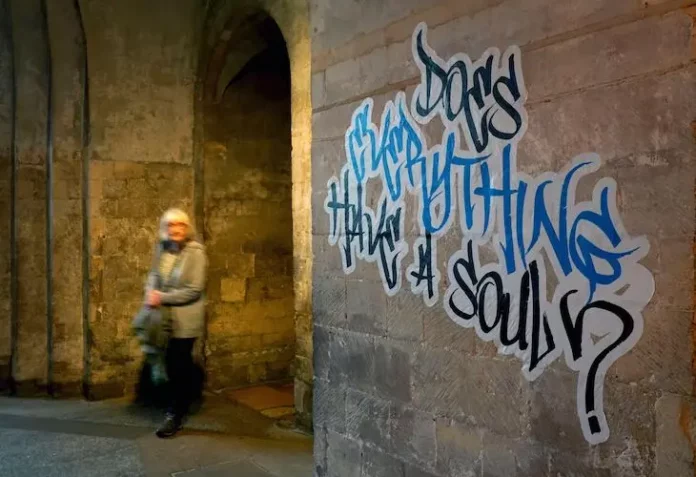

The first, and the lasting, impression one gets from Canterbury Cathedral’s new graffiti-style art instillation is just how reasonable and normal are the questions it quite literally poses. That’s some feat for an exhibition that purports to be ‘thought-provoking’ and ‘dynamic’ while simultaneously attracting such derision – even provoking the ire of the US vice president, J.D. Vance. Echoing the feelings of many people in this country, he asked why the cathedral’s curators had to make a ‘beautiful historical building really ugly’.

What really gets people riled about this exhibition is not so much the questions it raises, but its motives and its methods

Yet there’s nothing shocking in the concerns expressed in the brightly coloured tags affixed to the walls throughout the building (they’re actually stickers). Representing real questions made by members of a workshop assembled by the exhibition’s creators, regarding the one thing they would like to ask God, their queries are frequent and commonplace: ‘Are you there?’, ‘Is this all there is?’, ‘Why all the pain and suffering?’, or just ‘Why?’. Such questions may indeed strike some as hackneyed and trite, the kind of things infants ask their parents and elders. But they are the ones that race through all our minds in times of disaster, emotional crisis and bereavement.

Other callow petitions on display here are less forgivable, seeing that the Christian church already has at its disposal correct doctrinal replies. ‘Are you there?’ (answer: yes). ‘Will there be a next time?’ (again: yes). ‘Is illness a sin?’ (of course not). ‘Does everything have a soul’ (absolutely not). The eternal, and some would say, insoluble, problem of evil gets a prominent showing, and warrants more lengthy answers. ‘Why is there so much pain and destruction?’ repeats one daub. The explanation for this, according to Christianity, is that God endowed humans with free will, and evil exists because He allowed us to make bad decisions. Adam was the first man and the first man to do wrong. That’s why he was punished.

There’s no harm in asking ourselves and others these questions, even if some will never be satisfied with answers that only beg further questions: then why did an omnipotent God make humans susceptible to moral error in the first place? And rationalist atheists will never accept the hypothesis of an all-powerful, all-loving God. Logically, in light of the suffering in the world, He can’t be both.

What really gets people riled about this exhibition is not so much the questions it raises, but its motives and its methods. It encapsulates the incessant and desperate desire by the Church of England to appear relevant, by no matter how vulgar, disrespectful or cringeworthy means necessary. It was not enough for this exhibition to broach the problem of evil through the medium of ersatz urban scrawls – and in a decidedly dated style of clean, luminous graffiti last seen on the front cover of hip hop albums in the late-1980s – it had to do so via sub-par hip hop lyrics.

‘If you made us all in your form. Why the violence the killing the storm’, reads another graffito. And bad poetry: ‘This is my question for a god up above. Why so much violence instead of love.’ And soppy, saccharine sentiment: ‘Why did you create hate when love is by far the more powerful.’

Canterbury Cathedral, the principal church of the worldwide Anglican Communion, has form in this department. In February last year it hosted four two-and-a-half-hour dance parties in its hallowed space, the ‘rave in the nave’, an event that was likewise greeted with exasperation. The carry-on at Canterbury has left many conservatives in a state of despair. Reacting to this exhibition’s unveiling, the Rev Marcus Walker, rector of St Bartholomew the Great in London and chairman of the campaign group Save the Parish, told the Daily Telegraph that he would like to challenge the cathedral ‘not to embarrass the rest of the Church of England for one clear calendar year.’

Yet many suspect that the cathedral isn’t out of step with the Anglican establishment. Read it all in The Spectator