The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, has emerged from his self-imposed period of silent reflection to declare that he is “utterly sorry” to victims and survivors of child abuse in the Church of England. He feels “a deep sense of personal failure” about not doing enough about the scandals that have so afflicted the Church in recent years.

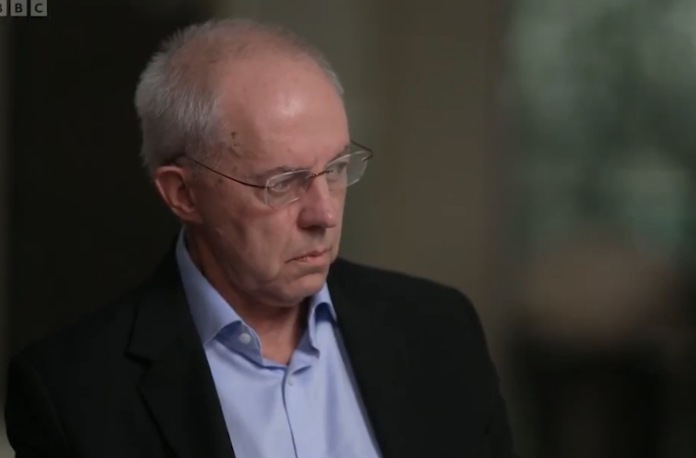

It is not the first time he has attempted to apologise for his failings, and it may not be the last, but there was, as with his past attempts to exculpate himself, still something deeply unsatisfactory about them. It is, indeed, difficult to know quite what Bishop Welby, as he now is, thought he would achieve by granting an interview to the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg. His expressions of remorse leave the organisation he so recently headed, with its 85 million “family” across 165 nations, hardly much better placed to face the future.

For a man to have risen so quickly to the top of the Church and then fallen so precipitously, Bishop Welby still seems to have difficulty with his sometimes unfortunate choice of language, which confirms the distressing lack of judgement that ultimately led to his demise. He is no doubt sincere in his Christianity but, particularly in deference to the victims and survivors of the serial abuser John Smyth, his plain declaration that he had forgiven Smyth – an immediate “yes” in response to Ms Kuenssberg’s query – could have been couched in a more empathetic manner, though he added it wasn’t about him but the victims. He comes across as a cold fish, even if he is not. The former archbishop’s mea culpa was, therefore, not quite as empathetic as it might have been.

Under invigilation by Ms Kuenssberg, he remains uncomfortable about the fact, freely admitted, that he had known, and known of, at least some of the allegations made against Smyth before and after he became Archbishop of Canterbury in 2013. However, Bishop Welby pleads, once again, that his regret about his lack of action in the Smyth case was because he did not know all the details until 2017. He repeated his line that he was insufficiently “curious” and not insufficiently “caring” and that he regretted failing to follow up on what turned out to be inaccurate information about a police investigation.

What remains missing is precisely why he was so incurious about Smyth, a man he knew. Implied, but not yet quite admitted, is that perhaps the then Archbishop Welby hoped the whole Smyth scandal and similar cruelties would just go away while he got on with more pressing matters. The stinging judgement of the Makin committee’s report into Smyth last year stands: “On the balance of probabilities, it is the opinion of the reviewers that it was unlikely that Justin Welby would have had no knowledge of the concerns regarding John Smyth in the 1980s in the UK […] it is most probable that he would have had at least a level of knowledge that John Smyth was of some concern.” The report also criticised the nature of Archbishop Welby’s subsequent outreach to the victims, also echoed by one prominent survivor in the BBC programme as a current issue.

What is new is Bishop Welby’s statement that the sheer volume and seriousness of the allegations that crossed his desk meant that he was so “overwhelmed” that he couldn’t deal with all of them and had to “prioritise”. That is surely the opposite of the correct response. If things were so bad out there, then some sort of inquiry should have been launched into this massive problem straight away. He also explained, fairly, that the police had told him not to interfere in live cases or legal proceedings, including against the appalling crimes of another, convicted, sex offender, Peter Ball, who’d risen to the post of Bishop of Gloucester. But those are not reasons to do nothing about the rest of the pile of allegations.

Bishop Welby stresses that none of this extra background to his lack of curiosity and fatal inaction constitutes an excuse, still less a justification, for his complacency, but he offers it by way of explanation. It remains partial and, thus, unsatisfactory. Bishop Welby sometimes seems almost to acknowledge that but cannot quite admit it publicly.

The lack of judgement exercised by Welby has proved enduring. It is just one apology after another. In his Kuenssberg interview, he even had to express regret about the defiantly jokey speech he made in the House of Lords after he had had to resign. He admits now that “it did cause profound upset, and I am profoundly ashamed of that […] I wasn’t in a good space at the time. I shouldn’t have done a valedictory speech at all.” Yet here he is, at it again.

The former archbishop has to live with the fact that he failed to stop the child abusers, failed to secure justice for hundreds of victims and survivors, and left the Anglican Church in an even weaker state than it was when he took over in 2012. That his wasn’t the only religious movement, or any other kind of environment, from Hollywood to politics, charities to the CBI, to have become scarred by sexual abuse scandals, is context but not full explanation. Yes, he was never, as he states, ever the “chief executive of the Church of England PLC” with untrammelled powers. There was only ever so much he could do.

But, for all his pleas in mitigation, the conclusion is that he and the governing General Synod have not even now implemented the kind of statutory duty to safeguard vulnerable people or the process of an independent investigation that might restore faith in the Church and prevent more children from having their lives ruined. That may sound harsh, but it is what Bishop Welby and the other leaders in the Church of England cannot quite bring themselves to concede, and it is wrong. As the Book of Proverbs has it, “pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall”.