We were asked in 2017 to undertake a qualitative research study into child sexual abuse by clergymen – it was exclusively perpetrated by ‘men’ – in the Diocese of Chichester.

We were asked specifically to look at the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of what happened, rather that the ‘who’, ‘what’ or ‘when’. This involved examining patterns surrounding the abuse itself alongside features of the organisation which may have contributed to or maintained it.

One of us (Yvonne) interviewed at length 17 individuals including survivors, professionals and senior members of the diocese. Additionally, three individuals responded to the questions by email.

To our knowledge, no other religious organisation in England has ever commissioned such a study, so we saw the request as a positive indication from the diocese of its intention to learn from the past. The final report is shocking, and, at various points, heartbreaking.

Abuse outside the family

There are significant implications in this research for social care practitioners, who now routinely must address new challenges in child protection, many of which occur outside the family, until now the primary site for professional intervention. There are clear resonances here with Carlene Firmin’s work on ‘contextual safeguarding’; see her TedxTalk for more information.

In our view, one of the most important lessons to be learned from the research emerges from the accounts of those children and young people who survived the abuse and who can now talk about it. That is why we were encouraged when we read the following in the introduction to our report from Chichester Diocese:

‘In particular, the Diocese wishes to thank those victims of abuse who agreed to be interviewed, reliving very painful experiences in order that those responsible for preventing abuse in church now can learn lessons from the past’.

Social workers, teachers and others working with children need to take account of the unabridged recollections of survivors of sexual abuse. But ‘listening to survivors’ can end up little more than a hollow mantra unless their experiences are used explicitly to frame policy and practice. This is why one of our key recommendations is that the findings are discussed fully, honestly and openly with all concerned in the diocese but especially with the survivors of the abuse.

Listening with compassion

If their experiences are actively listened to with compassion, it not only helps them feel empowered, it also potentially supports them to move on by strengthening their resilience.

Each interview was conducted by Yvonne at a gentle pace, so that the individual would feel safe and that their views were taken seriously. This is particularly important for those who had not been able to speak out about their abuse for many years. As one survivor put it:

‘There wasn’t one person I was able to talk to about what was happening to me. It was only just before he left that I realised what had been happening to me. I didn’t know. It didn’t dawn on me until years later. I didn’t have any words to express it. I couldn’t describe it.’

Forms of grooming

Patterns of grooming in the diocese had similarities with other forms of sexual abuse, but there were also differences, some of which were chilling.

In our research we heard that the sexually abusive clergymen sought to gain the child’s trust in devious and calculating ways.

For example, we heard that they would sometimes reserve a special pew for their family, or they would take the child on special trips and holidays, and sometimes they bought them expensive clothes.

With older children, we heard that some abusers successfully courted the ‘rich and famous’ – also to impress the family. We were told that alcohol was used to lower defences and to treat the young person as an ‘adult’. Sexual innuendo and ‘jokes’ helped develop a group identity, the aim of which was to normalise the abuser’s sexual activity.

We heard examples of how the paraphernalia of the Church – the incense, the elaborate liturgical garments, the rituals – were recruited by sexually abusing clergy to create an aura of respectability as well as deliberately to use their perceived omnipotence to strengthen obedience. Shrouded in a cloak of secrecy, this also reinforced the impression in the child’s mind that no one would believe them if they decided to tell someone. Isolating children through fear is a ploy used by many sexual abusers but it is a particularly malign one when used by a member of a religious or faith-based community.

The final insult we heard about was when a young person was told by the priest that what was happening to her/him was the result of her/his own sin and ‘bad behaviour’ and that what was happening to them was part of a process of purification. At this point, as one of the individuals interviewed put it, ‘You can’t say No to God’. This chilling phrase became the title of our report. Abusers in powerful positions have always used their status to ensnare victims but these examples of how some senior members of a religion based upon love, peace and hope wielded their power and influence are especially dispiriting.

Listening and learning

In conclusion, we were encouraged to read the following sentence in the diocese’s introduction to our report:

‘The suggestions contained in both this report and others offer food for thought, for the wider church and not only for this Diocese, and indeed for other organisations’.

By listening to and learning from survivors’ experiences, something social work has led the way on for some years now, practitioners are in a strong position to recognise signs of abuse and find ways to support victims to disclose what is happening and protect them as well as gain the trust of survivors in order to help and support them.

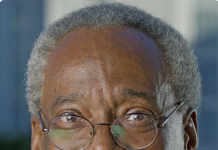

David Shemmings is emeritus professor of child protection research at the University of Kent and visiting professor at Royal Holloway. He specialises in relationship-based practice. Yvonne Shemmings runs an attachment and relationship-based practice training programme with David and is an author, researcher and trainer.