Daniel Pipes spoke at the David Horowitz Freedom Center’s 2021 Restoration Weekend, held Nov. 11th-14th at the Breakers Resort in Palm Beach, Florida. He addressed the significant new phenomenon of a swelling number of ex-Muslims. An edited transcript follows.

I shall focus here on the phenomenon of ex-Muslims in the West, leaving aside the Muslim-majority countries. The numbers are imprecise: one estimate has about 15,000 Muslims who de-convert or leave Islam every year in France and 100,000 who de-convert in the United States. Over time, this amounts to a significant population; perhaps one-quarter of people of Muslim origins living in the West are now ex-Muslims. They roughly counterbalance the converts to Islam, who tend to be better known, figures like Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and Keith Ellison. That said, some ex-Muslims are also very well known, if much more discreet; hello, Barack Hussein Obama.

In the United States, a poll found that about 55 percent of ex-Muslims become atheists, about 25 percent Christians, and the other 10 percent are not known. Ex-Muslims have an impact in three distinct ways: by publicly leaving Islam, by organizing with other ex-Muslims, and by rejecting the Islamic message. Let’s look at each of these activities.

First, publicly leaving Islam in of itself constitutes a major statement. Though generally forbidden in Muslim-majority countries, doing so is of course legal in the West. But even in Europe and North America, an ex-Muslim faces rejection by the family, social ostracism, humiliation, curses, threats, reprisals, and sometimes even violent attacks. So, it always requires courage and stamina.

Accordingly, de-converting from Islam tends to be cautious or hidden. Salman Rushdie clearly left Islam but pretends to remain a Muslim. The same holds for the pop star Zane Malik, the former president of Argentina Carlos Menem, and, as mentioned, Barack Obama. Born and raised a Muslim, Obama quietly left the faith and then inconsistently denied doing so, something the media happily abetted.

Other de-converts go public and, knowing Islam intimately from within, spread this awareness. They include Ibn Warraq, the author who has written some twelve books about Islam, including Why I Am Mot a Muslim; Nonie Darwish, author of Now They Call Me Infidel; Ayaan Hirsi Ali, author of Heretic; and Sohrab Ahmari, author of a book subtitled My Journey to the Catholic Faith. The ultimate public de-conversion took place in 2008, when Pope Benedict himself baptized journalist Magdi Allam during the televised broadcast of the Vatican Easter Vigil service.

Second, ex-Muslims organize. This phenomenon began in Germany in 2007 with the founding of the Central Council of Ex-Muslims. Since then, many similar groups have come into existence in Western countries with substantial Muslim immigration. The Ex-Muslim Organization of North America, for example, provides mutual support, polishes arguments against Islam, raises troublesome issues (such as female genital mutilation and polygamy), and actively lobbies governments. Again, Muslims have never before confronted such an opposition.

Thirdly, ex-Muslims argue against Islam to believers. Wafa Sultan in Los Angeles primarily addresses fellow Arabic speakers, finding fault with Islam and inviting them to leave it. Zineb El-Rhazoui in France has a very prominent role along similar lines, as does Hamed Abdel-Samad in Germany. Brother Rachid in Virginia is the son of a Moroccan imam, an evangelical Christian, and has an international television program in Arabic. As this suggests, many ex-Muslims find they cannot just walk away from Islam, so justifying their actions and convincing others to follow takes on a central role in their lives.

Expositions by these knowledgeable and inspired ex-Muslims writers living in the West have sent shockwaves to their countries of origin. Historically protected by custom and law from any kind of criticism, Islam lacks defenses for such critiques: sputtering imprecations and cracking down tend to be the favored responses, rather than reasoned rebuttals; recall the Danish cartoons of Muhammad and the violent outrage they inspired. Even irony is prohibited. Anxious authorities ban criticisms; if that does not work, they jail the culprits. They even concoct Zionist conspiracies.

