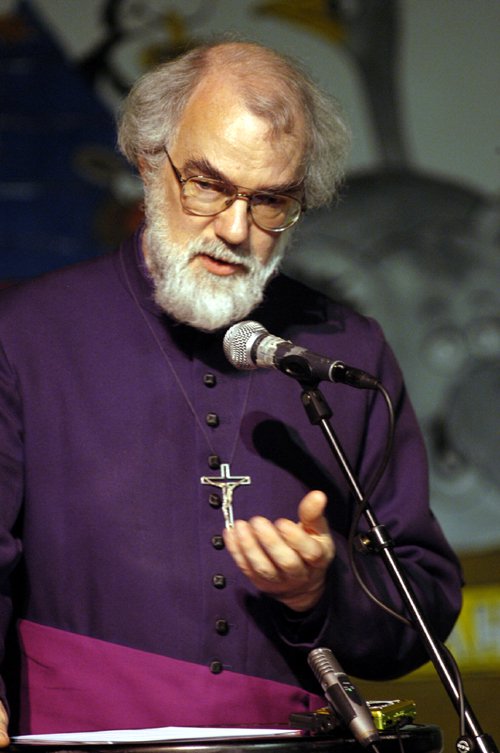

It has been thirteen years since Rowan Williams stepped down as Archbishop of Canterbury and head of the Anglican Communion. Yet he still feels compelled to intervene in national debates. He has now turned his attention to the thorny issue of migration in the opinion pages of The Guardian, no less. It turns out to be exactly the right venue for the piece, though it also confirms that Williams is no longer well placed to pronounce on an issue as wide-ranging, contested, and materially consequential as this.

One might expect Williams to be well-placed to comment — drawing on his impressive cultural as well as theological knowledge. Alas, erudition can be compatible with intellectual cowardice and complacency. Indeed, cultural references can mask a lack of analytical acuteness.

Williams complains that “we are repeatedly sold a painfully two-dimensional picture of the motivations of those seeking shelter in Britain”. Yet it is he who proceeds to paint in the broadest, most reductive strokes.

The article constructs a straw-man interlocutor against whom easy moral victories can be claimed. Williams implies that critics of current migration levels wish to halt migration altogether, and that they deny migrants any role in Britain’s history. In reality, most concern on what Williams snootily dismisses as “the right” centres on scale, speed, and governance. But this paper tiger allows him to demolish a phantastic position rather than engage with an argument that actually exists.

The veteran theologian then commits an egregious category error, treating elite work-based mobility and mass migration as if they were broadly comparable phenomena. The implication is that those objecting to an influx numbering in the millions are really objecting to the small number of highly skilled, highly valued migrants whom every society, at every point in history, has actively sought out. By invoking exceptional figures — artists, composers, Gothic master masons for goodness’ sake — the article conflates small-scale, skilled, invited movement within shared civilisational frameworks with contemporary large-scale, rapid, often low-wage migration. These are not variations of the same thing; they are phenomena with entirely different social causes and consequences.

True to his lifelong habit of airily contemplating the heavenly plains, Williams substitutes aesthetic and moral reflection for everyday material reality. Cultural enrichment and creativity are offered as answers to concrete problems such as housing pressure, social cohesion, labour markets, and public services. Symbolic benefit is substituted for actual cost. It may suit Williams’s lifestyle and self-image to drift between art installations and elite colloquia celebrating “migrant voices”, but such concerns are not foremost in the minds of people whose towns have been transformed beyond recognition. They cannot get a GP appointment, never mind secure decent, affordable housing.

Of course, the history of Christian thought is full of privileged men who withdrew from worldly cares to contemplate the state of their souls. Shortly after his conversion, Augustine of Hippo retreated to his patron Verecundus’ villa at Cassiciacum, just outside Milan, where a small, educated circle engaged in the colloquies that became the Cassiciacum dialogues. But Augustine was acutely aware of the conditions that made this possible. He reflected explicitly on that which he later names Christianae vitae otium — the leisure of Christian life. The saint critiqued pride as a barrier to wisdom and showed gratitude for the patronage that bought him time to think. Writing later, in his Retractationes, he criticised the youthful works for their overly classical tone. This combination of privilege, self-awareness, and accumulated humility is precisely what is missing from Williams’s serene invocations of art and colloquium culture.

Williams’s article might still be indulged as the unaware affectation of a long-time ivory tower resident, were it not for the fact that Williams then adds insult to injury by invoking grooming gangs. Read it all in The Critic