Engine against the Almighty, sinner’s tower,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear,

The six-days world transposing in an hour,

A kind of tune, which all things hear and fear;

Today I hope to speak a bit about prayer, poetry and hymnody.

Dennis Lennon comments about Herbert’s “a kind of tune”:

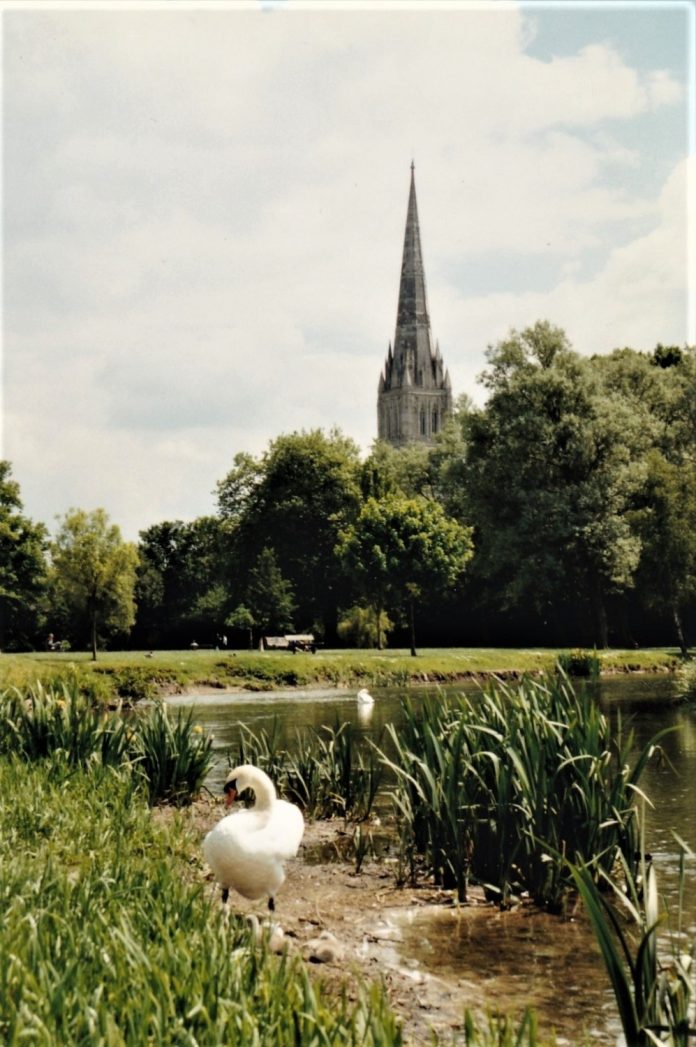

Our teacher has music on his mind. In the previous metaphor prayer is the world “transposing” into a different key; now it is a “kind of tune”; universally heard and “feared,” as respect or as dread. His biographer mentions that Herbert’s “chiefest recreation was music, in which heavenly art he was a most excellent master, and did himself compose many divine hymns and anthems which he set and sung to his lute or viol. Twice a week he walked to Salisbury to attend worship at the cathedral, occasions he referred to as “his heaven on earth.”

I imagine him walking along the lanes and across the meadows from Bemerton to Salisbury, hearing “a kind of tune” coming out of the cathedral – bells, orchestras, organ, choirs, chanting and singing. Did the experience suggest to his mind prayer as something already on the move in the air around him, inviting his prayer? …

Twice, I confess, my wife and I have made the pilgrimage between Salisbury and Bemerton, stopping midway for cream tea at the Old Mill at Harnham. But I must also confess that I do not find George Herbert’s poetry “sings” well in a congregational setting. It’s no accident perhaps that few of his lyrics make it into Anglican hymnals, and perhaps his best hymn, “Let All the Earth in Every Corner Sing” is good but not great, an emerald perhaps but not a diamond.

Why is this? Well, for one thing, English church music of the sort Herbert trekked to was an aristocratic art, with evensong anthems and plainsong for cathedral choirs. Herbert’s lute and viol were lovely instruments for Elizabethan quartets or a chamber orchestra with solo voices, but not for farmers gathering on Sunday morning. Herbert was himself an aristocrat, and while he delighted in “outlandish” proverbs and riddles, his poetry is dense; like “Prayer,” one has to stop and meditate on it rather than sing it through.

