I HAVE COMPLEX AND PROFOUND FEELINGS of affection and protection for Canterbury Cathedral. I grew up in her shadow during my teenage years, having been sent to the Cathedral school that surrounds her.

For five years I lived beside and around her. As I explored her almost daily, a relationship between us developed. Like a person she had different aspects to her character. Parts of her were “easy-access”, and other parts were intense and complex. The intense and complex places were where the scent of holiness had grown and the atmospheric pressure was somehow more intense.

I was seduced first by music.

As a choral scholar I had to sing in liturgies I wouldn’t otherwise have bothered with. But in the depths of the Crypt, after battling through the darkness of early morning fog before dawn, I found myself singing mysterious haunting plainsong as part of the most exquisite liturgy –while the Eucharist was celebrated (by Anglican ministers) at an ancient Catholic altar. The candlelit darkness was full of “presence”, and somehow the music acted as a key that opened the pores of my adolescent soul.

It didn’t occur to me to ask myself if I believed or not. God was present. The place was infused in Him and by Him. Stone, soaked in prayer, become soft like a sponge and irradiated the present with the prayers and adoration of the past. It was TS Eliot who mused on the perichoresis of time, and the past in some mysterious way seeping deeply into the present there.

In the Crypt, one Sunday evening, I first met the Mother of God as a clergyman talked effectively about Mary. He described the quality of sacrificial love which keeps faith in the face of pain and dereliction, expressed as she kept watch at the Crucifixion. I understood and I found myself scribbling in response a small near-haiku poem which I have never forgotten. It emerged from my heart even if my head was a long way behind:

If ever I am to love, or be loved,

then let there be a cross,

with a foot to be filled…

And so began the seeds of a longing for Our Lady that only broke surface when decades later I became a Catholic. My life was like the Cathedral’s in reverse: I had begun as an Anglican and had to journey back to the foundations of the Faith, reversing the flow of national time, to put things back in order where faith had gone wrong.

The Nave was more diffuse atmospherically than the mysterious womb of the Crypt. But one night, in near total darkness lit only by a solitary line of candles, we sang the ever-glorious Advent responsory by Palestrina. Something in the ecstatic longing of this piece, carried upwards by an exquisite polyphony melting the heart, gave wings to the soul. I never knew how much my soul longed for God before this Advent Responsory carried it heavenwards in the luminous dark.

Just beyond the Nave, St Thomas Becket was martyred in the north western transept: a small corner by the little door into the cloisters they thought to bar to keep the assassins out, struck down by thuggish jobsworths on the make.

Who knew the archbishop clothed himself in a hair shirt until his body lay prone on those same flagstones soaked in blood?

Recognising him for a man brave enough to put conscience before abusive authority, I would sit on a stone ledge beside where he had been struck down, contemplating a would-be friendship with him. He became an odd but real friend in my adolescence. I was often to encounter what I took to be abusive authority, then and beyond.

In the windows above where fell are to be found remembrances of some of the 703 attested miracles that took place at his shrine.

Over the centuries before the Protestant vandals (not for the last time mistaking the meaning of the place) ravaged his shrine, the Cathedral saw an endless line of suffering pilgrims walk, stumble and crawl over these stones begging for healing. The healings came.

Petronella the desperate nun crippled by epilepsy – until healed at the shrine. Henry of Fordwich, off his head with violent madness, forced to live with his hands tied behind his back – until cured at the shrine. He left behind the sticks and ropes that had been used to restrain him in the past.

Every stone on that floor carried floor carried the weight of streams of desperate people. Both the questing suffering, but equally those who walked away healed, infused with joy at the miraculous answers to their prayers.

But today the Cathedral needs money. The new Dean, the Very Revd Dr David Monteith, says he wants to reach out to younger people as well as finding ways of raising the “large sums” the Cathedral requires to survive. He has scratched his head and has decided that the stones under his feet might be put to a different use than worship and pilgrimage.

He is opting instead for dancing, accompanied by booze and rave music. He wants to draw “the young” in to the Cathedral; them and their money. The Dean knows what he wants to do with their money, but he’s not so clear about what he wants them to get out of their entrance into the sacred space.

The “Rave in the Nave”, as it shall probably be known, will take place over two nights in February. It will be a strictly 18+ event, featuring plenty of alcohol and the music of the 1990s: Britney Spears, the Spice Girls, Eminem and the Vengaboys.

Dr Montieth has not been clear about how he intends to preserve the sacrality of the place while flogging the ravers booze and entertainment in the form of throbbing noise, raw sexual lyrics and self-expressive jiggling. Indeed he doesn’t seem overly bothered by the gap between the holiness of the sacred space he was appointed to care for, and the drunken epicurean pursuit of mind-numbing hyper-sexualised pleasure.

Unsurprisingly, this has drawn some criticism.

Cajetan Skowronski, a doctor in Sussex, has written an excoriating article in The European Conservative reminding his readers of the some of the lyrics that entertain silent disco dancers through their hi-tech headphones. They will hear, he writes,

“Profound exhortations such as the Real Slim Shady’s ‘My bum is on your lips, if I’m lucky you might give it a little kiss’, as well as his theological musings that ‘if we can hump dead animals and antelopes, then there’s no reason that a man and another man can’t elope,’ will be beamed into the headphones of intoxicated ravers while they contemplate the ancient architecture and 14 centuries of Christian history that they have stumbled into. A life-changing experience, which the Dean must be sure will yield many Damascene conversions.”

Some might well accuse Dr Montieth of severe paucity of judgement, and wonder how he came to occupy such an important position. But perhaps the situation says more about English Anglicanism than anything personally about the current Dean of Canterbury.

Entertainment seems to have become, if not a religion for Anglican cathedral deans, then at least an alternative to practising a religion.

They have taken their medieval Catholic shrines and, not content or aware of the presence of God, they have abandoned a pursuit of the sacred for a push for populist secular entertainment.

This has taken the form of indoor golf courses, helter-skelters and the installation of gin distilleries in buildings confiscated in a state coup from the Catholic communities that conceived them and built them – for very different purposes.

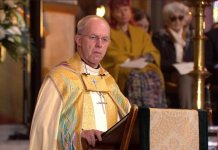

Well-meaning people hoping to save the Cathedral from impending desecration have started a petition begging the Archbishop of Canterbury to intervene. Sadly, because of how the Church of England does episcopacy, Justin Welby has neither power nor influence within the church in which he sits on the Throne of St Augustine.

It’s not a new trope, but on the other hand it’s not been much bettered. Those of us who have been pilgrims there and for whom love, longing and prayer were birthed and nurtured there are tempted to offer a different solution. Perhaps, if the CofE doesn’t know what cathedrals are for any more, they might consider returning them to their original owners, who still do.