My Lords, I join in the tributes to the noble Lord, Lord Ahmad, for his opening and his many distinguished years of service—may he continue in his current position—and to the energy that the noble Lord, Lord Cameron, as Secretary of State, has brought to the present process and this debate.

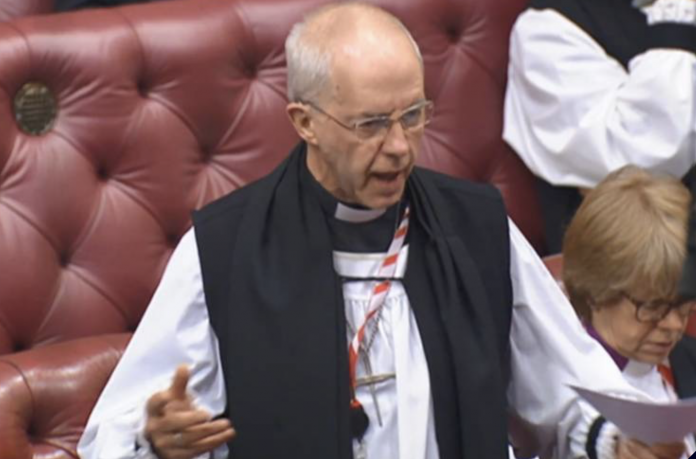

I want to focus, as the noble Baroness, Lady Smith of Newnham, did, on the means rather than the end. Like many noble Lords here, I was in Ukraine three weeks ago—for about a week, in my case—in Kyiv and Odesa. I was there, coincidentally, at the same time as the head of the European foreign service, and we managed, with some of his staff, accidentally to be in the same bomb shelter at the same time, which gives one an opportunity to talk to people. One of the things that came across was the determination of Europe to protect Ukraine from defeat—to support it. However, in conversations with senior politicians in Ukraine, as well as the most senior religious leaders in that very religious country, the question they put was not just what the West intends and what the UK intends—their warm words about the UK were very striking—but what were the means to those ends. You do not win wars by good intentions.

I will not go further on that except to say that the integrated review and the refreshed integrated review talk extensively about ends, but they do not talk at all, or not very much, about means. This is the question that has to be put to government but will be much better handled by the noble Lords and noble and gallant Lords, with infinitely more expertise than me, who are here today.

Moving on from that, I want to talk about something that is a major focus, and has been for many years, in the Anglican Communion. I remind noble Lords that the average Anglican is a woman in her 30s in sub-Saharan Africa, on less than $4 a day, with a 50:50 chance of being in a place of conflict or persecution. The question of avoiding war and making peace applies not only, obviously, in Ukraine and Gaza but, according to the UN’s recent figures, in at least 52 other places around the world. Over the last 10 years, in the 165 countries in which we have Anglican churches, divided into 42 provinces, I have visited all those provinces. I have spent much of that time with people involved in conflicts, seeking to build them up, whether it is in northern Mozambique with training from the UN or other places. It is very striking that the impact of peace- building is not only a primary command of Christ in the Bible—

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God”—

but fundamental to the national interests of this country.

Our leadership, historically and today, in areas of conflict brings us enormous distinction, at huge cost. Our leadership in peacebuilding is something we have the capacity to do: it is hard won and brings long-term prosperity and opportunity. Peace brings development; development brings trade; trade is to our advantage and brings more development. Our soft power assets in this country are enormous, especially when combined with the hard power within our Armed Forces to contribute to the necessary tough side of peacemaking.

We see with Gaza and the horrendous events I saw within a very few days of 7 October—I was in east Jerusalem—the terrible human impact and the almost impossible task of bringing peace in the midst of the sound of the guns. Once the guns begin, peacemaking becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The Foreign Office has an excellent unit, pithily named—I am sorry to have to reach for my notes as I can never get this right; I am sure the Secretary of State could whip it off—the negotiations and peace processes team in the Office for Conflict, Stabilisation and Mediation. I will call it peacemaking for short. It is staffed, like the whole Foreign Office and our brilliant Diplomatic Service, with people of courage, determination, huge experience and great wisdom—small in number and with very little money.

If we are to talk about the use of aid, as the noble Baroness, Lady Smith of Basildon, did so effectively, we must look at where that aid is best used. Putting it properly to the service of peace has a far higher return than any other possible use of it. It saves money on fighting wars and on diplomatic intervention at a time when diplomatic intervention is virtually vain.

This debate will cover so many areas and has so many wise Members of this House participating that I do not wish to go on any longer. I simply hope that the Foreign Secretary, when summing up, will speak about peacemaking. In the refreshed integrated review, the word “reconciliation” does not appear and, when I did a search, “peace” appeared four times in 114 pages. I may be wrong; it may have gone up and I did not notice. Two of those references are in the context of nuclear war.

Will the Government enhance the work of the peacemakers in the Foreign Office? Will they encourage working with the third sector and local groups? Will they bring in the coalitions—for instance, in the south Caucasus and other areas that we forget so easily—which will mean that we in the West are not only resilient, united, determined and courageous but making peace in a way that opens a future for the country and for ourselves?