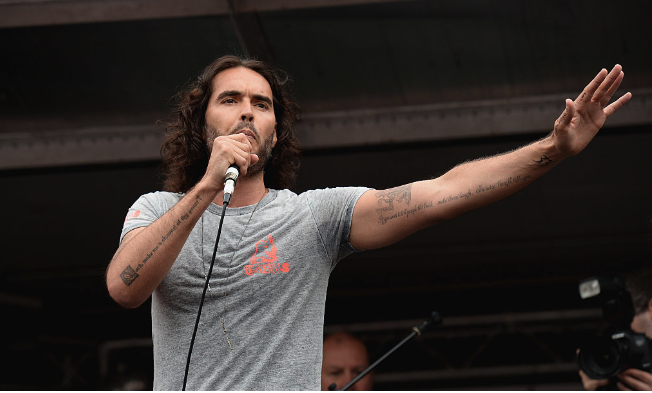

Is he the messiah? Or just a very naughty boy? Since Russell Brand found Jesus he hasn’t stopped talking about it, whether on TikTok, or Tucker Carlson’s live show, or while baptising other men in a lake while clad only in his tighty-whiteys. Then, over the weekend, he and Jordan Peterson led a crowd of 25,000 outside the Washington Monument in the Lord’s Prayer as part of the Rescue the Republic gathering.

Perhaps it’s all showbiz. Or perhaps all these putative messiahs are signs of the End Times. Certainly the idea that the American Republic needs rescuing at all — let alone with prayer — suggests there’s an apocalyptic mood afoot. Last Sunday, even Donald Trump — not renowned for his piety — got in on the game, posting the Catholic prayer to St Michael on X.

Beneath all the internet showboating, a deeper vibe shift is under way in the relation between men and religion. For a long time, this relation has been shaky, with the “feminisation of Christianity” a longstanding complaint and amid a deluge of books on why men are quitting church. Now, if St Michael is triggering controversy on Trump’s X account, this is part of a larger picture: the return of Christianity in a masculine key. And it isn’t just celebs and politicians: last week, The New York Times reported that young men are turning to the Christian faith in markedly greater numbers than young women, who are more likely to embrace the fluffier doctrines of progressivism.

What is happening? Is this just another aspect of the more widespread politicised sex war? Perhaps this contributes, but I think it goes deeper. Two interlocking patterns are contributing to the new macho Christianity: firstly, that the world in general is growing more disorienting, extreme, and uncanny. This is spurring a widespread sense of existential spiritual conflict, in which post-war Christianity simply doesn’t cut it any more. And, secondly, young men conditioned by video gaming to pour all their energy into dematerialised battles have responded to this new disorientation, by extending their interest in ideational war beyond gaming to the fabric of reality itself.

It was Friedrich Nietzsche who kick-started the modern backlash against Christianity, claiming in Beyond Good and Evil (1886) that it was a creed of slaves which exerted a stifling, feminising downward pressure on individuality, energy, and self-confidence. Three decades later, the First World War drove many ex-soldiers to agree with him that “God is dead”. But it wasn’t until 1945 that this germ of mass unbelief flowered in earnest, in the mushroom-clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki: world-shattering events that, as the Catholic writer Ronald Knox described at the time, felt for many like the decisive triumph of secular science and a Godless universe over the divine and loving order of Christian tradition.

If the atom bomb seemed, to Knox, an existential threat to faith, it also seemed for many to represent the end of war. How could war even start, between industrialised nations, when its conclusion might be another Hiroshima? Under the shadow of mutually assured destruction, then, both Christian belief and the value of “manly” courage and martial vigour came to seem as though they no longer had anything to offer the world. Amid the smoking civilisational rubble this left us, it seemed to many as though the only safe place for Christians to stand was not for anything that might raise an enemy against you, but on the side only of peace, welcome and safety, and the deification of “the vulnerable” and “the marginalised”.

The brouhaha over Trump’s post was partly in response to just how starkly the warrior archangel St Michael contrasts with this post-war sensibility. Most representations of St Michael show him subduing a dragon, understood to represent the Devil, while his prayer implores St Michael to “defend us in battle”, and to “thrust into hell Satan, and all the evil spirits, who prowl about the world seeking the ruin of souls”. This is a combative style of faith long deprecated by the modern Christianity of universal niceness.

“The brouhaha over Trump’s post was partly in response to just how starkly the warrior archangel St Michael contrasts with this postwar sensibility.”

And I suspect it’s returning for a straightforward reason: secularism as such is collapsing and everyone — even the avowed secularists — are already behaving as though we’re in a spiritual war. Even the objections to Trump’s post, for example, have this febrile quality of spiritual battle about them. One notable Trump hater interpreted the Michael post literally, as evidence that Trump views Kamala Harris as an evil spirit who needs to be “thrust into hell”, calling this “terrifying”. And a still more striking instance of the now increasingly pervasive post-post-religious weirding came from one of its most staunch opponents: James Lindsay. Lindsay, the co-author of a 2020 book critiquing “woke” academic theories as threats to Enlightenment values, worried that Trump has been manipulated into name-checking the Archangel Michael by “Operation Michael”. This, we are to understand, is part of an occult plan concocted by the Theosophists who run the UN and something called the Fetzer Institute, to channel the Archangel to bring about and control the next stage of spiritual evolution via something called Social-Emotional Learning.

The fact that even so staunch a defender of the Age of Reason is now mounting that defence in terms I can only describe as barmy suggests forcefully that his cause may already be lost. And this is thanks to our high-tech age. In part, as I argued last week, it’s because this teaches us to visualise complexity but not how to control it, encouraging a deification of natural forces such as “climate”. But it’s not just weather gods: it’s also those demons that might or might not be real, and which we meet in our own information machines.

Ideas, images, and even policies travel like lightning online, seeming to take on a life of their own. Groups of people define themselves through love or hate of any theme, idea, or individual you can think of. And sometimes an idea can appear so overwhelmingly powerful it seems to occupy everything and everyone at once: as though some ideas have us, rather than we them. Think of the weird way every alternative to lockdowns came to seem unthinkable, even evil.

And as we’ve grown accustomed to watching memes travel and mutate like this, across millions of individual minds, it’s become less eccentric to imagine them as more than the sum of their parts: as though they have a “spirit” and agaenda of their own. Some will say this is just an illusion; or that we don’t know but it’s a useful shorthand to talk about “egregores”, meaning entities composed of multiple consciousnesses. From there, though, it’s only a short step to saying ideas or moods are aware in some sense, with agency and their own plans; at which point we might as well just call them “demons”.

Do that, and the world is suddenly very much weirder, and very much more alive. This isn’t just my overactive imagination: the slippage between metaphorical and literal demons is widespread. All the way back in 2014 Elon Musk warned that with AI we are “summoning the demon”, while more recent reports of unsettling interactions with AI chatbots suggest some are already entertaining the possibility that we have summoned it.

Read it all at UnHerd