36th Session of Provincial Synod

“ACSA Discipling Communities for a Changed World”

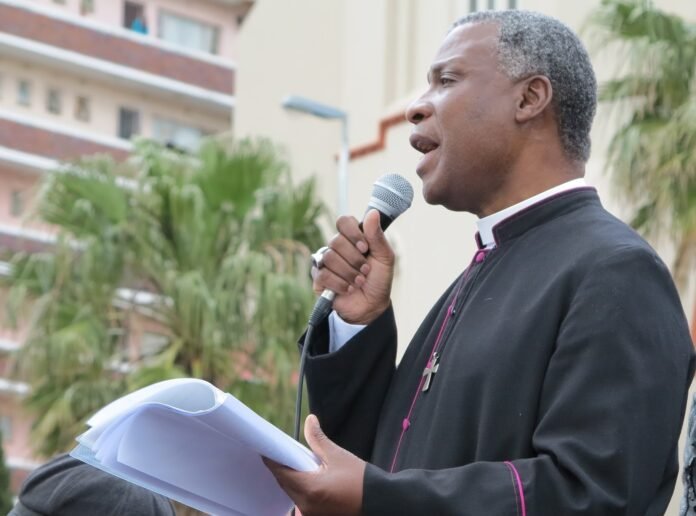

Charge by the President of Synod, the Most Reverend Dr Thabo Cecil Makgoba

Archbishop and Metropolitan

September 21, 2021

Readings: Proverbs 3: 9-18; Psalm 19; Matthew 9: 9-13

May I speak in the name of God who is Creator, Redeemer and Sustainer. Amen.

Welcome & Acknowledgements

Members of Synod, sisters and brothers in Christ gathered in your Diocesan hubs, members and friends of our church watching online, a very warm welcome to the opening Eucharist of this, the 36th Session of Provincial Synod.

A special welcome to those of you attending Synod for the first time. Although I will miss meeting you in person, I hope you will feel included and encouraged to play your full part in proceedings. I also want to recognise members of the Order of Simon of Cyrene and all our Provincial office-bearers, those with full-time jobs who give generously of their time and effort to the Church. Speaking about generosity, I encourage all members of Synod to give generously at the offertory, since your giving will support bursaries for theological education in the province. A report in the Addendum to the 2nd Agenda book emphasises the need for a Province-wide conversation on critical decisions that we need to make on re-imagining the training and formation of our clergy.

Since Synod last met in 2019, one bishop in service and several retired bishops have died. We recall the tragic loss to Covid-19 of Bishop Ellinah Wamukoya of Swaziland, as well as the deaths of Bishops Mlibo Ngewu, formerly of Mzimvubu, Tom Stanage, formerly of Bloemfontein, Edward MacKenzie, Suffragan in Cape Town, Merwyn Castle of False Bay, Eric Pike of Port Elizabeth, and Derek Damant of George. We acknowledge too the deaths of former members of Provincial Synod: Ms Agnes Mabandla, Dr John Healy, the Revd Malusi Msimango, the Revd KL Mashishi, the Revd Canon S Mupfudzapake and Mr Kenson D Qwabe. We also pause to remember clergy and their families, as well as the many others who have died due to Covid-19. May they rest in peace and rise in glory.

Also, since the last Synod, there have been a great many changes in the bench of bishops. I take pleasure in welcoming newly elected bishops to their first Provincial Synod in their new capacities: Bishop Nkosinathi Ndwandwe of Natal, formerly of Mthatha, Bishop Tsietsi Seleoane of Mzimvubu, formerly Suffragan in Natal, Bishop Luke Pretorius of St Mark the Evangelist, Bishop Joshua Louw of Table Bay and Bishop Vikinduku Mnculwane of Zululand.

We acknowledge with thanks to God the ministries of those who have retired or resigned: Sebenzile Elliot Williams of Mbhashe, Adam Taaso of Lesotho, Oswald Swartz of Kimberley and Kuruman, Martin Breytenbach of St Mark the Evangelist and Dino Gabriel of Natal.

