The perennial Anglican identity crisis is taking on a new urgency. As numbers of converts to Roman Catholicism, Orthodoxy and Pentecostalism grow, harried voices try desperately to justify our distinctive charism. Since the announcement of a female Archbishop with opinions on sexuality and abortion which diverge from those historically normative of the Christian faith, an estimated 80% of Anglicans worldwide have reaffirmed their breach with Canterbury. The majority of Anglicans abroad are no longer defined as such by connection to the primatial see. The same now effectively applies to a growing minority within the Church of England itself. The majority of Anglicans worldwide are all the keener to define the Anglican genius as something other than liberal Protestantism with professed episcopal order and old colonial links.

This gives the backdrop to the latest iteration of the quest for “Anglican distinctives.” Some of the boldest claims come from the United States, as the Anglican Church of North America finds that the opposition to Episcopal Church teaching on sexual morality which precipitated its founding is not enough to constitute a lasting identity, and itself begins to show new cracks. Even on the more conservative side, instead of unity, we find two camps, Reformed and Catholic, each striving for doctrinal clarity, and trying to stake their exclusive fidelity to historical Anglican doctrine.

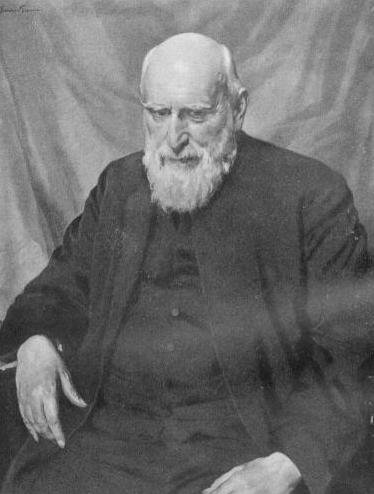

Today I want to explore how Darwell Stone, Principal of Pusey House from 1909 to 1934, would view this situation. Writing a century ago, he would have seen the quest for Anglican distinctiveness as futile: firstly, because Anglican “distinctives” are necessarily provisional, and ultimately undesirable; and secondly, because since the Reformation, the English Church has harboured advocates of two rival and incompatible approaches to ecclesiology.

Stone offers us an approach which looks beyond the limits of post-Reformation formularies to seek Catholic truth in Scripture and the consensus of antiquity, making apostolicity the test of true doctrine, rather than appealing to later periods of historical theology as constitutive of some authentic “identity.” In practice, this often means looking East. His method, I suggest, may yet spare many fools our errands.

I. Against “Anglican Distinctives”

“Truth is Catholic, but the search for it is Protestant,” said Auden: an aphorism apposite to the Tractarians of the 19th century, convinced that they could reconcile Catholic truth with the Church of England’s Protestant formularies and divines. Stone was unconvinced. Tractarian reliance on post-Reformation sources was at best a happy fault. While their conviction did indeed help turn the Church back towards those essentials of Catholic faith which she had retained, Stone found it wanting in light of historical scrutiny.

Stone acknowledged a great debt to Keble and to Dr Pusey, but he was of a different generation. Anything that was distinctly Anglican, Stone saw as a lamentable deviation from the pristine Catholic truth. The ingenious discovery of readings “patent of Catholic interpretation” helped to establish that Catholic belief had been “contemplated, tenable and lawful” in the post-Reformation Church; but convinced Protestants could make similar claims from the very same formularies. “I do not think,” he comments in a 1904 paper on Anglo-Catholic Tradition, “a claim which represented [Tractarian theology] as the only lawful English doctrine could be justified by history.”

The formularies were, in short, permissive of rival and incompatible interpretations. Stone thought this a matter of design rather than accident—that they were compiled to accommodate irreconcilable opinions. So, those Tractarians and Evangelicals alike who make exclusive claims for historically authentic Anglicanism do not, in Stone’s words, “sufficiently realise that the official policy of the Church of England in the 16th and 17th centuries had been rather to include than to exclude.” The Church of England deliberately maintained “the policy of leaving as open questions very many matters on which there was no conciliar decision of the Universal Church requiring acceptance… of condemning certain extreme positions, and allowing as lawful widely differing opinions which came between them.”

