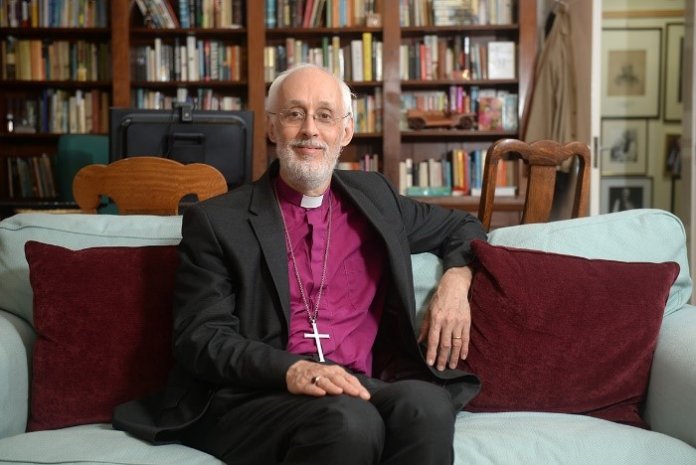

A proposed law to give terminally ill people in England and Wales the right to choose to end their life has been published. MPs will vote on the bill for the first time on Friday, 29th November. Ahead of this vote, Bishop David expresses his deep concerns about the bill in this article, which was originally published by the Manchester Evening News:

We prize individual freedom highly in our society, and rightly so. We don’t expect to be told not to do something unless it is clear how it will cause significant harm. Caring for a loved one in their final months, weeks and days alters us and can lead us to question if there is another way. Yet what we have seen, as the current Bill begins to come under scrutiny in Parliament, and as its advocates are subjected to questions in the media, is that the harms are real and the safeguards intended to prevent them are not up to the job.

My concerns echo those of many of the organisations that support people living with disabilities, along with many doctors and health professionals. They are supported by my Christian faith, which upholds that every human life is precious, but I share them with those of other faiths and none.

My first problem with the Bill is that it has no workable means of ensuring that an apparent decision to seek an assisted death is free of coercion. A sick and frail person is deeply vulnerable. When the time involved in caring for them is impacting the lives of their loved ones, or the costs of providing caring are eating into life savings intended for future generations, whether pressure comes from without or within, it is still coercive. When repeatedly challenged in a major media interview this week, one of the Bill’s key sponsors was totally unable to offer an answer to how medical staff could ensure a decision was not being made under pressure. If even a tiny proportion of those whose lives were ended had been coerced, the Bill is fatally flawed.

Secondly, evidence from the small number of states and countries that have passed some similar form of legislation overwhelmingly demonstrates that whatever limitations on eligibility are set, it only takes a few years for the law to be amended to allow a far wider category of deaths to be authorised, or for loopholes to be found, and left unplugged, with the same result. Nowhere have checks and balances, however carefully legislated, survived contact with the real world.

Third, I give weight to the fact that many people living fulfilled lives despite disabilities, see the Bill as deeply threatening. Crucially, it breaks the principle that all human lives are of huge (most would say equal) value. Once that dam is breached it is only a short step towards saying that some human lives are more costly than they are worth, and reducing funding for care packages accordingly.

None of us want to see loved ones, or anyone, suffering in prolonged agony with a desperately degraded and undignified quality of life. Yet if that is the question, which many proponents of the Bill suggest, then surely, as the Secretary of State for Health has said, the answer is better provision of care, in our hospitals, hospices and homes. It’s not leaving them to suffer so much that they plead to be helped to die.