What was the most emotion you saw displayed by anyone, on either side, during the Brexit debate? One could hardly pass a day during that time without encountering bitter wailing and gnashing of teeth, raging jeremiads, flag waving, flag burning, threats to tear up passports, intemperate accusations of barbarism and betrayal, incontinent outpourings of exultation or black despair.

Such emotion, though, was understandable. The whole question touched on the deepest matters of identity, the meaning of Britishness and Englishness, and also fundamental questions of what principles we should live by and be governed.

We are, however, presently undergoing a change which is far more profound than Brexit, and which is even more closely connected to these essential questions of identity and guiding principles. Yet, this elemental alteration in our national life is taking place with scarcely a frisson of notice.

The recent release of the 2021 census figures showed that fewer than 50 percent of people in England and Wales profess Christianity. This is the first time such a state of affairs has been seen since the formation of England as a kingdom. However, there has hardly been any reaction, either from the government, the Church of England, or even in terms of public debate. The Harry and Meghan Netflix documentary has occupied far more column inches than the deliquescence of one of the nation’s most ancient institutions.

There is, of course, a spiritual impact on every person in England from this change. But one effect of the decline of Christianity which must be considered exerts itself on English public life.

The ebbing away of belief has gone hand in hand with an evaporation of widespread popular knowledge of Christian ideas and values. Yet, it is these Christian ideas and values which underpin huge parts of English national life and institutions. The disappearance of public knowledge of these underlying Christian ideas makes it increasingly difficult for many people to understand English history and institutions. It also makes these institutions vulnerable to change — often for the worse.

Take, as just one example, the monarchy, and its relationship to law and the citizen. Christianity may have been prominent in the Queen’s funeral, and will again be so in the King’s coronation next year. However, few will have realised just how intrinsic Christianity is to the monarchy’s nature and evolution — and thus that of the executive in English modern government.

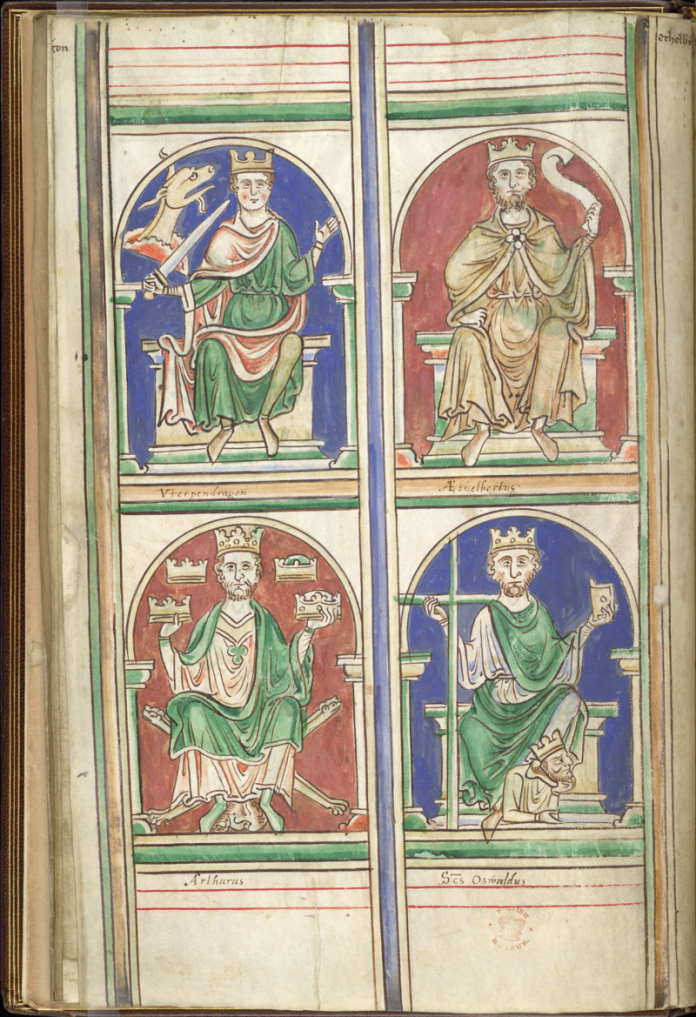

The earliest kings in the territories of England after the Saxon invasions were little more than warlords of marauding bands. Their authority sprang from brute power. It was only with the influence of Christian thought that kingship in these regions developed into something we would recognise. The Venerable Bede, writing in the early eighth century, propagated theories of kingship that were to be highly influential. These theories were grounded in Christian doctrine.

Kings, argued Bede, had to follow the example of Christ, the paradigm of a “moral and just ruler”. The foundation of kingship was morality and sanctity. It was a vocation that needed training and constant self-examination. A good king, Bede writes, has the Christian attributes of prudence, fortitude, justice and temperance. The relationship between a king and his people should echo that of a bishop taking care of their flock, again after the manner of Christ.

A leading example of a good king, said Bede, was Oswald of Northumbria. One instance of his virtuous behaviour was him distributing not just his own food to a crowd of poor beggars on Easter Sunday, but also the silver platter from which he was going to eat it. “Though raised to the height of regal power,” wrote Bede, King Oswald “was always humble, kind, and generous to the poor and to strangers.”

Read it all in The Critic