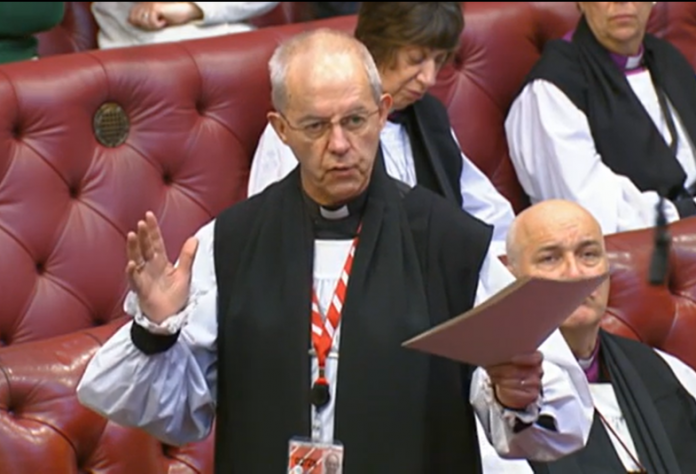

My Lords. I want to start by thanking the usual channels for allowing me to hold this debate today. I am very grateful to all Noble Lords who have come today to participate in the debate or just to be here for the debate. On these benches, we do not take it for granted in any way at all that we have this remarkable privilege of having a debate roughly once a year and it is a great honour to be allowed to do so.

Families really matter. It’s obvious we know that but we forget sometimes why. They are the fundamental building blocks for a flourishing society. This was both the motivation for and the conclusion of the Archbishops’ (plural) Families and Households Commission. I pay tribute to the Commission’s Members who worked for over two years on this, and particularly its Chair, Professor Janet Walker, and all those who took part and gave evidence to the Commission.

It was the final of a series of Commissions, which grew out of a book I wrote in 2018 called Reimagining Britain. The book encouraged us to reimagine a society which is dedicated to the flourishing of the common good, of people and communities. A commission on housing, church, and community reported in 2021, and the Reimagining Care Commission reported at the start of this year.

For as long as human beings have existed, we’ve formed families and households. Families were the birthplace of society itself, and states followed, they are a later creation. Families are the source of flourishing for so many. At their best they are the place of belonging and security, of growth, care, healing, and reconciliation, of training in being a citizen.

They are where we learn to love and to be loved, to forgive and to be forgiven. They are where we learn about trust, respect, commitment, and values, and learn to be safe and confident in our identity.

But we know that families come in all shapes and sizes, in all different societies, and that the shape of the family has changed enormously in our lifetimes. They’re not simply nuclear. My own childhood was messy due to the alcohol addiction of my parents. And a few years ago, I discovered like many people that the father I’d grown up with was not my biological father.

Those who do not grow up with a stable, immediate family themselves, as I did not, often find hope and comfort and healing from being welcomed into and supported by other loving families as I was, or extended families. In my case, that included my grandmother, who cared for me in the times when my parents could not. For others, it’s an aunt, an uncle, Godparents or a loving neighbour.

Households and families, and I shall call them families for short throughout this speech, come in so many shapes and sizes. Those who are single, deliberately or by circumstance, also contribute greatly to households and families through friendship networks, and are usually part of extended forms of household.

Our families and households grow, adapt and age with us. We see the wonder of familiarity and change, the promise of renewal. If we have children or siblings, we are given the gift of viewing life at both ends as both son and father, granddaughter and grandmother, nephew and uncle.

The Commission expressed brilliantly the opportunity we have, to reimagine a society in which all families, all families of all shapes and loving relationships are valued and strengthened. I know my Right Reverend friend, the Bishop of Durham will speak more about the Commission’s focus on valuing all relationships, including those of people who are single.

But family must not be idolised. While it is very often the greatest source of contentment and hope, it can also be for many a cause of despair, unhappiness and trauma. The place where our human imperfections – which we know as sin – give way to harmful and destructive behaviours. We all know the statistics on domestic abuse and neglect – the NSPCC, estimate that around half a million children suffer abuse in the UK each year and the Office of National Statistics found that around 5% of adults had experienced abuse in the year ending March 2022, and about 80%, somewhere around that, found abuse happens within households and families.

And in the Bible family life is messy – our complex relationships become part of the divine story of God, from Cain and Abel, to Abraham to Isaac to Jacob’s family, to the beautiful story of Ruth and especially to the Holy family of Jesus.

