In his 2009 book, The Marriage-Go-Round, Andrew Cherlin argues that America has a distinct family culture marked by frequent marriage, divorce, and brief cohabitation that either dissolves or transitions into marriage. Cherlin argues this is a distinct pattern compared to other western nations. Evidence suggests U.S. marriage culture is distinct from trends in Canada.

Despite the proximity of the U.S. to Canada, and the sheer volume of American pop culture that flows northward in exchange for a handful of Canadian-born comedians, marriage and family culture in Canada retains some distinction from its southern neighbor. These distinctions emerge when examining the living arrangements of Canadian children. But one doesn’t need to leave Canada to find significant regional differences. For example, family structure in Quebec, Canada’s second most populous province, continues to reflect a distinct social culture that is unique in North America.

At the Canadian-based think tank Cardus, we recently analyzed custom tabulations from the 2021 Canadian Census on the family structure of children aged zero to 14 in private households. These tabulations include the parental marital status of children living in intact families and stepfamilies. We examined the portion of intact families and the marital status of children’s parents as an indirect measure of family stability.

Nearly one in five Canadian children witness the separation or dissolution of their parents’ relationship by age 18. Despite this high percentage, little public attention is given to family structure and child well-being as a result of family breakdown. The public discourse around poverty or economic inequality in Canada rarely acknowledges the empirical evidence pointing to the correlations between family structure transitions and poorer outcomes for children, including lower academic achievement and behavioral issues.

Statistics Canada first delineated between intact families and stepfamilies in the 2011 Census. This is a valuable addition to the national statistical agency’s reporting. Unfortunately, this recent emphasis has resulted in less reporting on the legal marital status of two-parent families. While Statistics Canada collects data on the marital status of children’s parents, the married/cohabiting distinction is not as readily available. The custom tabulations we examined account for this distinction.

Good News for Family Stability

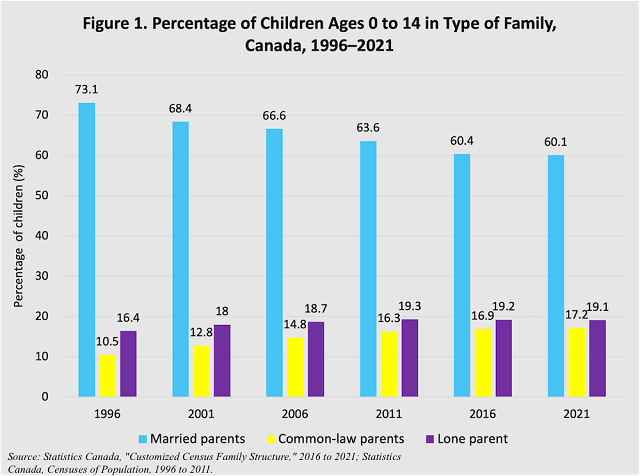

In a bit of good news for family stability, the decades-long decline in the portion of children living with married parents has remained relatively stable since 2016 compared to the previous census intervals. About 60% of children in Canada live with married parents, and about 19% with a lone parent. Approximately 17% of children live with common-law (or cohabiting) parents.1

Stepfamilies

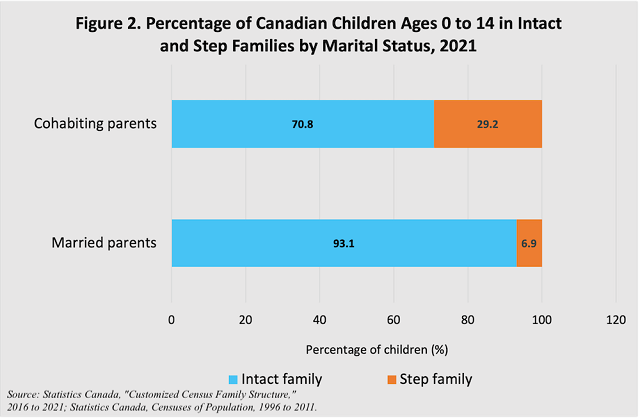

The data on the marital status of stepfamilies shows some distinct differences between Canadians and Americans. The portion of children living in stepfamilies in both countries is around 9%, but Canadian children living in stepfamilies are more likely to live with cohabiting (common-law) parents than married parents. About 55% of children in stepfamilies live with a biological parent and their common-law partner as compared to 45% of children living in a married stepfamily. This is a mirror reversal of the United States, where 55% of children in stepfamilies live with a biological parent who is married to a partner.

