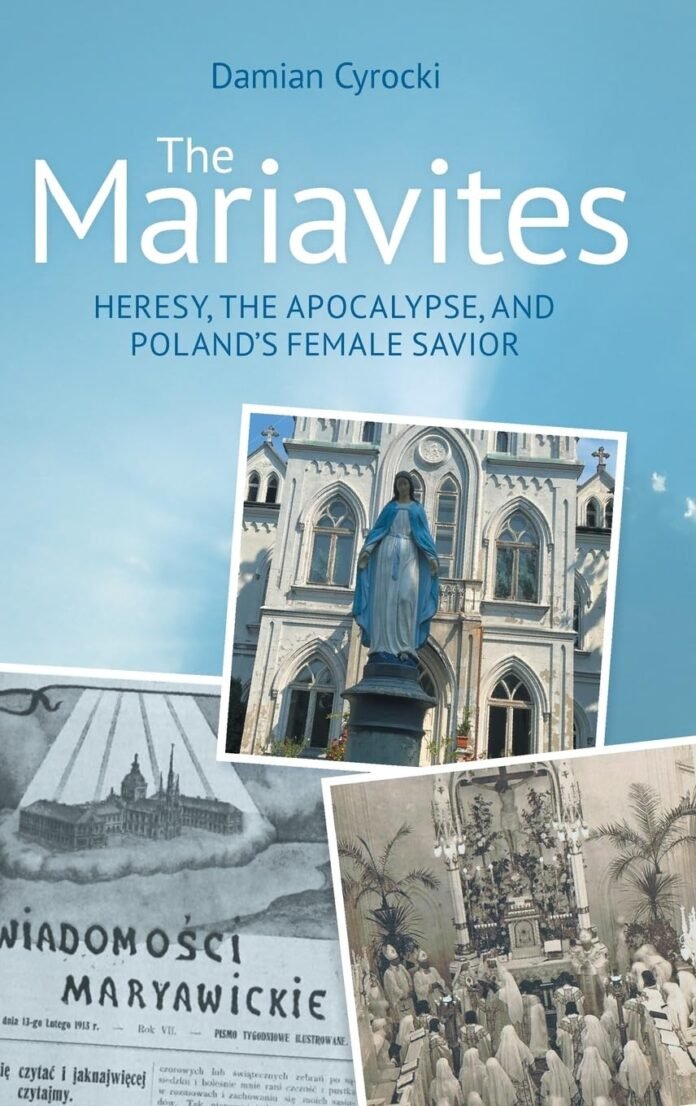

Imagine a Kingdom of God where peace reigns, criminals are punished only by love, and everyone speaks Polish—not Hebrew, not Latin, but Polish. This is no utopia conjured by a novelist, but the real-world vision of the Mariavites, a Catholic splinter group that has persisted for over a century in Poland and abroad, and keeps some 20,000 devotees today. Damian Cyrocki’s new book, “The Mariavites: Heresy, The Apocalypse, and Poland’s Female Savior” (Sheffield: Equinox, 2025), is the first full-length academic study in English of this extraordinary movement. Until now, significant scholarship has existed only in Polish.

Cyrocki’s work is a direct corrective to Jerzy Peterkiewicz’s “The Third Adam” (Oxford University Press, 1975), a novelized account that blurred fact and fiction. Peterkiewicz (1916–2007) may have charmed readers, but Cyrocki offers something sturdier. He presents his text as “largely a polemic against Peterkiewicz’s work” (18), less easily read but more reliably sourced. The book, a lightly revised doctoral dissertation, includes long excursuses that demonstrate how Mariavite practices—scandalous to Polish Catholics—had historical precedents. From venerating a living saint to ordaining women and marrying priests to nuns, Cyrocki shows these were not unprecedented. Yet, it remains unclear whether the Mariavites cited these precedents or if they are Cyrocki’s scholarly findings. The flow of the narrative may be interrupted, but the reward is rich: a trove of information about the Mariavites and the world that birthed them.