The role of the theologian, then, is not to argue on the grounds of historical doctrine for the exclusive claims of either Catholic or Protestant theology on the Church of England. Rather, it is to appeal to truth as the sole criterion, and to seek that truth far beyond the narrow limits, temporally of the last four hundred years, and spatially of these islands. Anything falling within those bounds, that is, anything distinctively “Anglican” should be subjected to the most rigorous scrutiny; because such distinctives, he writes in The Church, its Ministry and Authority, “can only await the judgement of the whole Church, if in the Providence of God the reunion of christendom should be brought to pass.”

Was Stone suggesting that Anglicanism should not exist? In a sense, yes: but he applies the same caveat to both the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox churches. Insofar as any of us teach anything distinctive, those distinctions too await the judgment of the whole Church. Now this rests on the presupposition that neither Rome nor the East exclusively constitutes the entire Church. One might say that if Anglicanism has any justifiable “distinctive,” it is the recognition that all distinctives are provisional; or, the distinction of aspiring to be without distinction.

II. Antiquity and consensus

So if Anglican distinctives are futile, what should guide us instead?

Stone’s acknowledgement of the provisionality of our distinctions does not mean that Anglicans should stick their heels in the mud of Reformation formularies and await their judgment on the happy day of visible Church reunion. Nor does it mean retreating into latitudinarian quietude. Stone is quite clear on how we should assess the truth of those distinctives and duly abandon them.

Stone’s dogmatic basis is divine revelation. Criticising Lux Mundi, he wrote to the Guardian in January 1890: “there is a line between what is known from nature, reason, and experience, and what is known from revelation, since the latter is the direct gift of God, and conveys absolute truth.” The older Evangelicals and Tractarians agreed on this. It was their modern Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical successors who erred.

In c. 14 of his treatise on Holy Baptism, Stone sets out his commitment to the universality of the sensus fidelium. Revelation is contained in Holy Scripture; the words of Our Lord are divine and infallible; the apostles and other New Testament writers carry the authority of those commissioned and inspired by God; and the Universal Church, as Christ’s mystical body indwelt by the Holy Ghost, is the divinely appointed instrument for teaching Christian truth. Where any “distinctives” do not enjoy Scriptural warrant and universal consensus, they may be offered as permissible beliefs, but it exceeds the authority of any part of the Church to anathematize those who do not hold them.

Following this rule, Stone sought to make the Church of England as theologically undistinctive as possible. To that end, his appeal to consensus is unified with the appeal to antiquity. His biographer Cross claims that Stone “made no claim to originality. Indeed, he at all times would have regarded this quality in a dogmatic theologian as something to be shunned.” This is because the revelation of Christ in Scripture and the Church is unchanging. “We do not mean,” Stone wrote in the Church Quarterly Review of April 1890, “that the definition of a later age existed from the first or that questions afterwards prominent were even thought of in the earliest times. Growth, explanation, inference there certainly were. But the faith about Christ… was not left to be puzzled out in a maze of conflicting thoughts; it was a revealed truth, committed as a trust to the Catholic Church.”

Hence Stone’s method is typically the catena: on any given topic, he begins with Scripture, and moves onto Patristic then mediaeval witness, citing creeds and canons, before moving onto any points of contention among Reformation divines, in strict chronological order. He quotes extensively and with nowadays rare disinterest, taking into account rival positions to his own. In every case, he seeks the truth in the path of least distinction.

Antiquity and ubiquitous consent—quod semper, et ubique et ab omnibus—are for Stone the hallmarks of Catholic truth.

III. Looking East

Where do we find those hallmarks? Stone’s answer, often, is to look Eastward.

Nothing in Stone’s writing suggests an infatuation with the East. He is not a Charles Grafton, for example, to pine especially for reunion with the Orthodox. His appeal to the East is admiring, but intellectual—not as a means of validating “Anglicanism,” but rather as an independent witness to intra-Western doctrinal debates popularly framed as “Calvinist versus Romanist.” Whilst not uncritical of the Eastern claim to complete changelessness over the centuries, it was a claim to which he aspired, and which he thought better than Newman’s arguments for development of doctrine.