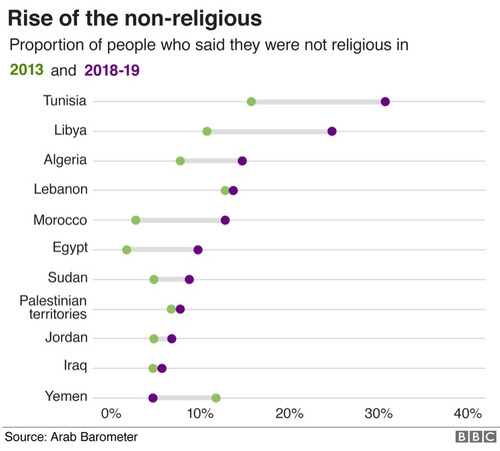

But with passion and unique authority, ex-Muslims push believers to think critically about their faith. These efforts have contributed to a substantial decline in Muslim religiosity. For example, a major survey called the Arab Barometer was summarized in The Economist the following way: “Many [Arabic-speaking Muslims] appear to be giving up on Islam.” This move toward secular outlooks across the Muslim world results in part from ex-Muslims in the West free to propagate their experiences and ideas.

As I said at the beginning, there’s never been anything like this in Islam’s 1400 years of history; it’s a new phenomenon. These boisterously opinionated ex-Muslims challenge their birth religion, helping both to modernize it and to reduce its hold. Their role has just begun, as their ranks increase and as pious Muslims flounder in the face of this challenge. The path will be interesting and unpredictable; I urge you to keep an eye on it.

_______________________

Question: Does the ex-Muslim movement have a role in the warming of attitudes in the Arab world toward Israel?

Pipes: Yes. Almost invariably, ex-Muslims are pro-Israel. I have yet to meet one who is not. Rejection of faith seems also to imply rejection of its politics. That’s not to say that ex-Muslims drove the Abraham Accords or other state-level changes, but they broadly impact public opinion and support the extraordinary development of the Muslim world becoming less hostile to Israel. Of course, plenty of Islamists and others still want to eliminate the Jewish state – I do not for a moment forget them. But overall, hostility towards Israel has gone substantially down, something the Abraham Accords reflect. As that happens, however, the global left has become ever-more hostile to Israel. So, Israel today has better relations with Saudi Arabia than with Spain or Sweden.

Question: Do ex-Muslims reduce the threat of radical Islam in the United States? What about terrorism?

Pipes: Yes, they do, not so much as informants (due to generally being excluded from Muslim life, especially once they’re public) but as translators, infiltrators for the police, and generally arguing against appeasing Islamism.

You may have noticed much less news about violent jihad in the United States. Two reasons explain this. First, counterterrorism has become far more effective, rendering a 9/11-style attack almost out of the question. Second, what I call the 6Ps – police, politicians, press, priests, professors and prosecutors – have made it harder to find out about jihad. When Islamist attacks take place, they tend to be portrayed as mere violent episodes without motive. Exceptions exist, such as Boston Marathon and Fort Hood attacks, but most of what appear to be jihadi attacks that are simply not reported, although these seem to take place every few months.

One example from 2013: an Egyptian Muslim in New Jersey murdered two Copts and butchered their corpses. The perpetrator, Yusuf Ibrahim, was caught, convicted, and rots away in prison. But never, not even at the court proceedings, did any hint of his motive emerge. Were the three young men fighting over a girl, over money, over loot, or over religion? Is Ibrahim a common criminal or a jihadi? I have been following this case for eight years and I have no idea. In all, I perceive less jihadi violence than there used to be but more than appears to be the case.

Question: Why does the author known as Ibn Warraq not use his birth name?

Pipes: Ibn Warraq means “son of the paper maker” and it was a name of a medieval skeptic of Islam. An Indian Muslim living in Europe, he published Why I Am Not a Muslim in 1995; that being shortly after the Rushdie affair, Khomeini’s edict prompted him to adopt a pseudonym. That was a quarter century ago; now Ibn Warraq is quite relaxed about his identity. I’m not going to state his real name, but it’s not that hard to discover.

He’s become a very significant scholar of Islam. Among other things, he has resurrected studies from before political correctness took over around 1980, bringing back scholarship from 1912 or 1865 that are otherwise forgotten, some in German that he’s had translated into English. It’s a remarkable corpus of information about Islam, the Koran, Muhammad, and so forth.

Question: I live in New Jersey, which has one of the largest Muslim populations in the United States. I’ve known Muslims all my life; I’m a teacher. I’ve had students tell me that they don’t believe anything about Islam, but they can’t make it public because if they did, their family members would kill them. There are many Muslims who don’t want to be Muslims. I ask you humbly, don’t criticize Muslims, they’re people just like us. The problems are in the belief system, the belief system of Islam.

