I have a dream for the Anglican Communion. It is a beautiful dream, of a fellowship of autonomous Anglican churches in diverse regions across the globe, from many different nations, languages and people groups, who are united in their common commitment to the apostolic gospel. These Anglicans are in full communion with one another, bound together by bonds of affection and mutual interdependence. They share a common Anglican story, stretching back to St Augustine’s mission to England in the sixth century, and they express and inhabit the gospel in a common way, rejoicing in the great Anglican texts of the Reformation such as the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion and the Book of Common Prayer. In my dream, these Anglican provinces delight in their gospel partnership and their common faith, mission, and discipleship. It is nothing less than a foretaste of heaven. This is the Anglican Communion ideal. It chimes closely with the classic statements on Anglican identity made by the Lambeth Conferences of 1920 and 1930, and with the standard Anglican textbooks of the twentieth century.

If, God forbid, sin and error invade this Edenic picture, in my dream there is a coherent biblical method for dealing with any Anglican province which departs from the gospel essentials of faith and holiness. First an erring province would be called lovingly to repent. Next, if unrepentant, they would be disciplined and temporarily removed from Anglican fellowship and decision-making. Finally, as a last resort, a recalcitrant province would be expelled from the Communion and their place taken by gospel-centred Anglicans from that region. In this way, harmony is restored and the dream continues.

If you share this dream for the Anglican Communion, I say WAKE UP! It is a wonderful dream, but a dream only. This Anglican Communion does not exist in the real world. It is a mirage, a figment of our imagination, a fantasy. If it ever existed, it certainly exists no longer. It is time to let go of the old Anglican textbooks, written by theorists, and face facts. We need to wake from our stupor and look at the Anglican Communion with clear-eyed realism.

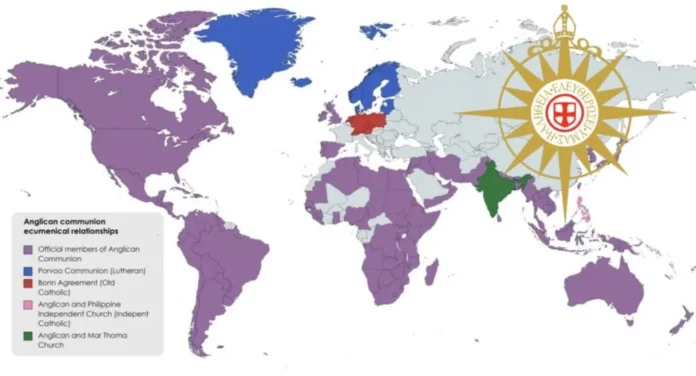

IASCUFO is team of Anglican theologians helping the Communion to think in new ways about our ecclesiology and interprovincial relationships. Its membership is diverse, drawn from Australia, Barbados, Brazil, Burundi, Canada, Chile, Congo, Egypt, England, Eswatini, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Singapore, the United States, and Wales. IASCUFO has been set the challenge of offering practical proposals for reimagining and renewing the structures of the Anglican Communion. Its ambition is not to turn the clock back to an idealized, imaginary Anglican past, but to look current facts firmly in the face. We are no longer living in the 1920s and 1930s. We need practical, achievable, real-world proposals for Anglican life in the 2020s and 2030s. This is not mere pragmatism, however. The Nairobi-Cairo proposals build a serious ecclesiological case for a new Anglican Communion structure. They open a pathway to global Anglican renewal which is deeply theological, rooted in the Anglican tradition while also borrowing crucial insights from the world of ecumenism.

Faced by the undeniable evidence of deep divisions in the Anglican Communion today, four main responses are possible.

1. Keep Dreaming

One option is to keep pursuing the old dream for the Anglican Communion. This has been urgently expressed, for several decades, through proposals like To Mend the Net (2001) and Repair the Tear (2004), which called for repentance, discipline, and the restoration of godly order and authority. The Windsor Report (2004) offered a practical method for building the dream, through an Anglican Covenant to be adopted by all the provinces of the Communion, but the proposals collapsed, rejected by progressives and conservatives alike.