For several bishops still in service, this will be their last Provincial Synod before retirement. We recognise the faithful witness and ministries of Bishop Andre Soares of Angola and Bishop Luke Pato of Namibia.

Church Governance under the Coronavirus

In the time of the coronavirus, we have faced considerable challenges in governing the church, from meetings of parish councils to convening synods and elective assemblies. Fortunately, hard work by IT specialists and our lawyers have guided us through the difficulties, and we will address some of the results as we work through the First Agenda Book.

As a result of the pandemic, we have been slower than we would have liked in filling episcopal vacancies and have had to rely much more than usual on Vicars-General during the interregna. However, we are beginning to overcome the backlog, and we congratulate the new bishops elected during this week by the Synod of Bishops: Bishop Brian Marajh of George, to be translated to Kimberley & Kuruman, and Dr Vicentia Kgabe, to be Bishop of Lesotho.

There has been a lot of comment about the number of elective assemblies in the past few years which have decided to delegate the election of a new bishop to the Synod of Bishops. Many rush to brand such a decision as a failure to elect, but as I told the Diocese of Natal recently, it is far from that. Of course, dioceses ideally want to make the decision themselves, and there is a proposal in the Second Agenda Book which seeks to address the matter. However, when a diocese chooses to delegate, I regard it as a spirit- and God-filled act. The Synod of Bishops takes the invitation to elect very seriously – and of course God can also work through the Synod of Bishops!

Igreja Anglicana de Mocambique e Angola

In the realm of church growth and church governance, the most exciting development to come before this session of Synod is giving birth to a brand-new Anglican province in Southern Africa – the Igreja Anglicana de Mocambique e Angola. When I addressed Synod in 2019, I said one of my hopes and visions was that “one day in the not-too-distant future we will inaugurate a new Province in the Communion: an independent, stand-alone, Portuguese-speaking Province in Southern Africa.”

Even I did not imagine that the dioceses in Mozambique and Angola would have been able to act so quickly. As a result of the intensive planning and work of Bishops Carlos Matsinhe, Andre Soares, Manuel Ernesto, and Vicente Msosa, supported by Mrs Mototjane in the PEO’s office, the PEO, the Revd Dr Makhosi Nzimande, the former PEO, Archdeacon Horace Arenz, Provincial Officers and our lawyers, we received the approval of the Communion for a new Province in August. On September 1, the day on which we commemorate Robert Gray, we adopted the Canons and Constitution, and on Friday IAMA will be inaugurated, with Bishop Carlos as the Acting Presiding Bishop and Bishop Andre as Dean of the Province. And all this has been done virtually, efficiently, and cost-effectively. Their hard work is an example to us all.

Of course, it is a bittersweet moment for ACSA. The Diocese of Lebombo was established in 1893, and these important dioceses of our Province have enriched our lives immensely over the past century. Now, in a part of God’s vineyard in which there were four dioceses a few months ago, there will soon be 12, with nine now. Next year, God willing and Covid-19 permitting, we will hold the re-scheduled Lambeth Conference. If it can indeed go ahead, we can be proud and pleased that our part of the world will be represented by not one Province but two. Praise be to God.

Discipling Communities for a Changed World

Across all the countries of the Province, the last 20 months have been as challenging as any through which any of us have lived. They recall the memorable words of the English novelist Charles Dickens, who writes in the opening paragraph of “A Tale of Two Cities”:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way…”

Our personal lives, our deepest relationships, have felt both horrific spikes of violence and destruction, but also the kindness of strangers as people have reached out to give succour and refuge to others. We traversed through a winter of despair when those already living in chronic poverty took on new burdens as unemployment spiralled. Hunger has haunted the faces of children. Domestic violence has scarred the lives especially of women and children. Both in South Africa and across the Western world we have witnessed the spectre of racism. The phrase “I can’t breathe” became the grim reminder of both the pandemic of racism and of the virus. We have heard cries for greater democracy on the streets of eSwatini, we have seen devastation and unparalleled violence in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. We have heard the echoes of the incessant bombardments of war in Cabo Delgado. Amid it all, the pandemic has ravaged our lives and livelihoods. We have experienced vaccine nationalism, in which the prosperous countries of the world have hogged life-giving inoculations, and we are still experiencing some vaccine hesitancy, despite the magnificent work being done by ACSA’s Covid-19 Advisory Team under the leadership of Canon Rosalie Manning.

