Victimhood: the condition of having been hurt, damaged, or made to suffer, especially when you want people to feel sorry for you because of this or use it as an excuse for something. (Cambridge Dictionary)

Introduction

Liberal Protestantism has in recent times developed a theology, especially in the areas of socio-political discourse of victimhood. It can be summarised simply as “Jesus was a victim, and he identifies with all in society who are victims”.

I believe this simplistic meme leads to an incorrect understanding of Jesus’ mission, and it can have a disempowering, paralysing effect on people. Many people, conscious of their socio-economic status, compare themselves with those better off and develop a mindset of victimhood. This often leads to self-pity and the impulse to make others feel guilty for their situation.

I will first attempt a brief analysis of contemporary culture, and secondly offer what I believe to be a Christian response centred on a biblical anthropology and personal responsibility.

Was Christ a victim, and if so, in what sense was he a victim?

There is no Biblical Greek or Hebrew equivalent for our word ‘victim’, it does not appear in the Bible. The English word victim (from French victime) only came into usage to describe Christ in the mid 17th century – specifically as victim of our sins, and then later to describe people who suffered from criminal acts. Theological reflection in earlier times saw Jesus as a victim in a metaphorical sense and in the language of sacrifice – he was the lamb of God, slain for us. It was a way of describing his vicarious suffering. Jesus laid down his life voluntarily – he was not a victim in the sense of being subjected to the will of others non-voluntarily. Everything he did as a man he did freely; John records several times that Jesus indicated his voluntary and complete self-sacrifice, “I lay my life down and can take it up again anytime”.

This means that the only Christian “victimhood” must be vicarious (1 Peter 4:1ff, 2 Timothy 2:11-12) and not any other form (1 Peter 4:15).

Of course, we can be victims in the sense of suffering because of the actions and bad motives of others who wish to do us harm; we can be victims of crime, greed, drunken drivers, rapists or racists. We can also bear the brunt of unjust socio-economic and political structures. Furthermore, as Christians we have a duty to stand against all victimisation, oppression and injustice in society.

However, the concept of a victim group based on a perceived ‘victimhood’ has become a basis on which many people construct their identity. I believe the foundations of this in contemporary culture are to be found in the influence of cultural Marxism.

Marxist thought sees the problem of suffering in purely structural terms. Reality is defined only in materialistic and economic terms. Society is defined only in terms of power relationships; it consists of two groups of people – oppressor and oppressed. The origin of suffering is this social dynamic. Inherent also is the idea of utopia – if oppression can be removed then we would have a utopian society. The black and white defining the nature of the moral issue – the oppressed as the only ones who really suffer- leads ineluctably to the demonization of one group – those who are labelled as the oppressors. Another dynamic is introduced when we identify victims of suffering and oppression with Christ’s suffering and oppression. There is the danger of sanctifying them purely on the basis of their existential experience and allowing them to mask self-pity as goodness in order to elicit action or solidarity with their particular cause.

This is seen particularly in the contemporary western ‘cancel culture’ in which group identity is based on victimhood. Mary Eberstadt offers us this definition of cancel culture,

Cancel culture basically says – you cannot understand me, and you are committing an injustice against me unless you are part of my victimised group.

Each self-identifying ‘victim group’ (eg women, gays, transgender, black) generates an ever evolving set of boundaries to define their group identity. Transgression of these boundaries leads to a public shaming and a scapegoating – even a demonization. Eberstadt notes that there is no room for redemption in this culture.

Biblical theology uncovers a much deeper, more fundamental and more complex answer to the problem of suffering. Its’ origin is of course firstly spiritual (which manifests in social structures but does not originate there). It cannot be understood without reference to the transcendent creator of the universe and his purpose in creating human beings. In Genesis Chapter 3, Adam and Eve disobey God and sin enters the world: their actions have consequences, one is the knowledge of good and evil and also the potential to do either good or evil to others. Sin, or disobedience to God has resulted in suffering entering the world as human potential. Another consequence is mortality and struggle. Thus, suffering is integral to the structure of self-conscious being. It is not primarily the consequence of sociological or political oppression (but becomes bound up with social and political structures as the whole creation is in bondage to corruption – Romans 8:21).

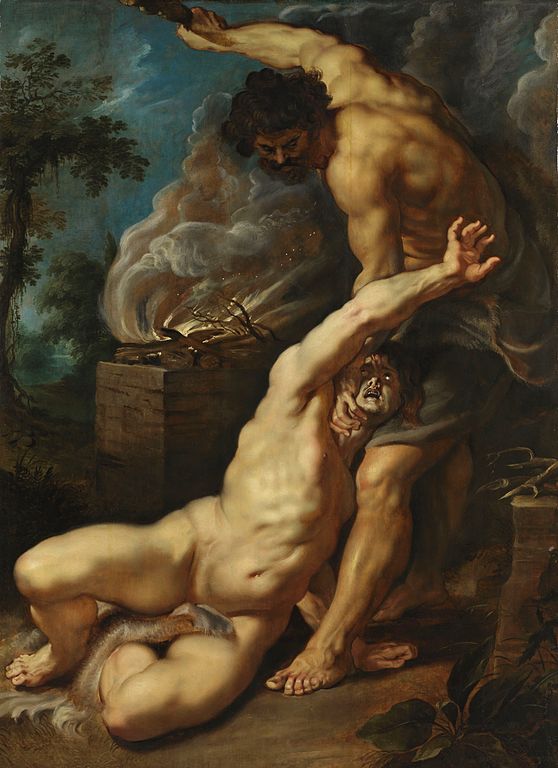

In the narratives that follow Genesis 3, the theme of human sin and its consequences are explored more fully. In several of these stories – Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau, Joseph and his brothers – we find two attitudes to reality that are highlighted. Professor Jordan Peterson has offered some powerful psychological insights that can help us observe these attitudes more clearly.