So family matters. But what is it that defines families and makes them so crucial for our wellbeing and for that of our society? And the answer is, and it sounds again, banal, but I’ll unpack it.

The bonds of love.

Oh, yes, of course it is, what else might it be? Well, it’s often forgotten. Throughout the Commission’s work they found that in the evidence they had from all places within and outside Christian faith or any other faith. Love was the word most associated with family life. Hence the title of the report. They said,

‘love is undoubtedly the essential characteristic of supportive family life, which knows no boundaries and which is expected to endure through the best and worst of times.’

But what do we mean by love? What we are not speaking of, is an emotional feeling. We mean, and the report means, a deep sacrificial love – which is at the heart of the Christian story. For God so loved the world that He sent His Son Jesus Christ, both for our salvation as we believe as Christians, but also to model a radical new way of relating to one another which is self-giving love, without expectation of return.

And love in the Bible is described in the most practical way.

Here’s a verse that almost everyone knows:

‘Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonour others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.’

It’s a passage from 1 Corinthians chapter 13. It’s often read out of weddings but has application far beyond.

In my mind’s eye I see a journey that my wife and I made late last year, where we stopped off at a service station for a bite to eat. And there was a very elderly couple, both finding extreme problems with mobility, married to each other, and they were supporting each other as they made their slow and painful way back to their vehicle. Nothing very dramatic, you might say, but it was a beautiful picture of love. Not the love we hear of so much in the novels. It was a resilient, enduring, sacrificing, self-giving love that is the biblical position of love. So it’s not just for the benefit of ourselves or our families, but for others. For sacrificial love develops in us the capacity to love and serve without self-interest.

The Children’s Commissioner has described ‘a protective effect of the family’: family has the power to support its members through life’s challenges. Family at its best is the first port of call in a crisis, and the place we can share both life’s joys and sorrows with others who care for us. A colleague of mine is caring for a family who have just lost their second child to cancer. A young boy of 11 who died two weeks ago and the wider family has gathered round and brings strength to these people who have suffered more than most of us can imagine, even those of us who are part of that rare and unpleasant club that has lost one child.

And that resilience that family brings is especially true for children. Family is the best place for children to grow up and develop resilience. The evidence of the commission, this is the evidence, it’s not just a vague thought, is living with loving birth parents is best where possible and when it is not, the state has an important role to play in ensuring that children can be integrated into other loving families which are stable and committed to one another. Stable and committed. That’s not a question of sexuality.

The commission found:

‘there is now scientific consensus that the period from conception to age five is critical in providing the foundation for future physical and mental health, as well as overall wellbeing and productivity.’

The Royal Foundation Centre for Early Childhood, such an extraordinary foundation doing such remarkable work. In 2021 the Government presented a vision and this came partly out of their work for the first 1,001 days through pregnancy to the age of two, when the building blocks for lifelong emotional and physical health are laid. There is evidence that mothers and fathers played the crucial role in these early years.

The protective effect of families is particularly pertinent, given the extraordinary rise of mental health challenges visible in both children and adults. The Church of England Children’s Society concluded in their Good Childhood Report of 2021, an annual production which I commend very strongly to your Nobel Lordships. They said:

‘the continuing downward trajectory of children’s happiness with life as a whole. And other important indicators suggest the UK is struggling to create conditions in which children can thrive’

The Commission’s goal is for all of us as individuals, communities, Government and the Church to put families at the very centre of all we do. So how can we enable bonds of love to flourish within families and households? Exhortation is useful, practical aid is essential. And that comes especially through basic needs like good housing, social care, education, health care, and nutrition. These are moral duties, not just economic calculations. But to what extent should this be the responsibility of Government?

As I said, the family predates society. Government may be useful or harmful to families, but stable families are indispensable to Government and society. We literally cannot exist as a state without them. And not only because it will cost too much.

Governments must seek to support the intermediate institutions, which are the only way of delivering effective family support at the local level. Those bodies and groups which sit between the family or the individual in the state, and have for much of history done the heavy lifting and care for one another’s wellbeing and promoting the flourishing of society. All our Commission’s made recommendations to the church and for other bodies in society, not simply to Government, and that applies to this one.