During this Synod, one of the most controversial issues we will debate is whether vaccinations should be made mandatory, which is a sensitive issue not only here but across the world. Anti-vaccine lobbyists defend their right not to be vaccinated, which is all well and good if they are willing to stay at home in isolation. But as soon as they move into spaces occupied by others, their rights become limited by the rights of others. In the words of the legal philosopher Zechariah Chafee, “Your right to swing your arms ends just where the other person’s nose begins.” In a deadly pandemic, the right of your neighbour to life inevitably circumscribes your right to do as you like.

In the church, there is a strong case for clergy to be vaccinated because we are necessarily near other people, we visit vulnerable people to provide pastoral care and numbers of people in our congregations are vulnerable by virtue of age or comorbidities. The labour writer Terry Bell has put forward a powerful case for employers to make vaccinations compulsory, citing the cardinal principal of trade unionism, “an injury to one is an injury to all”. And is it expecting too much to require travellers sitting near others on aircraft flights to be vaccinated? Let us take seriously our prophetic role in society when we debate this matter.

In this time of suffering, unprecedented in its nature in the last hundred years, we have often felt bereft of answers and struggled to remember that tremendous reassurance that the Lord is with us. We have often felt the burden of failure, but we have also been encouraged by Madiba’s exhortation: “Do not judge me by my successes, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again.” In the words of St Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 11th century, we are indeed passing through an hour of “faith seeking understanding”.

As we try to get up on our feet again, as we look to our faith in groping towards understanding, we can take encouragement from today’s Gospel reading. The parallels between the age in which Matthew lived and our own reality are stark. His work as a tax collector put him into a particular category of people in a deeply unequal society. Scholars tell us that two percent of the population at the time of Jesus comprised the ruling elites. Another five percent were people like Matthew – retainers or agents who served the elites and the Roman Empire. Ninety-three percent were the poor, the peasants, those excluded from the benefits of the economic system, a system built on their labours.

Those figures call to mind statistics which Moeletsi Mbeki gave us at a seminar at Bishopscourt a few years ago. At the top of the pyramid, he told us, there is an elite who earn more than R60,000 a month. They constitute less than half a percent of working age people. Then there are independent professionals who make up two percent of the population, and a middle-class comprising just under 10 percent, who earn between R11,500 and R60,000 a month. Against that, 38 percent or nine million people are blue collar workers earning less than R11,500 a month, while 50 percent of working age people – a total of 12 million South Africans – are either unemployed or part of what he described as an “under-class”. Recently we learned another shocking statistic, that the official unemployment rate among people under 25 in South Africa is 46.3 percent, meaning nearly half of our young people have no jobs. The resolution on youth unemployment on our agenda could not be timelier.

The organisers of the Camissa Project, the series of discussions on black theology being hosted by St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, portray the challenges of Covid-19 vividly. “Race, class, gender and disparities were starkly exposed,” they say. “The frailties of life and ongoing exploitation were displayed for what they were by the stroke of a pandemic. Oppressed people worldwide experienced this pandemic as yet another burden in addition to the pandemics brought upon them in five hundred years of imperialist invasions, colonisation, oppression, enslavement, and capitalist exploitation. Similarly, gender-based violence has been described as a pandemic, hugely exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.”

Palestine in the Roman era and Southern Africa today are worlds in which Jesus was and is now at home, populated by people battered from every side; people upon whom, in Matthew’s words, Jesus looks compassionately for “they were like sheep without a shepherd”; people crying out for shepherds to raise their voices, to speak prophetic words, to instil hope and to work for justice. It is worth noting that Jesus’s invitation to Matthew was to leave the space he occupied as a tax collector. It was a challenge that reminded Matthew that a system which was built on corruption, that robbed the poor, that created desperation as a matter of course, was no place to find growth or fulfilment, no environment for becoming fully human.

