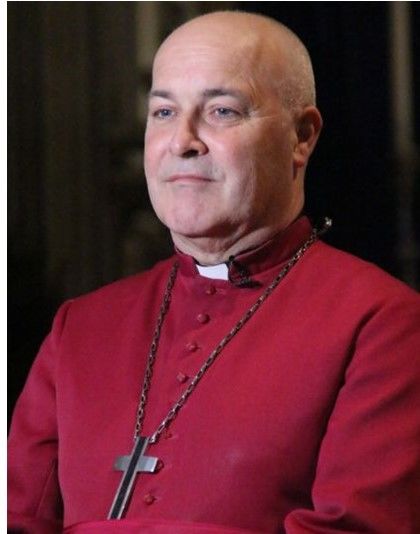

Writing in today’s Credo column in The Times, Archbishop Stephen explores how the Lord’s Prayer can teach us how to pray and how to live. The article follows in full…

What is prayer for? Listening to prayer being offered in Church, you’d be forgiven for thinking the idea is to change God’s mind. Or maybe let God know what’s going on down here.

But that can’t be right.

Just before he teaches his disciples, the prayer we call, the Lord’s Prayer, Jesus says that, God ‘knows what you need before you ask him.’ In which case, ‘Why pray at all?’ Or to ask the question again: ‘What is prayer for?’

Well, perhaps it’s to change our mind?

The Lord’s Prayer is an education in desire. God may know what we need. But we don’t. It teaches us ‘what to want’ and ‘how to live’, as well as what to pray for.

A great Anglican theologian of the last century, Austin Farrah, described the Lord’s Prayer as three hearty praises followed by three humble petitions.

First we learn that God is like a loving parent, the one Jesus calls ‘Father’ and that God’s name and God’s nature is holy.

Secondly, we learn that God’s will is to be followed and established in our lives and in the life of the world.

Thirdly we learn that God’s kingdom, which means God’s rule and God’s commonwealth, is the way of peace and justice the world must seek. In this way, earth becomes like heaven and heaven comes down to earth.

All this Jesus lays out for us, resetting the compass of the heart in these profound opening petitions –

Our Father who art in heaven,

hallowed to be thy name.

Thy kingdom come, thy will be done

on earth as it is in heaven.

Then we find out what to ask for.

Firstly, enough.

Give us our daily bread means, ‘Give me what is sufficient for today.’

In the midst of the heat and horror of a climate crisis is there anything more important for the human race to learn? These words are a guard against envy and avarice, challenging those economic conventions that think everything must always be growing and we must always want more. Not only this; by preventing ourselves from always wanting more, we may be become much better at sharing what we have.

Secondly, reconciliation. We need to be forgiven. We all know this, even if we never acknowledge it. And even though we live in a society where most of us want to be understood, rather than forgiven, the fact is that most of us fall short of our own standards, let alone God’s. Moreover being known and understood and still being forgiven is liberating good news, probably the greatest gift of the Christian faith and the reason Christ came to reconcile us to God and to each other. It is the meaning of his cross and resurrection.

But this petition carries a condition. If we receive this mercy, then we must be merciful to others too. This is hard, especially as many of us have been damaged, exploited and abused by others. Nevertheless, it is the only way of breaking the cycle of vengeance that convulses the world, breaking so many human relationships, whether it is between nations, countries, communities, families, or friends.

Thirdly, deliverance. We ask that God will be alongside us in times of temptation, darkness, and fear; the Good Shepherd walking with us through the valley of the shadow of death.

We pray –

Give us today our daily bread,

forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us,

lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.

All this beauty and challenge is contained in the Lord’s prayer – and in less than 70 words.

At a recent meeting of bishops in the Church of England we were addressed on Zoom by a young climate activist from Uganda, one of those places in the world where the debilitating affects of the climate emergency are felt most keenly. She was asked about where she found her vision and resolve. She replied by speaking about her Christian faith, the narrative of hopeful change that faith declares, and the life of prayer. In prayer, she said, ‘We envision a world that we cannot see with our eyes.’

Prayer is for God. We are God’s children and we offer God our praise and adoration. We acknowledge God’s sovereignty. We seek God’s way. We discover God’s vision.

Prayer is for us and for others. We are taught what to want. We recognise our belonging to each other. The opening word of the Lord’s Prayer says it all: ‘Ours.’

Not my God. Not your God. Ours. We belong to each other, and when we pray we enter into community with God and with each other. We bring to God our praise and our need. We envision a new and better future.

Prayer is for the world.