December 9, 2025

Dear Bishops,

I am grateful for the letter issued by the College of Bishops following the recent meeting at Christ Church Cathedral. Its tone is sober, prayerful, and unmistakably shaped by the Church’s habits of repentance and humility.

In a season when many institutions reach first for self-protection or silence, you chose confession. That choice deserves respect.

The letter reflects the difficult season in the life of the Anglican Church in North America. It acknowledges serious shortcomings in relationships, courage, attentiveness, and care. It acknowledges a loss of trust in the College and recognizes confusion caused by vague and (apparently) unfinished disciplinary canons.

Grounded in Scripture, the Daily Office, and the Advent hope of Christ’s light, the letter seeks forgiveness, offers intercessory prayer for all affected—victims and accused, and reaffirms the sacred calling of the episcopate.

But then it ends. It seems to stop short of helping tens of thousands of Anglicans understand what we can do, what next steps to take, and where we are heading.

Repentance is always the right beginning, especially in Advent. It was the first word spoken by John the Baptist and the first word preached by our Lord. Advent places that call before us again each year. A Church that forgets repentance forgets who she is. For that reason alone, the letter matters, and I want to say plainly: thank you for beginning where the Gospel begins.

Yet, when I read the letter, I found myself encouraged but unsettled.

With due respect to your office, I submit that because repentance is such a holy and weighty matter, it must be allowed to do its full work. Repentance is not meant to leave leaders bowed inward, weighed down by guilt or immobilized by shame or sorrow. In the Christian tradition, repentance opens the way forward. It leads to amendment of life—a new resolve, new clarity, new obedience.

What many might long for is a glimpse of the path ahead.

Bearing Too Much?

One of the most striking features of the letter is the weight the College is carrying. The bishops speak collectively of shortcomings, failures of courage, lapses in attentiveness, and loss of trust. Such honesty is rare and honorable.

But is the College assuming more responsibility than any one body can reasonably bear, much less repair?

Not every challenge facing the Anglican Church in North America is personal or relational. Some are structural. Disciplinary canons can be clarified—and should be—but jurisdictional overlap, blurred authority, and inherited complexity cannot be resolved by repentance alone. They require assessment, repair, and in some cases, redesign.

And when leaders take all the blame upon themselves, they might unintentionally flatten the problem—and in doing so, leave deeper causes untouched.

A Cautionary Tale

Recent wildfires in California offer a sobering analogy. When the fire finally erupted into an inferno, it was discovered that the disaster was not caused by a single spark alone. Equipment was under repair. Reservoirs were depleted. Hydrants were dry. The conditions for catastrophe had been set long before the flames were visible.

Leadership in such moments is not primarily about apology. It is about diagnosis, audit, and repair. Naming what failed structurally—not just relationally—and then fixing what can be fixed.

Many of us in the Church are hoping for that same clarity.

Sword and Trowel

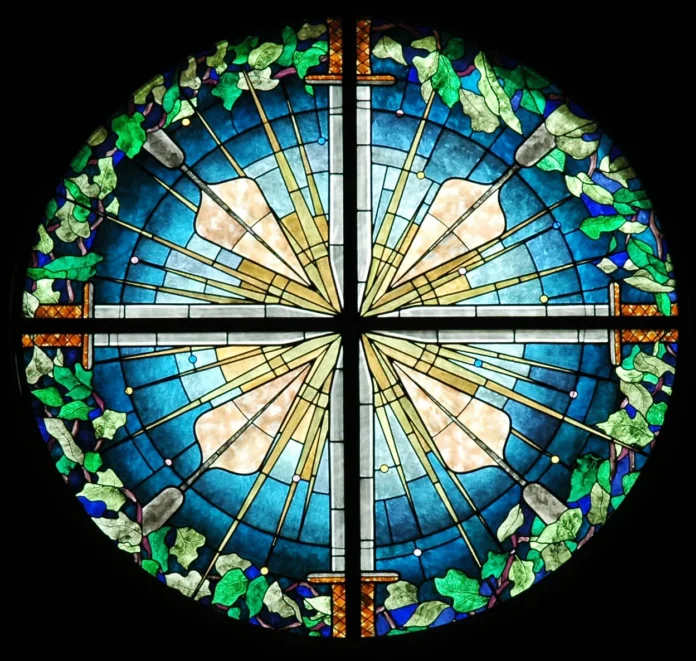

The bishops met at Christ Church Cathedral in Plano, a space I know very well. I think it is one of the most beautiful places for worship. The photo of the gathering with purple in every pew did my heart good!

Did you happen to notice the stained-glass window overlooking your proceedings? It is the featured image for this article.

The inspiration for the window is drawn from Luke 14 and Nehemiah 4. Jesus is telling his disciples about the job requirements. They will be like a builder building a tower or a king going off to war. The window features trowels and swords for their twin tasks, which I think are your twin tasks too: to build and to defend.

The image reaches back further still, to Nehemiah, where those repairing Jerusalem’s walls worked with a trowel in one hand and a sword in the other.

That was Nehemiah’s requirement.

They built.

And they defended.

At the same time.

They worked.

And they kept watch.

At the same time.

That window was designed to inspire courage and clarity. It reminds us that the Church’s leaders are called to both build and guard—to repair what is broken and to protect what is true.

Read it all in The Anglican