When a priest is ordained to the episcopate, he must make several promises before the ordaining bishops impose their hands on his head and call down the Holy Spirit. The principal consecrating bishop says to the man about to be consecrated: “The ancient rule of the holy Fathers decrees that the one to be ordained Bishop should be questioned in the presence of the people concerning his resolve to guard the faith and to discharge this office.” This means that the man about to become a bishop must bear public witness before all the faithful to his supernatural faith in the truth of the Gospel and his obedience of faith to all that has been revealed by God.

The ordaining bishop asks: “Do you resolve to proclaim the Gospel of Christ faithfully and unfailingly?” And if the bishop-elect answers “I do,” then the next question is “Do you resolve to guard the deposit of faith pure and entire according to the tradition preserved always and everywhere in the Church from the time of the Apostles?” And only if the priest affirms that he will guard the deposit of faith pure and entire can the rite of his ordination continue. But what is the deposit of faith?

In the New Testament Letter of Jude, the author writes to all who are called in Christ Jesus that because of false teachers and immoral behavior in the Church he “found it necessary to write appealing to you to contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude 1:3) And here we find the first meaning of the deposit of faith: the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints. That is what every bishop must promise to guard, and the refusal to be faithful to that sacred duty is among the worst possible failings in any bishop of any time and place.

The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation of the Second Vatican Council (Dei Verbum) puts it this way: “Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture form one sacred deposit of the Word of God, committed to the Church. Holding fast to this deposit, the entire holy people united with their shepherds remain always steadfast in the teaching of the Apostles, in the common life, in the breaking of bread and in prayers (see Acts 2:42), so that holding to, practicing, and professing the heritage of the faith, it becomes on the part of the bishops and the faithful a single common effort.” (DV, 10)

Dei Verbum then explains a crucial limit on the authority of bishops to teach: “This teaching office is not above the Word of God, but serves it, teaching only what has been handed on, listening to it devoutly, guarding it scrupulously and explaining it faithfully in accord with a divine commission, and with the help of the Holy Spirit, it (the teaching office) draws from this one deposit of faith everything which it presents for belief as divinely revealed.” (DV, 10)

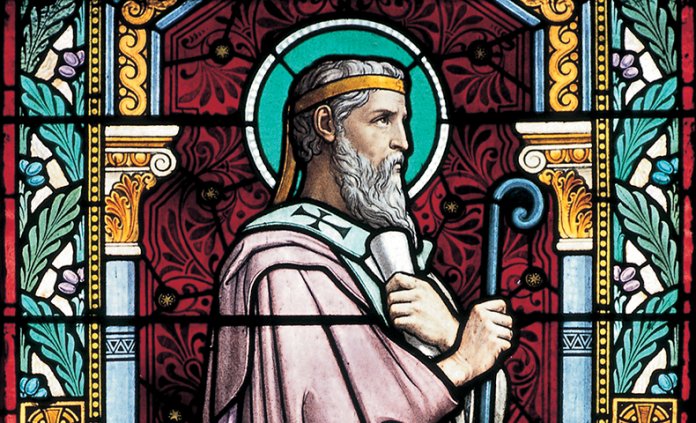

So the deposit of faith which every bishop promises to guard and transmit is both the content of the Gospel proclaimed by the Church and the limit of what may be taught as the revealed Word of God. And as a witness to this essential dimension of the Church’s life and mission, the Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes from Saint Irenaeus of Lyon in his treatise Against Heresies:

“For though languages differ throughout the world, the content of the Tradition is one and the same. The Churches established in Germany have no other faith or Tradition, nor do those of the Iberians, nor those of the Celts, nor those of the East, of Egypt, of Libya, nor those established at the center of the world … The Church’s message is true and solid, in which one and the same way of salvation appears throughout the whole world.” (CCC, 174)

Irenaeus was born in Smyrna (modern day Izmir, Turkey) and learned the Gospel from Saint Polycarp who learned the Gospel from Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist. For this reason alone, Irenaeus is important in Church history because he stands for the first generation of Christians to know neither the Lord Jesus nor any of the Apostles.

The transmission of the Gospel by the Apostolic Succession depends upon the rule of faith to which all who are ordained bishop must adhere with religious submission of intellect and will, and Irenaeus himself became a link in that chain. But Irenaeus is also important because of his extraordinary writings which defend and explain the Gospel, in part by refuting misunderstandings and false doctrine.

The main challenge to the Gospel in the time of Irenaeus, who served as the Bishop of Lyon in the late second century, was the strange stew of heresies called Gnosticism, and much of the surviving written work of Irenaeus is a refutation of the doctrines promoted by Gnostic heretics, not a few of whom claimed to be Christians and held offices in the Church. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!

In our time there are new challenges to the deposit to faith, and not a few of those failing to guard that deposit pure and entire are bishops in the Church. The willingness of Catholics to abandon that which has been preserved always and everywhere in the Church from the time of the Apostles has been on full display in Germany during the long debates of their Synodal Way, and that same willingness to surrender to the Neo-Gnostic fantasies of the Sexual Revolution has been a regular feature of life in professional theological guilds for decades.

And now comes a document from the Holy See on the possibility of priests conferring private, non-sacramental, non-liturgical blessings on those whose public sexual relationships do not correspond to the Gospel.

Read it all in A New Catholic Reformation