William Beveridge is often referred to as a father of the welfare state saw the crucial importance of voluntary institutions in his 1942 report, where he identified the five giants to be conquered, he wrote,

‘The State, in organising Social Security, should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility; in establishing a national minimum it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than the minimum for himself and his family.’

And in 1948 Beveridge wrote in his less remembered and much ignored further up Voluntary Action – it is gendered language, but it’s 1948 –

‘how much all men owe to Voluntary Action for public purposes in the past’, and suggested ‘how Voluntary Action can be kept vigorous and abundant in the future.’

There is a crucial role for individuals, churches and other charities and institutions to play in putting families first. The ideal is for the state to act in such a way as to create a positive reinforcing loop, a force multiplier, with the actions of individuals, intermediate institutions and families themselves. To make space for families, neighbours and communities to care for one another.

And I will focus in this final bit of the speech on two areas where the Government through its legislation, regulations and example can promote the flourishing of families and households.

The first is ensuring that whenever a policy is created in any Government department, its impact on families and households is considered and acted upon. Does it enable the bonds of love within the family of the household to flourish? Does it support and strengthen relationships?

This week, we hear that many people in this country will be prevented from living together with their spouse, child or children, elderly parents, as a result of a big increase in the minimum income requirement for family visas. The Government is rightly concerned with bringing down illegal migration figures and I’m not – you’ll be relieved to know – going into the politics of that – but there is a cost to be paid in terms of the negative impact this will have on marriage and family relationships. For those who live and work and contribute to our life together, particularly in social care.

The family test already exists. It was introduced by the Noble Lord, Lord Cameron’s Government in 2014 and seeks through five questions to introduce a family and household perspective into the policymaking process of every department. I know that DWP are currently conducting an internal review to look at ways to strengthen the test – that’s welcome.

The family test should be on the front of every bill. It should have practical implications for policy, from Treasury spending decisions to the impact of sentencing in the criminal justice system on which I look forward to hearing more from my Right Reverend friend, the Bishop of Gloucester.

And so the main thing I urge Government is to consider giving the family test, and with the support of the opposition, greater teeth to support its implementation across Government departments. Will they require completion and publication of the assessments to increase transparency and learning across Government? Will they also consider reviewing the questions asked within the test, to focus more on children, and on all aspects of wellbeing – emotional, social, spiritual and material? Let me remind you what I said a few minutes ago. The state is useful for the family, but the family is indispensable to the state. A lack of strong families undermines our whole society. Government needs families to work, they must not set a series of hurdles for them to jump over. Another key consideration with regard to policy is whether it is family proof, is it flexible enough to accommodate the different ways in which family lives?

One example is the two child limit on benefits. I pay tribute to the tireless work of the Bishop of Durham for his campaigning in this area. The End Child Poverty campaign estimates that removing the two child limit would lift a quarter of a million children out of poverty. The moral case is beyond any question. Yet, the unfair penalty applied to additional children affects their educational outcomes, their mental and physical health, their likelihood to require public support from public services later on. It is not a good policy. Will the Government and the opposition, should they become the Government at some point, consider removing the two child limit and addressing other systems and policy choices which keep families in poverty?

Finally, supporting families, housing and social care. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s recent report on destitution revealed that around 3.8 million people experienced destitution, total absence of resources, not just poverty, including around 1 million children in 2022. That was two and a half times the number in 2017 and tripled the number of children.

Our social security system designed by Beveridge to reach everyone is simply staggering under the burden of trying to meet the needs. The situation is grave, especially for those who are disabled.

In addition, our Housing Commission highlighted a chronic shortage of social and affordable housing. Good housing, sustainable, safe, stable, sociable and satisfying is necessary. They integrate in supporting families. The Reimagining Care Commission called for a National Care Covenant to clarify the responsibilities of everyone, Government and others in care and support.

Putting families first requires a long term approach and so I urge all parties as we move towards an election year, to place flourishing families and households as a key objective within their manifestos at the next election and to recognise their responsibility and self-interest for the wellbeing of adults and children alike, for transforming the way our society operates.

Herbert’s famous poem ‘Love bade me welcome’ speaks of the sacrificial love of Christ who welcomed him in when he did not deserve it. Flourishing families are the place where we experience similar love and welcome.

Love matters, my Lords. Families matter. Relationships matter. I urge us all to seek ways to support their flourishing.

I beg to move.