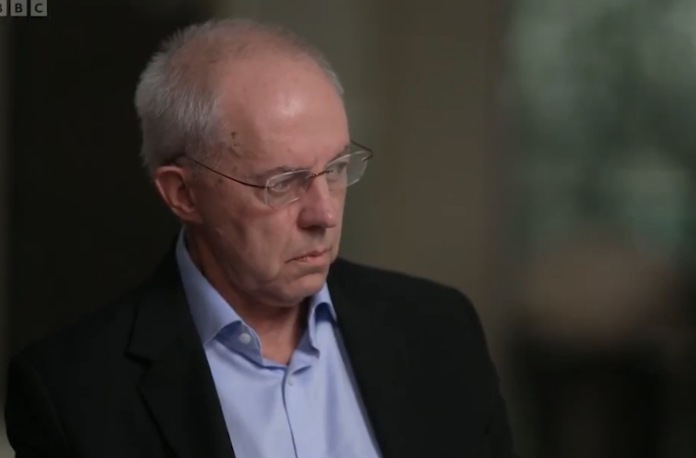

If the former archbishop of Canterbury hoped his self-abnegation on the BBC might salvage what was left of his reputation, he was wrong.

Overwhelmed. When Justin Welby looks back on the early months of his tenure as archbishop of Canterbury, that is the word that comes to his mind. In his first interview since his resignation, Welby told the BBC that he was shocked by the torrent of safeguarding cases that flooded across his desk when he entered Lambeth Palace in 2013: historic cases, recent cases, disputed cases; bishops, deans, archdeacons and priests accused or suspected of abusing choirboys, parishioners, even their fellow clergy. “Safeguarding was the crisis I hadn’t foreseen – I didn’t realise how bad it was,” Welby said. The scale of the problem was why, Welby now says, he failed to adequately respond to the case that would ultimately bring his tenure to an end 11 years later.

An independent investigation into the abuses of John Smyth – which were first reported to the Church of England (C of E) in summer 2013, months after Welby took office – was published last November. The Makin review criticised Welby for not ensuring those early allegations reached the proper authorities. Within days of its publication, Welby resigned, becoming the first ever head of the Church to step down in disgrace.

In the BBC interview on 30 March, Welby apologised: “I am so sorry for what I failed to do [and] for what the Church did do with John Smyth… I am so sorry that I did not serve the victims and survivors… as I should have done, and that’s why I resigned.”

He attempted to explain, if not justify, his failures. He was new and inexperienced in the job when the accusations came across his desk. The national Church then had a single, part-time staffer for safeguarding (under Welby, the team grew to almost 60). The rules said it was the local bishop in Ely, not Canterbury, who should take the lead. The police asked him to hold off while they looked into the case themselves. He was distracted by another scandal that was going through the courts and seemed more pressing. “It was an absolutely overwhelming few weeks,” Welby said. “That’s not an excuse… The reality is, I got it wrong. As archbishop, there are no excuses for that kind of failure.”

If the former prelate hoped his self-abnegation might salvage what was left of his reputation, he was wrong. The response to the interview has mostly been anger at what many victims see as an attempt to shift the blame. Some continue to believe Welby is obscuring the extent to which he knew about Smyth’s abuse before 2013, given he had attended camps with Smyth in the 1970s.

Smyth was perhaps the most prolific abuser in the modern history of the Church of England. Around 130 teenage boys, many of them groomed while attending evangelical summer camps co-led by Smyth, were sexually, psychologically and physically abused by him. After this was discovered in 1982 by the trust that ran the camps, Smyth was quietly pushed out. But the trust chose not to pass on what they knew to the Church authorities or the police. Smyth went on to set up camps in Zimbabwe, where he began abusing boys again.

The Makin report concluded that Smyth’s crimes were an “open secret” among many in the conservative-evangelical wing of the C of E. But it took a Channel 4 News documentary in 2017 to expose him. Survivors continue to demand every clergy member named in the report resigns or be disciplined. The Church has identified ten – including a former bishop of Durham and George Carey, archbishop of Canterbury from 1992 to 2002 – whose involvement in the “cover-up”, as the report calls it, warrants formal disciplinary proceedings.

Read it all in the New Statesman