Part 2. The Westminster Confession of Faith at odds with the theology behind the Prayer Book

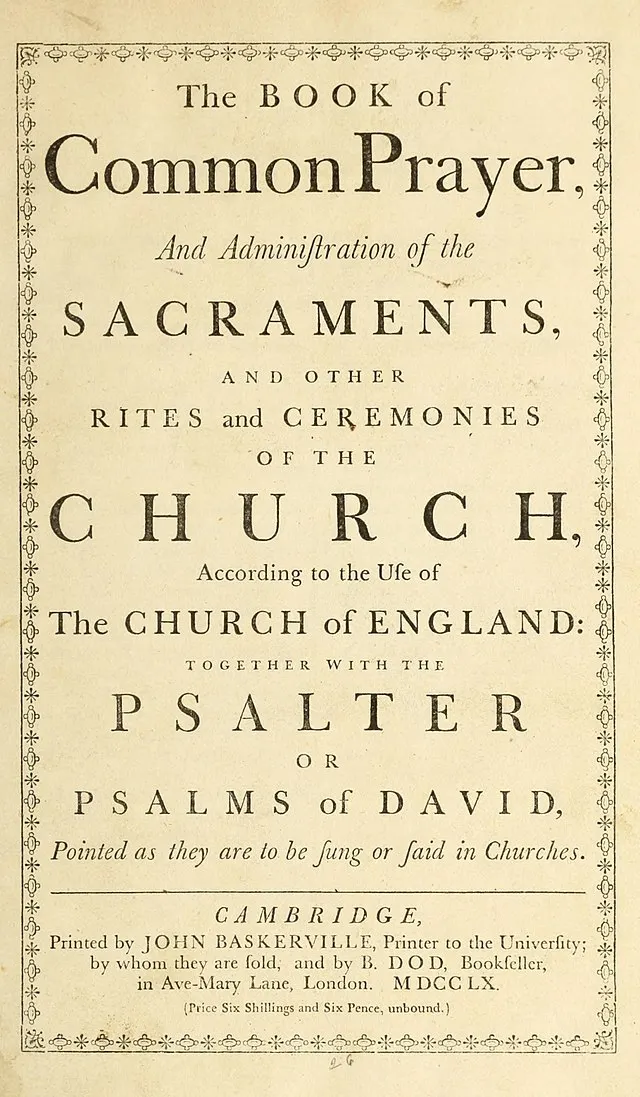

The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is a cornerstone of Anglican identity and one of the Church’s foundational formularies. More than a liturgical manual, the BCP articulates the theology of the Anglican Church in its prayers, rites, and rubrics, reflecting the faith and order of the undivided Church. Its pages convey a deeply sacramental vision of the Christian life, rooted in the mysteries of grace and the apostolic tradition. The BCP preserves the orthodox faith, affirming doctrines such as the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the necessity of sacramental grace for salvation, and the Church’s role as the visible Body of Christ on earth.

In the 17th century, the integrity of Anglican orthodoxy, as expressed in the BCP, faced a serious challenge from the rise of Puritanism and its theological manifesto, the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF). The Puritans, seeking to reform the Church of England according to their vision of theology, viewed the BCP as an obstacle to their efforts. For them, its sacramental theology, hierarchical ecclesiology, and reverence for the liturgical tradition were incompatible with their emphasis on predestinarian soteriology, the regulative principle of worship, and an aversion to anything they deemed “popish.”

Figures such as George Gillespie, a leading architect of the Westminster Confession, openly attacked the BCP, accusing it of fostering idolatry and superstition. The campaign against the theology of the BCP was not merely a matter of preference but an attempt to dismantle the theological framework of Anglicanism itself, replacing it with a system that rejected the sacramental grace and liturgical reverence central to the Church’s catholic identity. Had the Westminster Assembly fully succeeded in implementing its vision for the Church of England, it would have risked severing the Anglican Church from key elements of its apostolic heritage, jeopardizing its continuity with the orthodox faith as it has been faithfully handed down through the centuries

This article will examine the theological conflict between the BCP and the WCF, demonstrating how the BCP safeguarded the Church’s catholic and apostolic faith against the errors of Puritanism. By exploring the arguments of Gillespie and looking at the directory of public worship, it will highlight the theological depth of the BCP and its indispensable role in preserving the orthodox faith within Anglicanism.

The Prayer Book Under Siege

The Book of Common Prayer, a cherished expression of Anglican piety and theology, became a target during the debates of the Westminster Assembly. While some sought to abolish it entirely, others desired to remove its ceremonial elements and practices, which they deemed unscriptural. This is the major point of contention. This was not merely a matter of preference but reflected a deep theological divide over the nature of worship and the Church’s authority. This is due to the Reformed doctrine of the Regulative Principle of Worship which believes one should worship only in ways that are explicitly supported by Scripture: “or ways which are derived thereof from good and necessary consequence;” 1 Additionally the WCF did not advise the use of the BCP’s long form responsive elements in public or private prayer including its ceremonies:

Howbeit, long and sad experience hath made it manifest, that the Liturgy used in the Church of England, (notwithstanding all the pains and religious intentions of the Compilers of it), hath proved an offence, not only to many of the godly at home, but also to the reformed Churches abroad. For, not to speak of urging the reading of all the prayers, which very greatly increased the burden of it, the many unprofitable and burdensome ceremonies contained in it have occasioned much mischief, as well by disquieting the consciences of many godly ministers and people, who could not yield unto them, as by depriving them of the ordinances of God, which they might not enjoy without conforming or subscribing to those ceremonies.2

George Gillespie, one of the staunchest Puritan voices at the Assembly, was unequivocal in his critique of the Prayer Book’s ceremonies. He argued that they were “idolatrous” and introduced corruptions into worship, stating:

“In the pretended communion, it hath all the substance and essential parts of the Mass, and so brings in the most abominable idolatry that ever was in the world, in worshiping of a breaden God, and makes way to the Antichrist of Rome, to bring this land under his bondage again, as may be seen at large by the particulars of that communion, wherein some things that were put out of the service book of England, for smelling so strong of the Mass, are restored, and many other things, that were never in it, are brought in, out of the Mass book, though they labour to cover the matter.”