What have we learnt from the failures of the last 20 years? That the dream will never be fulfilled, certainly not in our lifetimes. The Windsor proposals had good potential, in theory, but crashed in practice. The likelihood of the whole Anglican Communion covenanting together is zero. It will not happen, at least not for the foreseeable future. Those who are still hoping for erring provinces to be disciplined or excluded will be waiting a long time. If the success of the ‘instruments of Communion’ is to be measured by their ability to exercise discipline, then the instruments have failed. But that is not a fair test, because the old instruments were never designed in this way. For Anglican dreamers to go on banging their heads against a brick wall, trying to set the clock back to pre-2003, is a waste of energy. It is tilting at windmills. It is living in an illusion.

2. Keep Pretending

Another option is to pretend that Anglican unity already exists. Anglican adiaphorites see every dispute as a secondary or tertiary issue, never a core gospel concern. Divisions are downplayed as ultimately insignificant, perhaps even a positive expression of our glorious Anglican comprehensiveness, certainly not serious enough to disrupt our relationships or break our eucharistic fellowship.

The Nairobi-Cairo proposals deliberately eschew an adiaphoric approach. The IASCUFO report is frank in its analysis (§41-42) that the current crisis in the Communion is centred upon the blessing of same-sex relationships which, on both sides of the dispute, are viewed as a matter of deep significance involving sin and offence to God. It helps no one to pretend otherwise.

3. Keep Separating

A third option, in face of these deep divisions, is for Anglican provinces to separate from one another completely and absolutely. Most radically, we could burn down the Anglican Communion, dismantle all the old structures, and start again. IASCUFO has begun to consider what would happen if provinces ask to be removed from the Communion. There is an existing process for welcoming a new province into the Communion, but no process for bidding farewell to a province wishing to depart.

The recent collapse in corporate Anglican identity has led some provinces to break eucharistic fellowship or refuse to send delegates to global Anglican gatherings. But no province—not even the more bullish members of the GAFCON movement like Nigeria, Uganda, and Rwanda—has left the Anglican Communion or hinted that they plan to do so. That day might come, but there are no signs of it yet.

4. Keep Engaging

The final option is for Anglican provinces to keep engaging with each other, despite their deep disagreements, as generously as possible. We are never short of identifying ways in which the Anglican Communion is failing. That analysis is important, but the question also needs to be flipped around and asked the other way. What is good about the Anglican Communion? What can we do better together than apart? How would we be poorer if the Anglican Communion is dismantled? Surely no one, even the grumpiest curmudgeon, can see nothing at all good in the Anglican Communion?

To reiterate, Anglican engagers are not adiaphorites! A policy of generous engagement does not pretend that all is rosy or that disagreements are secondary, but it does—in the best ecumenical fashion—seek to build on what is good. Anglican provinces may now have grown so far apart in our understanding of Christian faith, that united evangelism, discipleship and theological education is impossible. But does that mean we should stop talking to each other? Or that we have no common cause in areas such as creation care, safeguarding, domestic abuse, assisted dying, artificial intelligence, abortion, human trafficking and modern slavery, to name just a few?

To take an historic parallel, the doctrine of justification by faith alone in Christ alone is not a secondary issue but drives at the very heart of the gospel. It is one of the chief reasons that ecclesial separation was necessary at the Reformation between evangelicals and Roman Catholics. But does that mean evangelicals and Roman Catholics, in their separate churches, should have no relationship, never meet, never pray together, never share resources, never stand on the same platform? On the contrary, we can hold firmly to gospel essentials and still engage across the divide.

Binary approaches to Anglican ecclesiology are naïve—that Anglican provinces must either be united or separated, either walking together or walking apart, either sharing ‘full communion’ or ‘no communion’. By reimagining the Anglican Communion, at least in part, in ecumenical terms, we discover a richer range of options. To borrow a classic ecumenical idea, it is good to seek ‘the greatest degree of communion possible’ between divided Christians, even if that communion is severely restricted. This ecumenical sliding scale is messy, and does not suit Anglican dreamers, but it is realistic.

So then, while powerful centrifugal forces are driving Anglican provinces further apart, what changes to the structures of the Anglican Communion are necessary to facilitate our continued engagement? Three significant ideas are found at the heart of the Nairobi-Cairo proposals, which are new ways of conceiving the global Anglican project.