Stone’s Eastern sympathy becomes concrete in specific doctrinal debates, especially over the sacrament of Confirmation. The Church of England has retained the threefold sacraments of initiation common to the entire Catholic Church. However, the Church of England follows the Roman innovation of separating Confirmation and Holy Communion from infant Baptism—an error, in Stone’s view, that deviates from the practice of the undivided Church. He wrote in private correspondence in 1918, “the East enjoys a greater appeal to unbroken antiquity than Rome, especially given Rome’s sundering of baptism from confirmation and communion, [which is] retained by the English church.” The East, Stone shows by sundry examples from the fathers and the ancient liturgies, is right to chrismate and communicate even infants immediately on baptism. This Western distinctive is a deviation from the universality and ubiquity of old, of which the East is a more reliable marker.

Not that Stone was unsympathetic to Roman Catholicism. In opposition to many Anglican bishops of his day, he thought that Rome was mostly right rather than mostly wrong. His summary of Tractarian sympathies in the introduction to The Faith of an English Catholic reflects his own: “a desire to find out all that was good in Roman and Eastern theology and life, to search for agreement rather than for difference, to adapt and use the principles and methods of Roman and Eastern thought and devotion.”

Stone was not interested in defending Anglican, Roman Catholic or Eastern doctrine per se. He sought only the ancient consensus of the Catholic Church. Nonetheless, he wrote in a letter of 1928 to a religious sister troubled in conscience about the state of the English Church, “for the maintenance of the past, and the application to the present I do not think that it can rightly be said the church of Rome has been more successful than the Orthodox Church of the East.” The East was where the ancient consensus was best preserved.

He had clearly thought about becoming a Roman Catholic, but wrote to a correspondent considering the same course, “I should find the greatest difficulty in excluding from the church, not only The Church of England, but also the whole eastern Orthodox Church. And the study of history makes it clear to me that the claims of Rome are not well founded.” Those claims include universal papal jurisdiction and papal infallibility, but above all, it was the anathematization of Christians for not holding beliefs which have demonstrably not commanded the universal assent of the Church—that is, “distinctive” doctrines–that Stone found Rome wanting.

As for becoming Orthodox, Stone seems to have considered that, too. I can find only one reason why he would not do so. In 1918 correspondence with Rev. P.H. Leary, Stone wrote: “I am not myself thrown back on the Eastern Church because of the, to me, seeming impossibility of their position in excluding all the West from the church.” In other words, it is again that anathematising tendency that Stone abhors. So, he concludes with a resignation that some people here may find sympathetic: “So I stick on in the Church of England remembering that, if the Reformation, as well as other influences, made a mess in a great many matters, there is plenty of mess also in Rome and the East.”

Whatever that Eastern mess might be emerges far less clearly in his writings than the mess he alleges in Rome. As I say, I can find only one instance. But Stone believed the English mess, for all its muddle, at least did not claim to be anything other than provisional—and that this humble truthfulness was itself a Catholic virtue. Freedom from the dogmatic anathematization of half of Christendom was something Stone valued enough to remain in his mother Church, for all its mess.

IV. Sacramental Ecclesiology

Let’s turn to the messy detail, namely, ecclesiology: or rather, the mess of the two rival and incompatible ecclesiologies which vied for the assent of the Church of England, namely the Catholic and the Reformed.

What the Tractarians rediscovered, Stone wrote in 1904, “was a fresh sense of the momentous fact that God had become man. With it came a conviction of the complete change thereby affected in the relations of man to God and of God to man.” Starting with Keble, the Tractarians understood that the Church was a visible body demanding visible union, by which spiritual union with Christ is effected. This understanding was based on what Stone calls the “vital” sacramental principle, whereby outward signs effect an inward spiritual grace, a principle grounded in the God-man Christ Himself.

“Union with God,” Stone begins his volume The Holy Communion, “is the highest aim of human life.” He furnishes the reader with examples of this orientation to God drawn from the widest extent of human history and cultures. But it is uniquely in the Incarnation of Our Lord, “truly God and perfectly man,” that these vague longings are duly harnessed. Scripture and the tradition of the earliest Church reveal the Sacraments as the means whereby this longing is satisfied, as the means whereby Christians are unified with Christ, “and through Him with the Father and the Holy Trinity.” “The Incarnation, Atonement, Baptism and the Eucharist,” he writes, “are God’s answer to man’s pleading for Communion with Him.”