Pipes: I accept your point and I do not criticize Muslims or Islam. I criticize radical Islam. I concur with your point about not criticizing Muslims as a whole, for they differ hugely among themselves. Likewise, I avoid criticizing Islam the 1,400-year-old religion that stretches around the world and takes many different forms, some more hostile than others. If you criticize Islam as a whole, what exactly are you criticizing? Also, I want to work with non-radical Muslims against radical Muslims, and criticizing their religion makes this much more difficult to do. I do criticize Islamism, a medieval, ideological, and radicalized utopian form of that religion.

Now, some of you may disagree with this distinction, arguing that Islamism is the only true form of Islam; fine, that is your privilege. But if you want to work effectively in American politics, you must make this distinction. Americans will not support a religious war and the U.S. government cannot fight a religion, only an ideology. You’re not going to get far by being anti-Islam; so I suggest you be anti-this radicalized form of the religion in public, if not in your heart.

Question: Doesn’t the Koran advocate pretending to be the friend of infidels until you get to a point when you can eliminate them?

Pipes: It does. But I warn against excerpting a bit in translation and saying, “Aha, this is the Koran.” The Koran is an extremely complicated and self-contradictory document. It is understood in different ways by different readers at different times. I once studied the Koran in Arabic with a sheikh in Egypt. In the course of several months, we covered only a few pages. Beyond the textual complexity, there’s the vast range of interpretations. It’s a big book and you can accept a specific part, reject it, or even reverse it.

I have devoted an article to interpreting the brief phrase “There is no compulsion in religion” and found nine alternate – and very divergent – interpretations of it through the ages and the continents. So yes, the Koran is a uniquely aggressive document, but be careful of reducing it to a simple command.

Part of reforming Islam is to interpret it in new ways, as every religion changes over time. Jews and Christians do this, and dramatically so. How can one be a pious Christian and endorse homosexuality? The Bible is very clear on this topic, but somehow or other, several denominations do so. How can slavery have been endorsed 150 years ago and now it’s universally an anathema? The same thing happens with the Koran. Muslims in ISIS or the Taliban adopt the most violent version, others adopt a moderate version.

Question: How do we distinguish the so-called radical Muslims from the regular Muslims?

Pipes: Muslims are of many different points of view, obviously, they’re not one bloc, with everyone thinking alike. Some Muslims are Islamists, radicals, utopians, seeking to apply the Sharia and build a caliphate, supporting ISIS, the Taliban, Al-Shabaab, Al-Qaeda, and so forth. They are the enemy.

But not all Muslims fall into that category. A growing number are firmly opposed to all of the above. I did not discuss why Muslims are de-converting but perhaps the most important reason has to do with their being horrified by Islamism. Many more remain Muslims. These are people we can and should work with.

As for how to tell Islamists from non-Islamist Muslims: that’s not easy. I have produced about one hundred questions for immigration officers but in ordinary life it’s a matter of intuition and experience.

Question: You say we need to work with Muslims, especially in politics. Don’t all Muslims share certain goals?

Pipes: Hardly. To be sure, they’re all Muslims and they all have the same Koran. Some aspire to an Islamic order, others do not. But, as I suggested earlier, interpreting the Koran differs from person to person, from group to group. Declaring all Muslims to be the enemy includes the 80 percent to 85 percent who are not Islamists with the 10 percent to 15 percent who are.

Lumping anti-Islamists together with Islamists or dismissing Muslims as all the same means giving up not just on an ally but on the key actor in a civil war taking place between Muslims. the main battle is between Muslims and we who are not Muslims are but auxiliaries. There are a billion and more Muslims, and we want to help those who are fighting the Islamists in a fight taking place nearly everywhere Muslims live.

I hope to work with anti-Islamists to help them get their ideas out by giving them platforms, applauding them, and providing them with funds so they can most effectively fight our fight against the radicals. I encourage you to help them too.

Question: Is radical Islam continuing to gain in strength?

Pipes: In general, no, though there are exceptions like Pakistan. Mostly, Muslims see what life is like under Islamist rule in Iran, in Sudan, in Turkey, in Libya and wherever you see an Islamist order. And they say, “No, thank you.” With time, then, more and more Muslims oppose Islamism. Islamism peaked about a decade ago. It began in the 1920s, peaked about 2012, and is now mostly in decline. In part, too, this results from infighting among Islamists.

Read the rest of the Transcript at DanielPipes.org.

[…] Supply hyperlink […]