Scholars tell us that Matthew’s Gospel is deeply influenced by Jeremiah and Ezekiel. When Jesus looks on the marginalised, he does as the prophet Ezekiel also did – he admonishes those who abuse their leadership for their own interests and protect ill-gained wealth or prestige. Hear the words of Ezekiel:

“Ah, you shepherds of Israel who have been feeding yourselves! Should not shepherds feed the sheep? You eat the fat, you clothe yourselves with the wool, you slaughter the fatlings; but you do not feed the sheep. You have not strengthened the weak, you have not healed the sick, you have not bound up the injured, you have not brought back the strayed, you have not sought the lost, but with force and harshness you have ruled them.”

Rowan Williams, in his new book, “Candles in the Dark: Faith, hope and love in a time of pandemic”, has pointed to how Covid-19 can offer us a way forward into a world which better reflects the values of Jesus. He writes that the pandemic has turned upside down the belief, especially among the affluent, that humankind is steadily bringing our environment under control. Instead, the pandemic has created what he calls a “new and unwelcome solidarity in uncertainty.” He continues:

“The Christian gospel repeatedly tells us that we are always involved in a situation of shared failure and shared insecurity; it tells us that this is overcome only when we stop denying it by closing our hearts to each other; and it announces that our closed hearts can be and are broken open to each other through the action of God in Jesus and the Spirit.”

And he adds that in the time of the virus:

“Perhaps we have learned more about our dependence on one another; perhaps we have learned something of the need to accept the limits and risks of living in a world we are never likely to tame successfully and totally. Or perhaps we have had our eyes opened to who is least safe in our neighbourhood – and not just our immediate neighbourhood, but our global neighbourhood…”

In this time of an ongoing pandemic, as we work out what it means to “disciple our communities for a changed world”, as our Synod theme says, if we have learnt anything, then it must be that we must use our gifts, rekindle our imaginations, harness our spiritual energies, and employ our skills, to choose again that fundamental option for the poor. As the story of the call to Matthew reminds us, it is never too late to leave our old ways and follow Jesus into implementing the Kingdom.

Choosing to focus on the poor and the marginalised has implications for how we organise our lives as the Church. I have occasion to meet with the Provincial Treasurer to pray and reflect on challenges that confront the Province broadly and some Dioceses specifically. Covid has made this time of reflection important particularly given the financial strain that many dioceses are experiencing. With so much change taking place in the secular world, both locally and internationally, we as a church need to begin a process of re-imagining ourselves, how we can remain relevant in a very changed world and meet the needs of our people. It is a time to look to our roots – at that which made us the Anglican Church in Southern Africa. We need to look to our clergy being well trained, not only ahead of their ordination, but beyond – with a strong emphasis on life-long learning. Looking at leadership development at all levels of the church, we must not lose sight of our role as servant leaders. We need to look to our laity and their gifts and skills and how they can assist the church to deal with the complexity of so many areas of church life – management, finance, property, education, leadership training, medical, legal, and so many more diverse disciplines. For our Bishops we need to remember that we are the servants of the servants of Christ and that we have a pivotal role in shaping the dioceses that we lead through our prophetic witness, building on the work of our predecessors and leaving a legacy of growth in mission and ministry and in the sustainability of our dioceses.

Choosing the option for the poor also has implications for our prophetic ministry to the world beyond our stained-glass windows. I have previously spoken of my participation a few years ago in the first Ecumenical School on Governance, Economics and Management in Hong Kong. At that meeting, four major international Christian groups – the World Council of Churches, the World Communion of Reformed Churches, the Council for World Mission and the Lutheran World Federation – brought together theologians, economists, church leaders and others to discuss how we can develop a new form of global governance and a new economic model, one that transforms the market economy from a self-serving mechanism for elites to one which is less exploitative, one which distributes resources and income more equitably, and which serves both our environment and all the world’s people.

