In “Embrace Pluralism over Racialism,” Manhattan Institute president Reihan Salam rightly observes that “we are living through a disturbing rise in anti-Semitic violence.” From the nation’s first days, he reminds us, “America has welcomed the Jewish people,” who, in turn, “have helped make America the most dynamic, productive, and creative nation in the world.”

I would go further. As Paul Johnson wrote in his History of the Jews (1988), it is to the Jews that “we owe the idea of equality before the law, both divine and human; of the sanctity of life and the dignity of the human person . . . of collective conscience and so of social responsibility . . . of peace as an abstract ideal . . . and many other items which constitute the basic moral furniture of the human mind.”

In diagnosing the rise in anti-Semitism, Salam puts his finger on what he terms “racialism,” defined as “a new form of adversarial identity politics” that “scorns meritocratic pluralism” and has become all the rage, figuratively and literally speaking, among a demographically diverse cross-section of young adults.

As the old saying goes, an explanation is the place where the mind comes to rest. But if we dig deeper, might we find an inverse relationship between religious commitments and anti-Semitism, such that a decline in religion begets a rise in anti-Semitism?

A suggestive study released last year might lead one to consider that possibility. In “From the Death of God to the Rise of Hitler,” published in the Journal of Economic Literature, economists Sasha O. Becker and Hans-Joachim Voth subjected diverse datasets to cutting-edge statistical analyses to test whether Germans who lived in robustly Christian communities were more or less likely than otherwise comparable Germans to join the Nazi Party.

As Becker and Voth interpreted them, the results favored what they styled the “Shallow Christianity” theory: in places in which “the Christian Church only had shallow roots, the Nazis received higher electoral support and saw more party entry.” The “results,” they concluded, “suggest that Nazi support and Hitler’s startling appeal received an important boost from the spiritual ‘emptiness’ of large parts of the German population.”

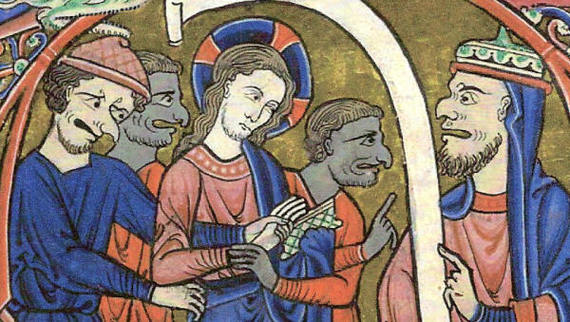

Still, positing an inverse relationship between robust religious commitments, especially among Christians, on the one side, and anti-Semitism, on the other, might seem ahistorical, or even ridiculous. After all, pre-Vatican II, my own beloved Roman Catholic Church was at times a marketer of anti-Semitic views.

For example, in his magisterial book, The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain (1995), B. Netanyahu, father of the present Israeli prime minister, chronicles how the Jews, after resisting the Church’s commands to convert, and being tortured and slaughtered for that resistance, started to comply. But it was not all coerced capitulation; rather, many Jews genuinely embraced the new faith, drenched as it was, then as now, in Hebraic-originated ideas, rituals, and symbols. Some Jews even became Catholic bishops. The Church’s ultimate response, however, was not to embrace but to expel its Jewish co-religionists, redefine “Jewish” as a racial category beyond the pale of conversion, and resume pogroms and persecutions (if “resume” is the right word, since, from 1391 to 1492, the anti-Semitic violence was nonstop).

More generally, to posit that a decline in religious commitments is implicated in the latest rise in anti-Semitic beliefs and behaviors might seem daft, given that so much of the phenomenon seems inextricably bound up with inter-religious conflicts between Jews in Israel and their fundamentalist Muslim neighbors in the surrounding countries.

All that acknowledged, it remains the case that the latest surge in anti-Semitic behavior is occurring in an America in which, over the last two decades, tens of millions of people, mostly of Christian background, have either broken with organized religion or become secular. The best book on the trend is David Campbell, Geoffrey Layman, and John Green’s Secular Surge: New Fault Line in American Politics (2021). More than a third of Americans now self-identify as belonging to no religion, and about three-quarters of them are now secularists, defined by Campbell et al. as people who disbelieve in the God of Abraham and affirmatively believe in “scientific naturalism . . . humanism, or freethinking.

Read it all at City Journal