“…the question in not can some women be excellent professors? The question is: is it possible to have an academia that is majority female and is still as committed to, and still respects, the unhindered pursuit of unpopular truths as much as the old predominantly male academia did?” Helen Andrews

This is something that I have been musing on for quite a long time – I have wanted to work up a ‘steel man’ argument against women bishops as I have found most of the standard argumentation (on both sides) lacking in vitality and effect. I am in favour of the ordination of women but I have been increasingly disquieted about what has been happening in the Church of England as a whole, and the elevation of Sarah Mullally to the Archbishopric of Canterbury has brought matters to a krisis.

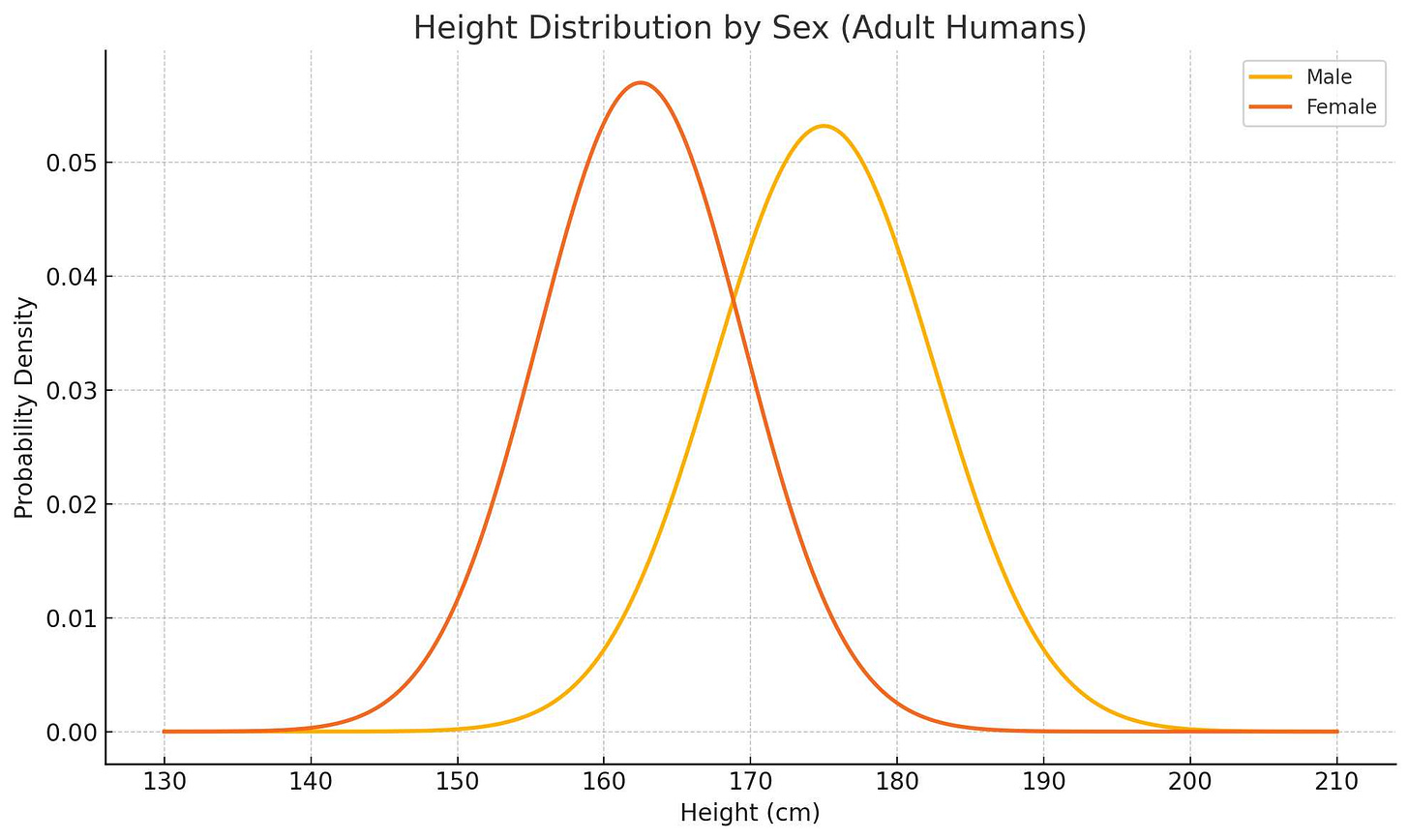

Let’s begin with another bell curve:

This one shows the normal height distribution of men and women, and is not controversial. Some of the implications, however, can be. Some women are tall; you’ll even find some women who are taller than the majority of men (my lady Brienne of Tarth!) but if you want to build a team of tall people then that team will be mostly men, and if you want a team of really tall people then it is reasonable to expect it to be exclusively men. If the purpose of an organisation requires the selection of really tall people for a competition, and if some parties in that competition select entirely for height, whereas some also impose a gender quota of 50% female, then those latter parties will have a shorter team than the others – and in the competition those latter parties will lose.

The question, therefore is: is there something essential about being a bishop that is distributed unequally between men and women?

That there are differences between men and women, differences that include psychological disposition, is an ancient wisdom rejected in Modernity but now becoming widely accepted once more. Here are some examples: physical aggression is much more common amongst males, and this applies cross-culturally (Archer 2004); non-physical aggression, including gossip and social exclusion, is more common amongst females (Crick and Grotpeter, 1995). Social conformity – not surprisingly given those statistics on aggression – is higher in females, especially in face-to-face settings (Eagly & Carli, 1981), and most especially when group pressure is visible (ie in a public group, Bond & Smith 1996). Most fundamentally the male brain tends towards an object-orientation whilst the female brain tends towards a person-orientation (Su et al., 2009), preferences which manifest early in life (Alexander et al., 2009) and which are reflected in things like choices of career (more male engineers and surgeons, more women primary school teachers and paediatricians). The more egalitarian a country (eg Scandinavia) the more pronounced the difference (Schmitt et al., 2008).

