it protected the Bible, the Bible was a “creature” of the Church—not the other way around.

Athanasius, for example, recognized the critical role of church tradition in his battle against Arianism. Arius argued from the Bible alone (using such verses as Jesus’s statement “The Father is greater than I”) that Christ is more than a man but less than fully God. In his epistle to the African bishops, Athanasius insisted that proper biblical interpretation requires “the sound Faith which Christ gave us, the Apostles preached, and the Fathers, who met at Nicaea from all this world of ours, have handed down” (emphasis added). The Fathers at Nicaea taught that Christ is homoousios—of the same nature (as the Father). Athanasius pointed out that while this Greek word is not in the Bible, its concept is, and we need the Church’s tradition to teach us this.

The Anglican reformers of the sixteenth century also saw the need for the ecumenical councils and creeds to interpret the Bible properly. Bishop John Jewel wrote in his Apology of the Church of England that the English reformation was “confirmed by the words of Christ, by the writings of the apostles, by the testimonies of the Catholic fathers, and by the examples of many ages.” When Anglican bishops approved the Thirty-Nine Articles in 1571, they declared in canon law that preachers were not to assert anything different from Scripture or “what the Catholic fathers and ancient bishops have collected from this selfsame doctrine.” They added that the Articles “in all respects agree with” the Fathers and ancient bishops.

The greatest theologian of the English Reformation was Richard Hooker (1554–1600), whose massive Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity appealed to the Fathers 774 times, as often to those in the West as to those in the East. Bishop Francis White (1564‒1638), bishop of Ely, wrote, “The Church of England in her public and authorized Doctrine and Religion” looks to Scripture as “her main and prime foundation” but after that “relieth upon the consentieth testimony and authority of the Bishops and Patrons of the true ancient Catholic Church; and it prefereth the sentence thereof before all other curious and profane novelties.”

The Cairo Covenant makes other statements that separate Scripture from the Church’s interpretation. For example, it uses a polemical Latin axiom from the Reformation: “Scriptura sacra locuta, res decisa est” (Sacred Scripture has spoken, the matter is decided). The Covenant fails to indicate that the magisterial reformers Luther and Calvin regularly appealed to the Fathers and the ecumenical councils in their arguments for the meaning of the Bible.

Foundational Anglican documents support the principle that Scripture should be interpreted with deference to ancient church authorities. The Chicago Quadrilateral (1888) asserts that the Nicene Creed is “the sufficient statement of the Christian Faith.” The Jerusalem Declaration (2008) maintains that the Bible is to be taught in its “plain and canonical sense, respectful of the church’s historic and consensual reading.” The Declaration upholds “the four Ecumenical Councils and the three historic Creeds as expressing the rule of faith of the one holy catholic and apostolic Church.”

The Cairo Covenant asserts the final authority of Scripture, which is commendable. But it does not acknowledge that the guardian of Scripture has always been the Church’s councils, creeds, and teachings.

It was this omission of tradition that caused progressive Anglicans to go astray decades ago when they started ordaining women to Holy Orders, an innovation rejected by tradition for nearly two millennia. Anglicans who would sign the Cairo Covenant in its present form should recognize that the way to same-sex blessings was partly paved by this Anglican approval of women’s ordination in the 1970s. A new hermeneutic was established whereby Anglicans dismissed both tradition and the plain sense of Scripture in order to make spurious biblical arguments about justice and equality. In both debates—over Holy Orders and marriage—tradition was jettisoned in order to sidestep the Bible’s teachings. The appeal to Scripture alone was convenient in the process. Only prima scriptura could have prevented this devolution to heresy.

This is not a disagreement over the final authority of Scripture. We suggest replacement of sola scriptura with prima scriptura, Scripture’s primary authority protected by the wisdom of the Great Tradition—or, as Aidan Nichols has put it, reading Scripture with the Church’s eyes of faith. Prima scriptura protects orthodoxy and the final authority of Scripture.

Connected to this issue is another potentially fatal error in the Cairo Covenant: The document calls for the creation of a new body of clergy and laity that will be given final authority to authorize “innovations” that would change its doctrine. But this move, while ostensibly protecting orthodox doctrine, opens the door to doctrinal innovation. In one place, the Cairo Covenant states that bishops have final authority; but later, the document contradicts that eccelesiology by calling for this new body of higher authority that includes laity. This error threatens to undermine the orthodoxy that was protected by prima scriptura and episcopacy before the twentieth century.

We recognize that many of those poised to sign the Cairo Covenant do not believe that sola scriptura is nuda scriptura—Scripture outside the protection of the Church’s traditional teaching. Many of these bishops are in fact opposed to women’s ordination as a violation of the tradition’s Holy Orders.

But the problem lies in the plain sense of the text. While most of today’s bishops might agree with prima scriptura, their sons and daughters will learn from the Covenant’s plain sense that we can ignore tradition when interpreting the Bible. This will be easier to do when—as is likely—the world’s condemnations grow louder and its financial coercions multiply against Christians who fail to approve what the world considers just and moral. If and when these sons and daughters yield to these greater temptations—occasioned by the problematic language of the Cairo Covenant—the Anglican Communion risks becoming one more liberal Protestant denomination.

While the Anglican Communion is being reset, as it ought to be, let us also suggest revising the language of the Cairo Covenant so that it better reflects the thinking of historic Anglicanism.