That world was Poland, under Russian Czarist occupation at the end of the 19th century. The Catholic Church, custodian of Polish identity, was caught between Vatican caution and Polish dreams of independence. The failed uprising of 1863 had convinced Rome that rebellion was futile. Quiet endurance was the Vatican’s prescription. But Polish romantic messianism—mystical, apocalyptic, and often critical of the Church—envisioned Poland as a liberator of itself and the world. Thinkers like Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), Juliusz Słowacki (1809–1849), and Andrzej Towiański (1799–1878) shaped this vision. Only Towiański founded a new religious movement: the Circle of Good Cause.

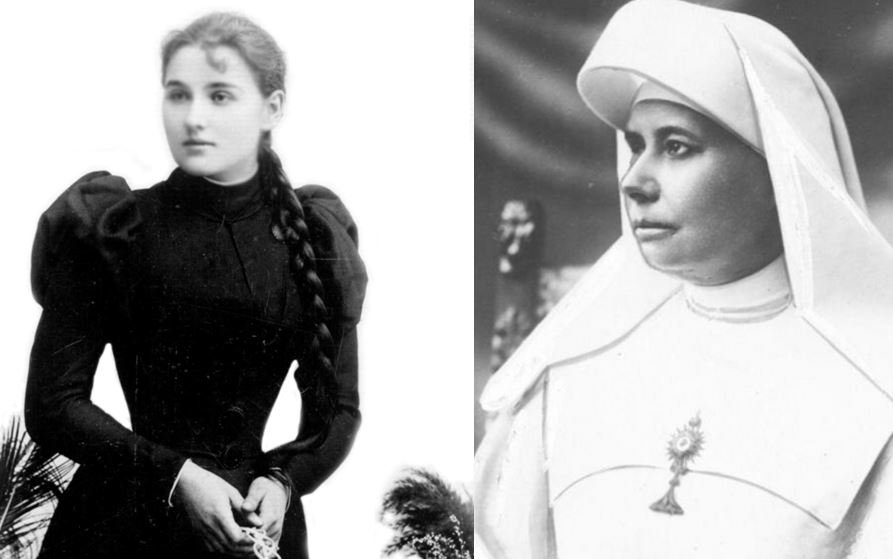

Cyrocki describes how Polish Catholics resisted Russian control through secret religious congregations. These had no legal status but operated in education and charity. The Vatican approved them in 1889, urging caution. The Capuchin priest Honorat Koźmiński (1829–1916), beatified by Pope John Paul II (1920–2005) in 1988, was their architect. He guided a young woman, Feliksa Kozłowska (1862–1921), fluent in four languages and devoted to chastity and service, through several congregational experiments. In 1887, she founded her own in Płock, known first as the Order of Saint Clare, then the Congregation of the Sisters of the Adoration. Known as Maria Franciszka and affectionately called “Mateczka” (“Little Mother”), she emphasized perpetual Eucharistic adoration.

In 1893, Kozłowska claimed a divine revelation: the world and clergy were corrupt, and she was entrusted with a “Work of Great Mercy.” This included devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, Our Lady of Perpetual Help, and the creation of new Mariavite institutions, including a congregation of priests. “Mariavite” is derived from “Mariae vita,” Latin for the “life of Mary,” which members were called to imitate. Cyrocki stresses that the revelation did not challenge Catholic orthodoxy. Other approved revelations, like La Salette, also criticized the clergy. Kozłowska’s push for frequent communion and Eucharistic adoration aligned with Vatican trends, though Polish conservatives disapproved. The real tension lay in placing priests under a woman’s authority—a rare but not unheard-of arrangement in Catholic history.