In Canada, the portion of children living with married parents is about three times more than the portion of children living in cohabiting homes. Yet children living in stepfamilies are more likely to live with cohabiting adults. Another way to view the data is to examine the portion of children living with common-law parents and married parents that are stepfamilies. Nearly 30% of children living with common-law parents are in stepfamilies, compared to 7% of children in married families.

This speaks to the idea that the rapid “marriage-go-round” Cherlin identified in the U.S. has likely not yet made its way north. Divorced Americans are more likely to enter a subsequent marriage compared to previously married Canadians. About 20% of Canadians who married in 2020 had been previously married. This compares to about 40% of Americans who married in 2015. Census data is of course a snapshot of a point in time, but we speculate that divorced Canadian parents who re-partner are more likely to cohabit or perhaps cohabit for longer periods compared to their American peers.

Quebec’s Distinct Family Culture

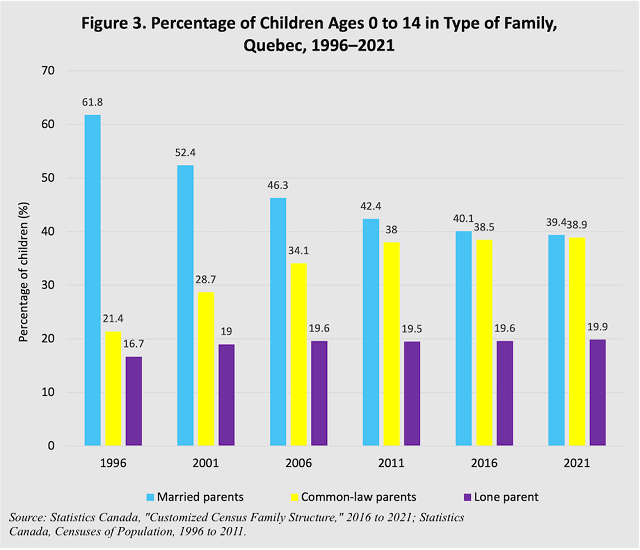

There are distinct regional differences among Canadians when it comes to family formation. The steep decline of marriage in the province of Quebec has resulted in nearly as many children in the province living in cohabiting families (38.9%), as married parent families (39.4%). This has a non-trivial impact on national family structure statistics. For example, when excluding the Quebec data, the portion of children in the rest of Canada living with common-law (cohabiting) parents decreases from 17.2% to 10.7 percent.

A slightly larger portion of children in Quebec live in stepfamilies (12%) compared to the national average (9.2%). With the prevalence of cohabiting relationships in Quebec, a much larger portion of children in stepfamilies live with cohabiting parents (72.6%) compared to the national average (55%).

As Quebec has a distinct history and culture within Canada, it’s difficult to interpret what insights the province holds for the rest of Canada. Our read of the evidence suggests that cohabiting relationships within Quebec are more stable than in the rest of the country, but less stable than marriage both within the province and within the rest of Canada. At the same time, it appears marriage within Quebec has become more prone to dissolution compared to marriages outside of the province.2 Finally, data from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth shows that among children under age 18 in Quebec, 23% have experienced their parents’ divorce or separation. This is second only to the east coast province of New Brunswick as the highest percentage among all provinces and higher than the national average of 18 percent.

What’s Missing in Canadian Discourse

Americans remain more marriage minded than Canadians, and this is reflected in the public discourse around family structure, poverty, and inequality. The American conversation more readily acknowledges the role of family structure, even as there is strong disagreement about public policy approaches to marriage and two-parent families. That Canada only recently began collecting national divorce and marriage rate data after a 10-year break reflects the lack of consideration of family structure in policymaking. Whatever the reasons for downplaying family structure in Canada, our public discourse is weaker for it.