The Tractarian recovery of the sacramental principle followed from their emphasis on the Incarnation. For, “in the ancient Church, the use of the word [sacrament] was so wide that the Incarnation itself was described as a sacrament;” that is, as a symbol, “with that rich meaning in which the word symbol was used in the ancient Church, and not in the bare and narrow sense given to the word by many Protestant divines.”

The sacraments objectively “effect that which they signify,” as objectively as the fact of the Incarnation. The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, irrespective of the faith of the recipient, is as undisputed in the Fathers as the real regenerative grace imparted in Baptism. Only heretics anciently rejected either claim, typically concomitant with Christological error: gnostic dualism of one kind or another driving a wedge between the spiritual and material.

The Church as visible and sacramental Body of Christ is not merely incidental to God’s response to the human desire for Communion with Him. Scripture and the earliest patristic witness show that the Apostles were bequeathed a specific mode of organisation to this end. As Stone puts it in the Outlines of Christian Dogma: “Since the day of Pentecost… the closest means of union with the glorified humanity of Christ… are in the mystical body of Christ, that is, the Church, and are open to man in the use of the Sacraments.”

Citing the parables of the wheat and tares and the dragnet, Stone argues that the Church is a sacrament of the Kingdom, which contains all the baptised, whether good or bad. There cannot therefore be a distinction between the visible and invisible Church in this world, whereby only the elect are invisibly true Christians, leaving those visibly baptised unsure of their predestination to damnation or election. The Church, visibly one, comprises all who are unified with Christ through the visible sacraments of initiation: Baptism, Confirmation and the Eucharist.

Despite the Western error of temporally separating the administration of these sacraments, and, Stone writes, “in spite of strong pressure from determined opponents of the truth, the Church in England, both in the sixteenth and in the seventeenth century, was careful to maintain the doctrine of Baptism which, as enshrined in Scripture and taught by the Universal Church, may rightly be called Catholic” (On Holy Baptism 58). This is borne out by the formularies, including the Thirty-Nine Articles.

A Reformed ecclesiology which sunders the visible Church from the invisible demands the rejection of baptismal regeneration and of the objectivity of both the dominical sacraments. It neither conforms to the teaching of the universal church, nor has ever been maintained by the Church of England. The error Stone identified in such an ecclesiology was less in what it said than in what it omitted: it admits of divine revelation but omits the sacramental body necessary to perpetuate and to consummate the truth that this revelation teaches. “The Church,” Stone wrote in 1904, was anciently understood “not only as the home of revealed truth but also as the storehouse of divine grace… as the church was the keeper and teacher of the one, so it was the custodian and bestower of the other.”

The Church of England’s ecclesiological foundation was firmly, even providentially, retained, despite the efforts of the Puritans. But on top of that firm soil, the Church of England’s formularies deliberately grant a rather shaky latitude between Calvinist and Catholic interpretations of how Christ is present in the Eucharist. It is not that there are no boundaries to permissible belief: Zwinglianism is prohibited. Stone thinks that the latitude which remains is too broad. Catholic ecclesiology is dependent on an objective theology of the Sacraments, which in turn rests on sound Christology. So he would have us tighten the bounds, and reject the Calvinist “distinctive” — not by appealing to Reformation formularies, but to antiquity and ubiquity. Once we are past receptionism, though, and into sacramental objectivism, the precise definition of how Christ is objectively present in the Eucharist is a matter which enjoys no patristic consensus. So, after a balanced treatment of views on Transubstantiation – which Stone, in point of fact, favoured over Puseyite consubstantialism – he concludes: “In the mystery of the Eucharist, where human thought is so apt to go astray, and human language is so inadequate to express even human thought, the interpreter will be most likely to be right who is patient of a wide latitude of interpretation and gentle towards what seemed to him offending expressions.”

Where Stone sees error, it is in exaggeration of one tenet at the expense of another, and in uncharitableness of application. His theology seeks fullness, Catholicity proper; it is deficiency and lack that makes theology lopsided. Like the Evangelicals, Stone accepted the authority of Scripture; what he could not accept was that Scripture alone was sufficient. Like them, he could accept that the Church was a body of the faithful and teacher of revealed truth; but he could not deny that she was also the custodian of the Sacraments by which that truth can be effected.