3

Gillespie writing against Bishop Andrewes in his work against what he saw was popish traditions that England had, wrote:

Bishop Andrews, speaking of ceremonies,4 not only will have every person inviolably to observe the rites and customs of his own church, but also will have the ordinances about those rites to be urged under pain of the anathema. I know not what the binding of the conscience is, if this be not it: Apostolus gemendi partes relinquit, non cogendi auctoritatem tribuit ministris quibus plebs non auscultat. And shall they who call themselves the apostles’ successors, compel, constrain and enthral, the consciences of the people of God?5

For Gillespie, the Book of Common Prayer represented an affront to the Regulative Principle of Worship, which held that all elements of worship must have explicit warrant from Scripture. Gillespie went further, critiquing specific practices such as the sign of the cross in baptism, kneeling at Holy Communion, seeing them as superstitious and, as he claimed, innovations that lacked a solid foundation in the sacred text. He regarded such rites as vestiges of Romish corruption, imported into the Church of England under the guise of piety, but ultimately serving to obscure the simplicity and purity of worship as prescribed by Scripture alone, saying:

“Oh thou best beloved among Women what hast thou to doe with the inveagling appurtenan∣ces and abilement of Babylon the Whoore?—But among such things as have beene the accursed meanes of the Churches desolation, those which peradventure might seeme to some of you to have least harme or evill in them, are the Ceremonies of kneeling in the act of receiving the Lords Supper, Crosse in Baptism, Bishopping, Holy-dayes, &c. which are pressed under the name of things indiffe∣rent.”6

Defenders of the Prayer Book

Anglican defenders of the Prayer Book responded with both vigor and eloquence to these critiques. Archbishop Laud, though a polarizing figure, spoke with notable clarity regarding the Prayer Book’s role in maintaining continuity with the historic Church, even while it retained certain elements from Rome. He argued:

“For the other stuff which fills up this argument, that these ‘changes and supplements are taken from the Mass-book, and other Romish rituals, and that by these the book is made to vary from the Book of England;’ I cannot hold it worth an answer, till I see some particulars named… I would have them remember that we live in a Church reformed, not in one made new. Now all reformation that is good and orderly takes away nothing from the old, but that which is faulty and erroneous. If anything be good, it leaves that standing. So that if these changes from the Book of England be good, ’tis no matter whence they be taken. For every line in the Mass-book, or other popish rituals, are not all evil and corruptions. There are many good prayers in them; nor is anything evil in them, only because ’tis there. Nay, the less alteration is made in the public ancient service of the Church, the better it is, provided that nothing superstitious or evil in itself be admitted or retained”7

Lancelot Andrewes, a learned and devout servant of the Church, did not shrink from defending the holy rites and ceremonies, even unto their most reverent observances. In his sermons, as in his writings, he ardently upheld the practice of Eucharistic adoration, proclaiming with great earnestness that this sacred act, though veiled in mystery, is a fitting homage to the divine presence. He spoke:

Adoration is permitted, and the use of the terms “sacrifice” and “altar” maintained as being consonant with scripture and antiquity. Christ is “a sacrifice—so, to be slain; a propitiatory sacrifice—so, to be eaten.”8

Jeremy Taylor rejected the Puritan charge of idolatry, insisting that outward gestures such as kneeling were acts of humility rather than superstition:

“Externall worshippings are expresse acts of duty, and subordination to the person worshipped. Thus to be uncovered in these Westerne parts is a tendry of our service, and ever was since donare pileo was to make a free man of a slave.”9

Richard Hooker, who was later combated against by George Gillespie, wrote against the rise of puritanism in his day, passionately defending the Prayer Book’s role in preserving unity and devotion:

” In the fifty-fifth Psalm, David says, “We took sweet counsel together, and walked in the house of God as friends.”” He is telling us that when we meet together and go to the house of God together we should be united by a bond of indissoluble love. We can hope that there is such a unity of the people with each other, and of the pastor with his people, and of the pastor with each one of his people. This happens when in the hearing of God and in the presence of his holy angels there are common songs of comfort, psalms of praise and thanksgiving and common petitions to God. The unity is produced when the people are all of one voice. When the pastor makes a petition in their behalf, with one voice they give their assent and say Amen. At other times they join together with him in common prayers.”10

Richard Hooker, in the same work, also writes against the Puritan’s view on how the English Church views Rome. He believed:

Those of the Roman obedience are Christia and many in- sights on their part are insights Christianity itself. Roman Catholic insight into liturgical matters has often been significantly sound and worthy of our consideration. The great liturgical scholars of the Church of Rome have frequently been our guides. Where they are wise and Christian it is well to follow them. Often, however, those of the Roman obedience are wrong. There has been a superstitious development in certain liturgical usages of the Roman Church. That needed reformation.11

Continuing on Hooker believed the English Church follows Rome and looks to her as a guide in many of their liturgical customs:

We place prayer above the sermon, and often have daily offices in our churches without any sermon at all. In this respect we follow the Church of Rome. Those who support a reformation that would completely destroy the old order, wish a sermon and a minimum of prayers. The prayers would then be for the purpose of stirring up the congregation to listen to the sermon. We, on the other hand, hold that the Church of Rome is right, and appoint a service which the clergyman is bound to observe and cannot dispense with. 12

Read it all at the Way of Walsingham