So, in terms of normal distribution, it is fair to assert that for certain qualities, such as social conformity, the bell curves for women and men are different, and that the norm for women is more towards social conformity than the norm for men.

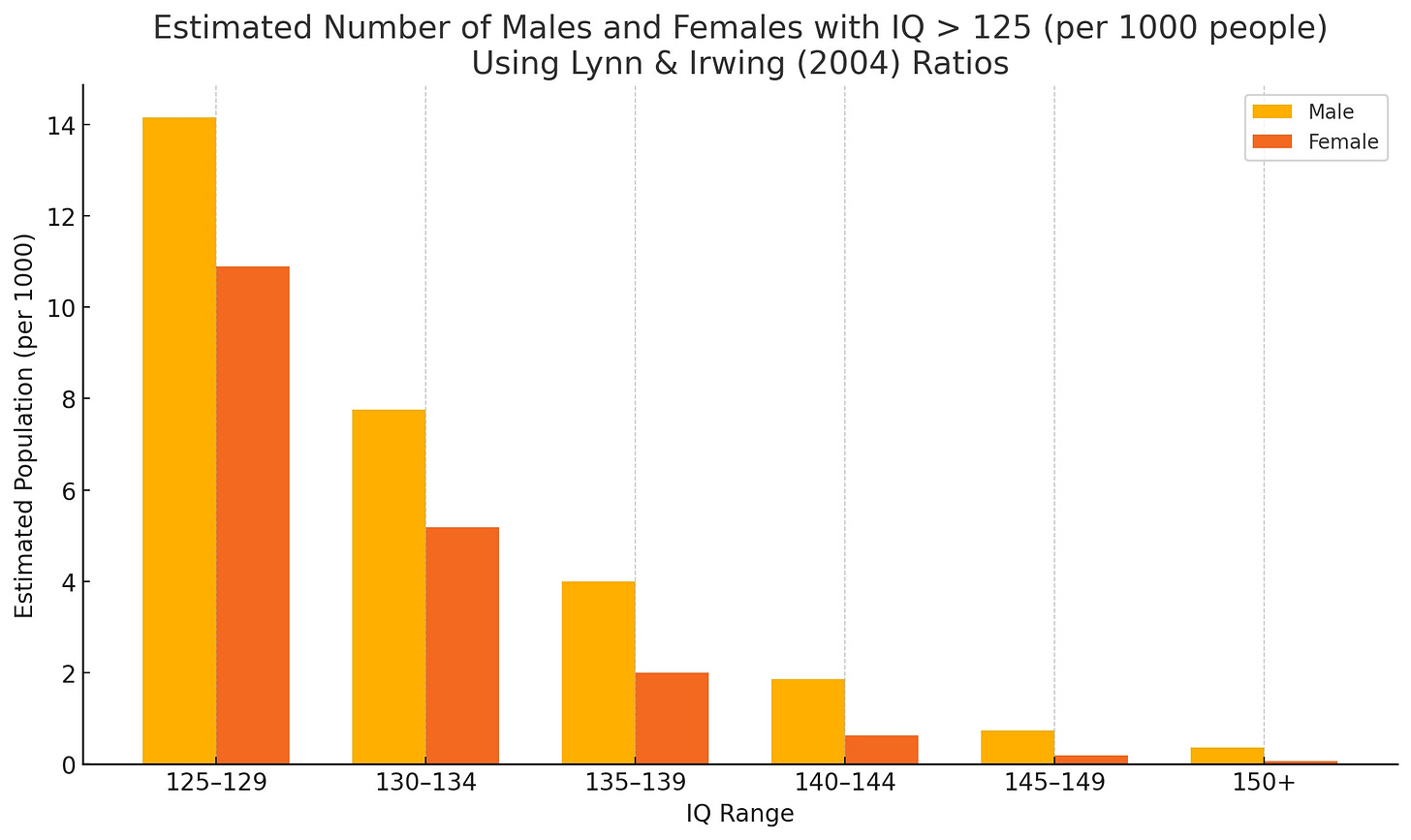

As well as differing psychological dispositions on average we also need to account for greater male variability in certain qualities. What that greater variability means is that the representation of males is higher than females at the extremes of the bell curve for certain qualities (a ‘fat tail’). As the saying has it, there are many fewer female Mozarts for the same reason that there are many fewer female Jack the Rippers. Are there any qualities that might be relevant for being a Bishop that have a ‘fat tail’ like this? Yes – intelligence.

This is what the distribution of high intelligence looks like, for a model population of 1000 people, between male and female (UK historic norm for IQ):

What the evidence shows is that in areas that place a premium upon adherence to truth (over against social conformity) and intellectual ability, such as in academia, a preponderance of men is inevitable – for so long as those qualities are selected for. Where those qualities are not selected for then those qualities will recede in prevalence and other norms will come to dominate. This is the gist of Helen Andrews’ argument about the corruption of academia by ‘wokeness’, which she sees as the inevitable consequence of the establishment of female norms – ‘feminisation’ – see the video linked above.

So has this happened in the Church of England as well? Is there something essential about being a Bishop, in particular, that was historically selected for but is no longer chosen? I believe that there is, and it centres upon the ability to teach the faith.

Read it all in the Elizaphanian