Ahead of COP26, the forthcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, we are called to re-evaluate our relationship to our environment, and I am pleased to see that Synod representatives have put the issues of plastic pollution and the future of gas and oil exploration on our agenda. I was struck recently by the strong words used by Professor Jeffrey Sachs, one of the world’s top experts on sustainable development, at a recent meeting. He said the world’s food system is based on large multinationals and private profit, and on what he described as “the extreme irresponsibility of powerful countries in regard to the environment, and a radical denial of the rights of poor people.” In the 1980s, when the fight against apartheid reached its peak, many of us adopted the Kairos Document. It recognised that South Africa had reached a “kairos” moment – a moment of truth, a critical turning point – requiring a deeper commitment to the struggle. Today the climate emergency offers us another Kairos moment – an opportune moment for new and creative initiatives towards a just solution to the crisis.

In these frightening times, the Lord calls us to re-imagine our economies, to put people before profits, to enhance a sense of belonging and to repair the frayed social fabric of our communities. Part of repairing that fabric must involve intensifying our efforts to eradicate the scourge of gender-based violence. I have written in my memoir, “Faith & Courage”, of my first exposure as a priest to the depths of depravity that men can sink to, when I volunteered at a shelter for woman victims of violence in Johannesburg and witnessed the horrifying cruelty men can inflict on women.

Turning to the issue of how this affects us within the Church, one of the most difficult exercises in providing spiritual ministry is to learn to listen and hold space open for those who are hurting. In the Province our Safe and Inclusive Church Commission has helped us to do this even at the most difficult moments. We have amended the Canons to ensure that we can deal with abuse more transparently. Now we need to amend them also to help us challenge patriarchy and its values and practices within the church. It is not only critiques of our behaviour that will bring change; we need sustained teaching and modelling of an ethic of care and dignity (what we call “Seriti” in Sepedi) until everyone is free and safe, and treated equally in all our churches.

The societal challenges that we face are daunting, but we can respond to them in faith and hope. After the unrest in parts of South Africa in July, one of the acts of hope we saw emerged from people who found solidarity with each other and began to demonstrate against looters and rioters, to declare “not in my name” and to help clean up in the aftermath. It was a small beacon of hope, the kind of hope that Jurgen Moltmann spoke of in book. “Theology of Hope”, as “forward looking and forward moving, and therefore also revolutionising and transforming the present.”

We are called to be a church for such a time as this, shepherds for such a time as this. But when we hear the call of Jesus, we need, like Matthew, to follow quickly. It is part of the genius of Matthew that he also points us to practical ways of transforming lives to guarantee us a welcome in heaven, for example in Chapter 25. And he challenges not only the elites and the retainers; although they have a greater responsibility because they have resources and power, all of us, the 90 percent, have the responsibility to carry out compassionate ministries, to act with justice and to contribute to a different, transformed world. Every sheep is also a shepherd. No one is exempt from being part of ushering in the Kingdom. All of us are challenged to enhance the agency of the poor. That is what it means to be salt and leaven.

In many ways the Church in these challenging times hears the echoes of Jesus’ request to his friends on the night before he died, to watch with him. As we know, he was asking his friends not only to stay awake but to pay attention to the depths of reality. The English theologian Oliver O’Donovan points out that although the psalmist and the Old Testament prophets regularly call on God to wake up, this call is never sounded in the New Testament. The call there is instead that we should stay awake to God, that we should be alert to God’s work in the world. O’Donovan writes: “God has already awakened, has already acted. All that remains now is for the faithful to be awakened.”

Amid all the joys and sorrows, the hopes, and anxieties of our times, we are called to alertness, to mindfulness and to train our hearts to embrace the times and places when the glimpses of God appear. That surely is the task of the Church, just as it was for the disciples in their challenging hour, “to watch and pray’. And then, as with Peter, to feed the sheep. Every local congregation, big or small, every group, every individual occupying a pew, is both sheep and shepherd, and it is synergy which embraces both roles that will release the energies, creativity and discernment that will take our church forward confidently into the world that lies ahead. Let us use this Provincial Synod to equip us to take that journey.