For thirteen years, the Mariavites operated as a Catholic movement. Some bishops opposed them; others supported. They appealed to Rome, with Jan Kowalski (1871–1942), later known as Maria Michał, a young priest who had joined the Mariavites in 1900, playing a key role. Pope Pius X (1835–1914) was initially sympathetic, but Polish bishops convinced Vatican officials that the Mariavites were heretical rebels. Kozłowska, meanwhile, continued receiving revelations, warning of Masonic infiltration in the Polish Church and even the Vatican. In 1904, Rome ordered the dissolution of the male Mariavite order. The Mariavites resisted. In 1906, Pope Pius X issued the encyclical “Tribus circiter,” condemning the movement. Kozłowska, Kowalski, and their followers were excommunicated.

What followed was a textbook amplification of deviance. Stigmatized, the Mariavites radicalized. They claimed that praying to Kozłowska was essential, as God had entrusted her with the world’s mercy. Though still self-identifying as Catholics, they sought legitimacy elsewhere. They tried to be legally recognized by Russian authorities. In 1909, Kowalski was consecrated bishop by the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands, part of the Jansenist-rooted Union of Utrecht, which rejected Papal infallibility. The Mariavites gained apostolic succession and built their own hierarchy.

In 1911, they began constructing the Temple of Mercy and Charity in Płock, a messianic beacon. In 1918, Kozłowska received a revelation that the valid Catholic Mass would soon cease. The Mariavites began recording names in a “Book of Life” —those who accepted the revelation and would enter the Kingdom of God on Earth, the centerpiece of Mariavite theology.

Kozłowska died in 1921, reportedly offering her life to preserve Poland’s independence from Soviet invasion. On her deathbed, she denounced Papal infallibility as blasphemy, but urged followers not to include her name in the “Hail Mary” or call her “Mother of Mercy”—that title belonged to the Virgin Mary. Kowalski ignored this caution. In 1924, he declared the Eucharist invalid in the Roman Church. He taught that Kozłowska was sinless and the earthly embodiment of the Holy Spirit—Jesus embodied the Son, Mary the Father. Reincarnation entered Mariavite doctrine, distinct from Eastern versions. Kowalski was seen as Archangel Michael incarnate, and by some, a second Christ. These teachings severed ties with the Old Catholics and the Union of Utrecht.

Kowalski’s innovations didn’t stop there. He allowed Mariavite priests to marry—but only nuns, not laywomen. Initially seen as mystical unions, they were sexual and produced children believed to be free of original sin and raised communally. Scandal erupted. Accusations of free love and polygamy flew. Cyrocki dismisses most as exaggerations and doubts the truth of sexual abuse charges that led to Kowalski’s imprisonment from 1936 to 1938. Yet, he quotes internal reports suggesting some local experiments with polygamy. Kowalski also ordained women as priests and bishops, eventually promoting the priesthood of all believers and stripping clergy of special status. He married Maria Izabela Wiłucka (1890–1946), a nun who became the first female Mariavite bishop.

Resistance brewed. In 1935, most Mariavite clergy deposed Kowalski and formed the Old Catholic Mariavite Church, retaining the Płock temple after litigation. They claimed fidelity to Kozłowska’s original vision, though Cyrocki notes this was no longer possible. They kept some reforms, like priestly marriage, with laywomen rather than nuns. Kowalski’s followers formed the Catholic Mariavite Church in Felicjanów, moving the “Book of Life” there. They numbered around 3,000, compared to over 30,000 in Płock. Both groups have since shrunk, but the ratio remains. A third, smaller group emerged—women who saw Kowalski and other bishops as divine incarnations. Though reprimanded, it also persists to this day.

World War II ended the legal battles. In 1940, Kowalski was arrested, sent to Dachau, and executed in 1942. His wife, Maria Izabela, succeeded him as bishop of the Felicjanów group. Both branches survived Nazi and Communist repression and remain active in Poland today.

Cyrocki underscores the Mariavites’ Catholic roots and their decade within the Church. He also traces later influences, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, whose literature Kowalski read with interest, although critically. Millenarianism is central, and Cyrocki highlights the historical vision of Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) as especially influential.

Cyrocki’s treatment is sympathetic but unflinching. Controversies are not hidden, but the conclusion is clear: the Mariavites, however maligned, deserve religious freedom and respect.