Secondly, while the English Prayer Book owes much to the genius of Thomas Cranmer, congregational singing was straitjacketed by the Calvinist conviction that only biblical texts, the Psalms in particular, were appropriate for Sabbath worship, and congregations for two centuries were nurtured on the jejune metrical versions of Sternhold and Hopkins. For this reason, there was a musical imbalance between the lyrics of the “sweet singer of Israel” and the “hymns and spiritual songs” of the New Testament church (Ephesians 5:19).

Lennon comments further:

There is no question where the cosmic hymn originates: at the empty tomb. As though the angel struck a tuning fork and stood it on “the great stone” rolled back, sending its note singing through all of space and time: Christ is risen! Prayer is “a kind of tune which all things hear and fear” is first and last Christ’s prayer. He stands in the midst of his earthly family gathering us up into his worship offered eternally to the Father.

The great age of English hymnody was waiting for poets of a more democratic and non-conformist temper. Their hymnody was not only better suited to congregational singing, but it introduced Gospel themes about Christ’s birth (“Hark the herald Angel sings!” – Charles Wesley), death (“When I survey the wondrous Cross” – Isaac Watts), Resurrection (“He is Risen” – Cecil Frances Alexander), and Ascension (“Jesus Shall Reign Where e’er the Sun” – Watts again), the Great Commission (“Shine, Jesus Shine – Graham Kendrick), and the Church Triumphant (“Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken, Zion City of Our God” – John Newton).

None of which is to say that George Herbert’s poetry may not touch the heartstrings of his readers. I have already mentioned “Love III” as perhaps the greatest religious lyric ever. Another example of Herbert’s inner tunefulness comes in “The Flower,” which celebrates the rebirth of nature, of the soul, of poetic inspiration, and of eternal life:

How Fresh, O Lord, how sweet and clean

Are thy returns! even as the flowers in spring;

To which, besides their own domain,

The late-past frosts tributes of pleasure bring.

Grief melts away

Like snow in May,

As if there were no such cold thing.

Who would have thought my shriveled heart

Could have recovered greenness? It was gone

Quite under ground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they have blown;

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

These are thy wonders, Lord of power,

Killing and quickening, bringing down to hell

And up to heaven in an hour;

Making a chiming of a passing-bell,

We say amiss,

This or that is:

Thy word is all, if we could spell.

O that I once past changing were;

Fast in thy Paradise, where no flower can wither!

Many a spring I shoot up fair,

Offering at heaven, growing and groaning thither:

Nor doth my flower

Want a spring-shower,

My sins and I joining together;

But while I grow to a straight line;

Still upwards bent, as if heaven were mine own,

Thy anger comes, and I decline:

What frost to that? what pole is not the zone,

Where all things burn,

When thou dost turn,

|And the least frown of thine is shown?

And now in age I bud again,

After so many deaths I live and write;

I once more smell the dew and rain,

And relish versing: O my only light,

It cannot be

That I am he

On whom thy tempests fell all night.

These are thy wonders, Lord of love,

To make us see we are but flowers that glide:

Which when we once can find and prove,

Thou hast a garden for us, where to bide.

Who would be more,

Swelling through store,

Forfeit their Paradise by their pride.

Whatever one’s musical taste, Herbert’s depiction of prayer as a cosmic tune is an essential message for our age. I sometimes think as I observe people today importing music through their iPods: Do they ever sing-along, do they hum a tune or whistle it out loud? Is the tune of creation and glory getting through? I am not so sure.

Lennon concludes of Christ’s new song:

These are creation’s sudden and surprising gifts in a world turned praising toward her Lord, uttering her “kind of tune which all things hear and fear.” But a steady bombardment of irreverence and derision threatens to overwhelm her canticle, or rather, our ability to detect it. She looks to us for our partnership, indeed for our leadership in the work of praise….

The beautiful God should be celebrated beautifully. It was a war-cry in the early church that “Everything good, everything beautiful belongs to us (Justin). Beautiful things whisper their “kind of tune,” their witness to the loveliness of their Lord. It is part of our stewardship to promote and celebrate the beautiful as pointers to God and to be on our guard against the cult of ugliness and pessimism out which no canticle rises to God.

On Day Nine, we move to the next stanza and pick up on the beautiful “tune” in terms “Softness and peace and joy and love and bliss”