Stone calls clearly for full, visible reunion of the Catholic Church. The outward and visible sign of the Church must correspond to its invisible unity. But this, he avers, cannot mean submitting to one part of the Church which claims that its readily falsifiable particulars are in fact universals, and enjoy an antique consensus when they clearly do not. Worse still, to acquiesce in the anathematisation of Christians for holding positions which have been held by saints of the Church. The Church of England has erred in taking unilateral actions which move against the criteria of universality and antiquity, since these are the means towards the visible unity demanded of the Church. For that union, we will need to identify and to discard our “distinctives.” But, Stone says, we are not the only ones.

In Stone’s words, ”nothing ought to be denied to Rome by England or the East which Rome can rightly claim in the light of Scripture and history and dogma, and nothing ought to be granted to Rome of which Scripture and history and dogma demand rejection. Sacrifices on all sides will be needed if the great work is to be accomplished; but they must be sacrifices in which no Catholic principle is on any side abandoned.”

V. Stone for today

This brings us to today’s Anglican identity crisis. Stone is surely right that two rival ecclesiologies—one grounded in sacramental objectivity, and the other in the subjective and imperceptible criterion of individual faith—cannot coexist. We see the fallout of that in the Church of England and the wider Anglican communion today.

When Stone was writing, there was far greater doctrinal harmony on essentials among Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant churches, especially on today’s divisive matters of sex: digressions from common practice in that regard began with contraception, which until the 1920s was as much prohibited to Anglicans as to Roman Catholics or the Orthodox. By then, the Tractarian movement had achieved considerable practical success in restoring the Church’s latent Catholicity in sacramental doctrine and ecclesiology—even if, as Stone recognized, their historical arguments for this were flawed. The outward signs of this recovery in ritual and vesture were commonplace. The Church of England then could make a strong claim still to the twofold Tractarian criteria of the ubiquity and antiquity of her faith. With the great post-war growth of Anglo-Catholicism, by 1926, Stone was hopeful for reunion, “whether with Rome or with the East,” as a “step towards a union which may include all Catholics of the West and Orthodox of the East, and finally gather into itself all Christian societies.”

But that was in the 1920s. Since then, beginning with the 1930 Lambeth Conference’s approval of contraception, a series of unilateral innovations has emerged from the progressive elements of all three major church parties. These have hindered the prospect of even internal union among Anglicans, let alone reunion with the wider Catholic Church. The result is a power struggle, with Evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics talking their confected doctrinal histories past each other, while progressive forces with their hands on the levers continue to move the church away from Stone’s criteria of universality and antiquity.

Stone offers a way through this impasse. Like Mascall, Lewis, or Rowan Williams after him (and we might add Hans Boersma to that list), Stone emerges as a theologian of “mere Catholicity.” Our challenge is not to prove that we are more “authentically Anglican” than Canterbury—it is to show what this mere Catholicism means in practice.

Any Anglo-Catholic future is going to depend upon generosity and good faith engagement with Evangelicals. That mutual generosity must be grounded, as Stone insists, in the priority of Scripture as the basis of a fully Catholic ecclesiology—one which neither reduces the Church to an association of Bible-believing individuals, nor empties Scripture of its divine authority through critical methods which subordinate revelation to reason. Stonelike firmness on divine revelation and his willingness to abandon distinctives may prove a fruitful point of contact between Evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics to this end.

So what does this mean for us, here, today? Pusey House’s vocation is to seek and proclaim Catholic truth. It means we must deepen our sacramental theology and practice, recovering not merely the Bible but the Bible as interpreted by the universal Church. It means looking to the East for an independent witness to Catholic truth. It means building bridges with Orthodox and Roman Catholics who share the same commitment to Scripture and universal consensus, even where disagreements remain. And amid those disagreements, it means being committed to the truth over the defence of doctrinal distinctiveness, marking Stone’s sentiment: ”Want of generosity will usually mean failure to understand.”

In an age when the majority of Anglicans have broken communion with Canterbury, may this House continue as the undistinctively Catholic home for all who share Stone’s vision: the full and visible reunion of the Church.