1. Embrace Covenantal Renewal

The 2004 Windsor proposals for an Anglican Covenant failed to win sufficient support, partly because the covenant was to be imposed upon the whole Communion, which some provinces viewed as theologically coercive. Now the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches (GSFA)—formally recognized by the Anglican Communion since the 1990s—has reimagined the covenant as an invitation to closer Anglican relationships on a voluntary basis. GSFA’s covenantal structure was inaugurated at its assembly in Egypt in May 2024, with nine Anglican Communion provinces as full covenanted members and others likely to join soon. GSFA have consistently affirmed that they have no intention of leaving the Anglican Communion.

The growing influence of GSFA explicitly sets the context for IASCUFO’s deliberations (§7-8). It would be possible, of course, for the Communion to carry on as if nothing has changed, or to hold GSFA at arm’s length. The IASCUFO report does the opposite. It deliberately welcomes the role of GSFA in helping the Anglican Communion to discern ‘doctrinal and ethical truth’, and highlights GSFA’s hopes ‘to see the Communion articulate afresh with vigour the catholic and apostolic faith and order of the Church as a renewal of her mission’ (§56). It also publicly praises GSFA, and its covenantal commitments, for enriching relationships between the provinces of the Anglican Communion and global Christianity more broadly (§68-69). GSFA is not treated as a competitor to the Anglican Communion but, on the contrary, as an essential driver of Anglican theological renewal.

IASCUFO’s communiqué from its recent Kuala Lumpur meeting (December 2024) reiterates this welcome of GSFA’s ‘voluntary intensification of fellowship within the Communion’—that is, GSFA’s covenantal commitments—‘as a potential source of renewal and fresh missional energy, the fruits of which may inspire others’. It concludes:

Despite our divisions, the Anglican Communion needs to find ways for the contribution of the GSFA to be more fully recognised and received within its wider life and mission.

These are significant and sincere expressions of welcome. Two senior GSFA primates (the Archbishops of Alexandria and South-East Asia) are signatories to the Nairobi-Cairo proposals, but IASCUFO has also committed itself to reaching out to GSFA’s leadership for further dialogue. These are all healthy and hopeful developments.

2. Decentre Canterbury

For the last century and a half, the Anglican Communion has been conceived as a family of autonomous churches which are all ‘in communion with the see of Canterbury’. This idea was popularized by Victorian ecclesiologists and took pride of place in the 1930 Lambeth Conference’s classic description of the Anglican Communion (Resolution 49). It is regularly rehearsed in the standard Anglican textbooks. For example, Paul Avis asserts in The Identity of Anglicanism: Essentials of Anglican Ecclesiology (2008):

The litmus-test of membership of the Anglican Communion is to be in communion with the See of Canterbury.

He goes so far as to call it ‘the ultimate criterion’. Furthermore, the constitution of the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC) defines membership of the Anglican Communion in similar terms, as ‘churches in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury’. (For fuller analysis, see Andrew Atherstone, ‘In Communion with the See of Canterbury?’, The Global Anglican, Spring 2024.)

Here, again, Anglican theories clash with Anglican realities. In its 2023 Ash Wednesday Statement, GSFA publicly rejected Justin Welby’s leadership of the Anglican Communion and declared that the Church of England, by its innovative liturgies for same-sex couples, has departed from the historic faith and broken communion with orthodox provinces. The possibility that Welby’s successor at Canterbury will reverse the Church of England’s trajectory is infinitesimally small. Several GSFA provinces have now begun the process of removing the phrase ‘in communion with the see of Canterbury’ from their constitutions. In a post-colonial world, there have long been strong reasons for decentring the role of England’s primate within the global Communion. But there are also now urgent theological reasons for this shift in the structures of the Communion.

The Nairobi-Cairo proposals recommend that ‘communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury’ in the ACC constitution is replaced by ‘historic connection with the see of Canterbury’. This is deliberately looser and open to wider interpretation, so that provinces no longer in full communion with Canterbury are still publicly validated as bona fide members of the Anglican Communion. It is a highly significant and long overdue change in Anglican self-understanding, from which other reforms of the old structures will naturally cascade.

Read it all at Psephizo