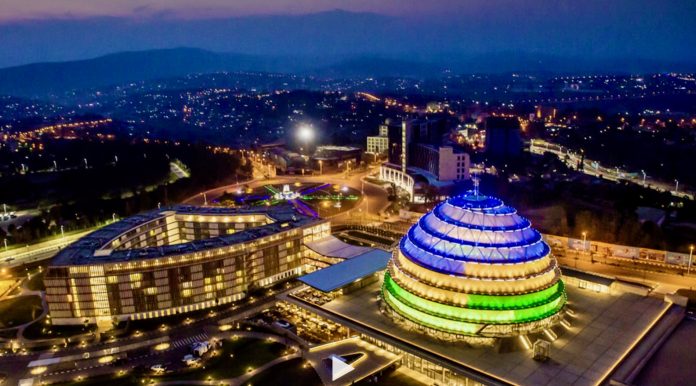

The recent Gafcon IV gathering in Kigali, Rwanda, will probably prove to be a watershed moment in global Anglicanism, but it carries within it the strong possibility of fragmentation. The ‘Kigali Commitment’, the Conference’s Statement, called for the ‘resetting’ of the Anglican Communion due to the departure from Biblical standards in human sexuality by the Church of England and others, and believes that the instruments of unity such as the office of the Archbishop of Canterbury cannot now be trusted to lead Anglicanism into a biblically faithful future.

There was much to rejoice in as representatives of around 85% of global Anglicanism affirmed their commitment to God’s Word and the supremacy of Christ to rule his church. Yet, it is exactly at this point, insisting on Christ’s rule over his church through his Word, that much of the danger of fragmentation emerges. Will Gafcon provinces apply the rule of Scripture and the norms of orthodox Anglicanism, the 39 Articles to their current practices, liturgies, and proclamation to enable them to carry out an effective decade of discipleship, evangelism and mission?

There are a number of significant tensions and unresolved issues within Gafcon. On the one hand, the general ‘feel’ of Gafcon is a strong commitment to the Reformed Evangelical doctrine of Scripture, the teaching of the 39 Articles, and the standards of the 1662 BCP. This is to be greatly welcomed as it is the very essence of Anglicanism. On the other hand, there are a couple of areas where this Reformed Evangelical commitment is in danger of being undermined.

Firstly, there is a strong Anglo-Catholic ‘Romanising’ influence at play. For example, when Bishop John Fenwick of the Free Church of England wrote his 2016 book, ‘Anglican Ecclesiology and the Gospel’, a deeply anti-Reformed Evangelical book, promoting the virtues of a more Catholic (as opposed to Protestant) Anglican church, praise and endorsement for it came from various Gafcon bishops. One was Bishop Nazir-Ali, who later converted to Romanism, and another was from Foley Beach, the current Chairman of Gafcon and leader of the Anglican Church of North America (ACNA).

When we look to the doctrine of ACNA, serious questions arise as to its commitment to the historic Reformed Evangelical faith of Anglicanism. In its 2019 Prayer Book for example, it upholds practices and liturgies that are more Roman than biblical. In its Catechism, whilst it recognises two Dominical Sacraments, baptism and the Lord’s Supper, it nevertheless affirms the other five Roman sacraments. In doing so, it says, ‘they were not ordained by Christ, as necessary to salvation, but arose from the practices of the Apostles and the early church or were blessed by God in Scripture. God clearly uses them as means of grace.’ It appeals for support to Article 25 of the 39 Articles, but astonishingly, it takes no notice of what that Article actually says concerning these extra five ‘sacraments’ that ‘…they are not to be accounted for Sacraments of the Gospel being such as have grown partly of the corrupt following of the Apostles…!

Not only does the ACNA 2019 Prayer Book undermine the Articles in this way, but also its liturgy undermines the Gospel of Grace and in particular the doctrine of Justification. We can see this clearly in its burial service where there are repeated prayers for the deceased. This makes null and void the certainty and assurance that we can have in this life through the Gospel, that to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord. It runs contrary to the 1662 BCP, which article 6 of the Jerusalem Declaration declared to be our ‘true and authoritative standard of worship and prayer..’ Again, it undermines classical Anglican Reformed Evangelical teaching, such as that taught in that most biblical and heart-warming Homily, ‘An Exhortation against the Fear of Death’, which sets so clearly, pastorally, and powerfully, the biblical, Anglican position on the impact of justification in relation to death.

The problem with these Romanising liturgies and interpretations of the Articles in whatever Gafcon Province they may be found in, is that they will seriously undermine the unity of the outreach of the decade of discipleship, evangelism and mission. It is in danger of building this decade on sandy ground. It begs the question, what are we proclaiming about the Christian life? What are we telling children about what makes a Christian. It’s imperative for the glory of the Lord Jesus and the unity of the mission, that Gafcon truly, with humility and courage, resets these liturgies and practices to reflect the true biblical and Reformed Evangelical nature of Anglicanism.

Another tension within Gafcon that has potential to fragment it is the unresolved issue of the ordination of women to the presbyterate and to the office of a bishop. This tension was recognized, by implication at least, in article 12 of the Jerusalem Declaration 2008, where it states ‘we pledge to work together to seek the mind of Christ on issues that divide us.’ In its 2009 commentary on the Jerusalem Declaration, Gafcon made further comment on diversity within it. In Clause 13 ‘Freedom and Diversity’ (particularly section 3), whilst the ordination of women is not explicitly mentioned, it seems to recognize that for some in Gafcon, this is a secondary issue, but for others a primary issue, and that they might just have to live in ‘..unremitting love in unresolved tension…’ about it.

The Kigali Commitment, however, seems to suggest that Gafcon has made its mind up now. Its statement on ‘Gafcon women’ seems to be a rejection of the biblical complementarian view of women’s ministry, and an acceptance of the egalitarian view. It reads, ‘we will affirm and encourage the vital and diverse ministries, including leadership roles, of Gafcon women in family, church and society, both as individuals and as groups.’ Whilst it is very much to be welcomed that women are to be encouraged in their various ministries, including being trained to the highest levels of Word ministry for appropriate leadership roles in their church, evangelism, and discipleship, does the Gafcon leadership intend this to be read as including ordination to the presbyterate and to the office of bishop? If this statement does intend that to be read into it (as it seems to do), then it has created and will continue to create a huge tension within Gafcon.

As it is, Reformed Anglican Evangelicals, will rightly point out that this is no secondary matter. This is a matter of obedience to the plain teaching of Scripture. Furthermore, many of them have suffered discrimination from liberal Provinces and bishops, and sometimes from Charismatic bishops for standing on this biblical complementarian view. The Kigali conference rightly highlighted how western secular values have infiltrated the church concerning sexual matters, but many would contend that the same is true of women’s ordination. With both issues, the plain teaching of Scripture is being ignored or set aside as secondary by those advocating these changes to Anglicanism. This too will hamper the fellowship, mission and development towards a more biblical orthodox Anglicanism, that we so desperately need.

So, whilst the GAFCON IV Kigali gathering was, in the main, a heart-warming, biblical call to worldwide Anglicanism, nevertheless, it needs to go further. It needs to ask member Provinces to put their own house in order, in line with the call that Christ rules his church through his Word. When, in Revelation 3:20, Christ stands at the door and knocks, he’s not addressing non-Christians, he’s addressing a lukewarm church, calling it to repentance and to open its door that Christ may fill every part of it. This is how we truly become spiritually richer, not by side-lining his word, or watering it down to suit our culture, but by inviting him to be Lord over every area of his church, its teaching, its liturgies, its leadership, its discipleship and its mission.