Cain and Abel: Genesis 4:1-16

Abel’s offering is accepted by God and he is rewarded. Cain is rejected. Cain reacts with disappointment (his face has fallen). Generally, the Bible does not suggest offerings operate automatically, but God’s acceptance of them is dependent on the heart attitude of the person making the offering. Cain’s heart attitude is revealed by his reactions – he resented his brother and resisted God’s instruction. God tells Cain that his destiny is in his own hands, but resentfulness, anger and bitterness is controlling him, affecting his relationship with reality. He has projected his problem onto someone else instead of seeing it within. The epistle of 1John (3:12 to 15) expands on Cain’s behaviour and attitude; “…he practised unrighteousness and hated his brother”– he allowed sin to overwhelm him and eventually murders his brother.

In the story God tells Cain “…if you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at your door. Its desire is for you, but you must rule over it.” (Genesis 3:7) Hereby indicating that he must take responsibility for his life and the condition of his heart – he cannot blame others. Cain attempts to evade his responsibility “…am I my brother’s keeper?” (v9). Victimhood passively expects others to take responsibility for our lives.

Jacob and Esau: Genesis 25:19-27:44

Esau’s attitude and behaviour parallels that of Cain. He is called ‘unholy’ in Hebrews 12:16,17; this because he treated his spiritual inheritance as the firstborn as something he could sell – thus despising his inheritance and his calling. To despise what God has given us, even if we are born into very deprived conditions is to reveal an unholy attitude and without repentance, that person is in danger of both falling into bitterness and losing everything. The other side of the coin is to take for granted or even despise the priviledged position, the talents or the material wealth we have been blessed with, and misuse it.

Joseph and his brothers: Genesis 37-50

Likewise, Joseph receives preferential treatment. Texts throughout Genesis hint at his privileged status, even although he was the youngest brother. Genesis 37:12 is the first of these hints, which become clearer in later chapters. He was given a special coat by his father Jacob. This signified a special role – a status above his brothers, which was counter cultural, and his brothers would have continually seen this sign. His brothers hate him and conspire to murder him.

In these patriarchal narratives we see two views on reality contrasted – one person sees the worlds darkness, unpredictability, disadvantage etc (bible does not say that its good) and is angry and resentful. There is a consequent desire for revenge which leads to various actions like murder (Cain and Abel) plotting (Jacob and Esau) or selling into slavery (joseph and his brothers). The election by God of specific people causes offence and resentment, also the apparent unequal rewarding by God is also seen as unfair.

Jesus himself examines these attitudes in several parables:

Parable of the Talents: Matthew 25:14ff “well done, good and faithful servant” – these words of praise serve to highlight a key teaching in the parable that what matters is not how much you are given or how much you make, but faithfulness in using your potential and utilising your gifts. Those who are privileged in some way have a responsibility to those who are deprived. This is echoed by Paul who calls on those who are materially better off to be generous, sharing what they have and doing good (1 Timothy 6:5).

Parable of the Rewards: Matthew 20:1ff This parable of the labourers in the vineyard is told by Jesus in the context of Jesus’ prior challenge to the rich young ruler to give up everything. Peter, apparently in a bit of a self-pitying way, has asked what rewards the disciples will get for their own self-sacrifice. The parable seems to be a gentle rebuke to Peter. In the parable some workers protest the fact that the master gives all the same reward, despite the fact they worked longer hours. Jesus judges the man as having an ‘evil eye’. In other words, he judges God’s actions as unjust, because of his own self-interest, instead of being thankful for what he has – little or much. Jesus points out that God as owner of all is entitled to do what he chooses with what belongs to him. Here also we see that justice is not always self-evident. Biblical justice is God’s justice – it cannot be understood without relationship to created purpose (am I not allowed to do what I please with what belongs to me?).

Luke 12:13-15 Here a man asks Jesus to mediate in a dispute about inheritance (traditionally the role of a rabbi) He refuses to pass judgement and highlights the fact that covetousness is the motivation underlying some demands for justice in interpersonal affairs (v15). Jesus is more concerned with attitudes of people than with the question of whether or not a person gets what is “rightfully theirs”

Victimhood is not a Christian virtue and is a breeding ground for self-pity, self-centredness, covetousness, envy and resentment. It reminds us that that the world is not divided into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people, but the line dividing good and bad runs right through every one of us. Sin blinds us to our own corruption and we project it onto others (Why do you see the speck in your brother’s eye but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Matthew 7:3).